An outlandish jumble of cults, cannibalism, and colonial violence

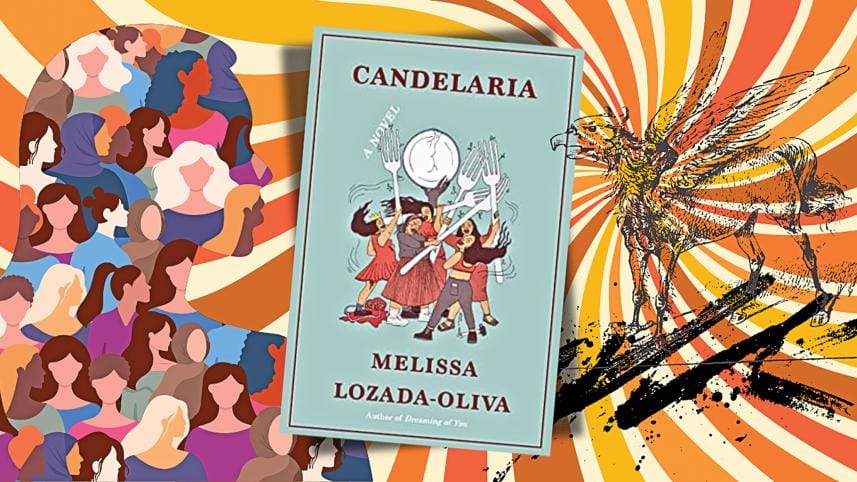

Melissa Lozada-Oliva takes us on a bumpy apocalyptic horror ride in her debut novel Candelaria. Spanning across three generations of women, the novel ushers together an unsettled past and an even more bizarre present. Candelaria is the titular character in this story—there are two of them and they have more similarities than just their shared name.

The novel initially appears to be dealing with abuse and generational trauma. But slowly, it emerges as an apocalyptic horror story filled with giants, dead people and a certain stone. The plot is more than a little nebulous. Cultish incidents happen after Candy aka Candelaria, the youngest granddaughter becoming pregnant after a one-night stand with Fernando, Bianca's ex boyfriend who may or may not have been dead at that moment. While being pregnant, Candy starts engaging in strange activities such as eating her co-worker Jennie and boyfriend, Garfield.

There are striking parallels between the ongoing political topography and the themes explored in Candelaria. Lozada-Oliva beautifully uses cannibalism as an artistic motif here. "This world has made it so that we are terminally the consumer, and without thinking, all of a sudden, we have become the consumed." This comes across as a translucent critique of late stage capitalism. The cult's obsession with Candy's pregnancy and inhibiting her from getting an abortion is a sharp parallel to the political rhetoric of recent anti-abortion laws in the US. The writer cleverly compared the cult with the conservative politics regarding women's bodily rights. It would not be too radical to imply that motherhood can also be a cult. And the pro-life rhetoric of the right reflects specially in the activities of the cult leader, Maria. In the novel, it talks of a stone called "The Mother". And according to Maria, the order of nature can only be restored by birthing babies. In the aftermath of Carmen's (another pregnant woman in the cult) delivery, she is murdered. So would have been Candy's fate if she hadn't managed to escape. The activities and core beliefs of the cult is very much analogous to anthropomorphising nature as women and mothers. And Carmen's death only enforces the rhetoric of pro-life politics.

Ursula K. Le Guin in her utopian science fiction The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (originally published in 1974) reflects on the nature of the relationship between a foetus and the mother. In the book, Takver, the protagonist Shevek's partner, says that pregnant women are "possessed" by their foetuses and it alters their brain chemistry.

Ursula K. Le Guin in her utopian science fiction The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (originally published in 1974) reflects on the nature of the relationship between a foetus and the mother. In the book, Takver, the protagonist Shevek's partner, says that pregnant women are "possessed" by their foetuses and it alters their brain chemistry. The use of the word "possessed" here indicates something demonic which we also notice in Candy transforming to a cannibal when she is with child. She says it is the child who is harboring cannibalistic cravings, making her do such things. It is very much telling how the state and society in general cares more about a fetus than the life of the mother. Candy here, seen as a baby producing machine, very much symbolises the picture of the "mother goddess" who is young, promiscuous, and fecund.

The consumer versus consumed is also a critique of the continued colonisation of Guatemala. Bianca's lack of fluency in Spanish gives her an outsider status in Guatemala. But what's interesting is the Spanish influence in Guatemala is due to Spanish invasion in the early 16th century and if Bianca were to feel more like a native there through only speaking Spanish, she would still be talking in a coloniser's language. Hence, it tells us that colonialism can be reproduced and it can be sustained through a language.

These narratives, whilst carefully crafted, still failed to make me interested in the tumultuous lives of the characters. The prose seemed amateurish and leaves a lot to be desired. The real conflict in the book was the family dynamics and how trauma transcends through generations but it was poorly done and was disconnected with the rest of the plot. The novel doesn't shy away from concocting a complex world but falls massively short in the execution of it. My biggest criticism is that the author failed to make the genre of the book clear to the audience. The conversations between the characters, especially the three sisters, felt inauthentic, as though they were talking to different people altogether, immersed in wholly different conversations; the author also failed to make me care for them as a reader.

The ending especially fell flat considering the amount of buildup regarding the apocalyptic events. At the end we see, their grandmother, Candelaria, being spun around by a "giant wheel with eyes", but Lucia and her daughters seem absolutely unbothered by it and rather talk about whether Zoe will raise Candy's baby. The lack of coherence in the story made for a poor reading experience. Besides, the supernatural and horror parts of the story did not seem to fit into the story seamlessly and had me confused. Whilst it could have been a great addition to the historical horror fiction genre, the book jumped through multiple themes and subplots and ended up being a mess.

Nawshin Flora is a writer and poet based in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments