Veteran journalist Montaser Marai's inspiring words on journalism and Palestine

As much as I enjoy the occasional indulgence in idleness and the luxury of a quiet lie-down, I rarely miss the opportunity to listen to voices I would not ordinarily encounter. This occasion was no different, and I find myself rather pleased with this side of me. A good conversation can take me to different parts of the country, and fortunately, the latest trip required nothing more than showing up on campus.

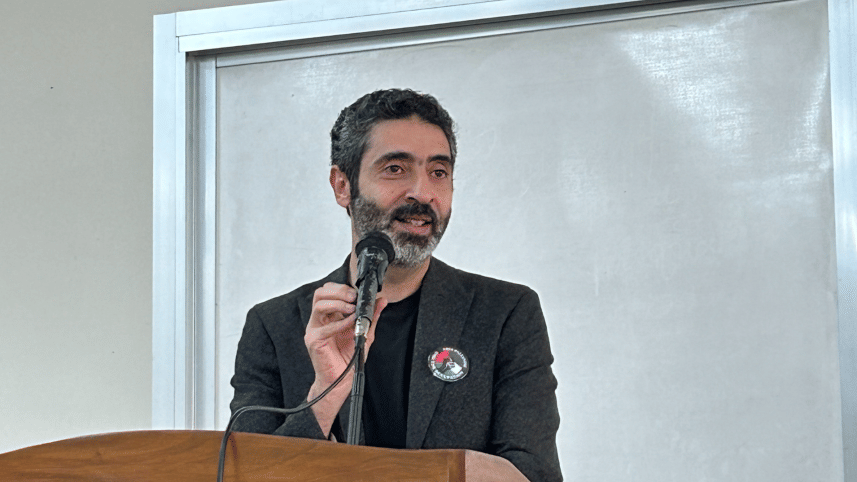

My supervisor, fully aware of my incurable weakness for a good talk, suggested I listen to Montaser Marai, a Palestinian-Jordanian journalist and documentary filmmaker. So, I was delighted beyond belief when I heard that he was going to give a lecture at Dhaka University (DU). Naturally, I arrived on campus a full hour early, because nothing says "eager" like loitering in an empty lecture hall.

Montaser Marai arrived and shook hands with the students. His voice was disarmingly soft as he introduced himself, to such an extent that my ears, long trained on the blaring theatrics of the loud and the louder, found themselves momentarily unprepared.

While sharing his journey he mentioned he joined Al Jazeera's newsroom in 2002. By 2008, he had risen to the position of Head of Production for the Al Jazeera Documentary Channel. During the 2011 Egyptian Revolt, he reported from Tahrir Square and produced several films for the network, capturing the upheaval firsthand.

As a young person, one is likely to be inspired by Marx, Gramsci, or – on more ambitious afternoons – Hegel. Like every undergraduate in the social sciences slogging through political economy, I stumbled into the orbit of Noam Chomsky, that perennial voice saying things the status quo would rather not hear.

Inevitably, this meant watching Montaser Marai's documentary Noam Chomsky: Knowledge and Power, a rite of passage as predictable as overdue library fines.

So, it is natural for Montaser Marai to begin with Gaza – because, he argued, one cannot talk about journalism now without first talking about Gaza. From there, he moved swiftly to the West's persistent blind spots. To me, that immediately placed this lecture in discourse and Edward Said's work on the Western bias.

The problem, he suggested, is not simply bias but a lack of appreciation for ourselves: we translate endlessly, but rarely create. Knowledge, in this arrangement, is always borrowed, never authored. To break this cycle, he insisted, requires a reclamation of language, of culture, of the very authority to narrate our own realities.

He was equally insistent on bridging what he saw as the needless divide between the theoretical and the practical in journalism. One without the other, he said, is incomplete: theory without practice is sterile, practice without theory is rudderless.

What is required is a journalism that speaks to and with the people, rather than allowing others, especially the West, to dictate the terms of our grievances. Journalism, at its most vital, is not about repeating borrowed words. It is about listening to our own voices.

At one point, he drew comparisons between the Arab Spring and Bangladesh's mass uprising. Both, he said, embodied an insistence on self-determination that remains deeply instructive. It was, in fact, this spirit that had brought him here in the first place. Bangladesh, he noted, had shown a rare and public solidarity with Palestine – its people outspoken in ways that inspired him.

From this vantage, he urged a move toward a decolonised media: one that does not wait for permission to tell its stories, but claims ownership of them from the start. While he criticises his own methodologies but the overarching theme was to create solidarity from our shared histories of oppression.

The political economy of it all is, of course, hopelessly convoluted, so tangled that one could lose a career in its footnotes. But history, stubborn as it is, keeps pointing us toward the stories that matter, the ones suppressed yesterday and muffled again today. Bearing witness to the ugly, Marai reminded us, is a necessity; censorship, in contrast, serves no one. His insistence was stark: the images of bloodied Palestinians are interruptions, jolts meant to stop the world in its tracks. That, he argued, is journalism's task, not to comfort, not to flatter, but to show us the truth we would rather not see.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments