In the shadow of July: The parents who waited, worried, and walked together

"I don't think you should be getting involved in this ruckus."

"I am so proud of you; carry on."

"Please be careful; I am worried."

"Do you even know what you are getting yourself into?"

Last July through August, anyone who took to the streets heard versions of these lines over and over again, sometimes in the same breath. Parents, older siblings, aunts and uncles, and some well-meaning neighbours, all participated in the same exchange. Some said it with pride, some with fear, and most with a mix of both.

Between July 15 and August 5 last year, parents across the country held their breaths waiting, worrying, and counting the hours until their children returned home from the protests. Some had their parents' blessing. Others went without it.

We must remember Mahamudur Rahman Saikat, 20-year-old who had completed his HSC exams in 2023 from Government Mohammadpur Model School and College. On July 19, 2024, he was shot in the head in front of the government primary school on Nurjahan Road in Mohammadpur, Dhaka. Since that day, a man, his father, has often been seen standing at that very spot. He stood there in silence.

We must remember Golam Nafiz, a student of Banani Bidyaniketan School and College, killed on August 4, 2024. When Nafiz's father first saw the photograph of his son's lifeless body, he could barely believe it. Still, he made his way to the morgue at Suhrawardy Hospital to claim him—his boy, now gone.

And we must remember Nafisa Hossain Marwa, a 17-year-old HSC examinee. She was killed on August 5, 2024. When the 2024 HSC results were published, her mother, Kulsum Begum, with tears in her eyes, spoke about Nafisa's aspirations of becoming a photographer or a graphic designer.

Hundreds of stories are the same as these three.

Campus reached out to parents to hear about their perspectives. A multitude of responses were collected. Most often when they spoke about their perspectives, fear was palpable.

Hosneara Binte Shahadat, mother of a Dhaka University (DU) student who joined the protests on July 7, 2024, says, "I was extremely worried and often told my daughter not to go out, but she did not listen."

Hosneara spent those days anxiously checking in, waiting for replies, trying to keep her mind steady.

"I see parents of children who were killed last year during this time. I cannot help but feel helpless because only parents can understand how it feels to lose their children," she adds.

Hosneara noted that when students were attacked on the DU campus on July 15, her daughter was present. She says, "I was under immense pressure, wondering whether my daughter will come home safely."

Hosneara mentioned that she was anxious every time her daughter went out. Conversations with other parents revealed similar worries and anxieties.

The worries and anxieties are compounded when the protesters were from marginalised communities. Campus reached out to a parent to a child from a Christian family who wished to remain anonymous; he went on to reflect that in times of political unrest, the marginalised are often turned into convenient tools. That weaponisation, he said, can come at a steep cost. For parents in those communities, the fear is natural.

This natural fear of losing children to a just cause is a common denominator, causing many parents to seek refuge in prayers in silent support and solidarity. Such is a sentiment echoed in the account of Rehnuma*, a mother of two from Dhaka, who says, "It's natural to be concerned as a parent, and initially, I didn't want them to participate, but my eldest son had done so regardless. I tried warning him, but he opened my eyes to the fact that we should all stand up against oppression. Eventually, I resigned myself to praying for the safety of all the children who had taken to the streets, including mine, and for their mothers to have strength."

Rehnuma firmly believes that the protests by students were not only laudable but entirely necessary. "Despite being terrified for my children's safety as they expressed solidarity on social media and physically attended the protests, I believe July was God's way of opening our eyes to the evil that was upon us. I look upon last July as a reminder that we must stay vigilant and stand against injustices."

However, not every parent could find it in themselves to allow their children to take part in the protests out of fear. Mahbub*, a father of three, shared how the sight of tear gas, sound grenades, and bullets around his home made him fear for his family's safety and well-being.

"From July 18 (2024) onwards, I saw goons running around the streets every day with machetes and guns, hunting young people and students," he reminisces. "In addition, dozens of police cars passed by our home every day carrying arrested individuals. That is why I didn't feel safe letting my children out of the house. I even felt afraid at times just going out to buy groceries."

The same level of fear extended to the digital sphere as well, as simply posting in support of the protest was enough to land people in a world of trouble at the time. Mahbub shares, "I did not post anything on social media and even instructed my children not to post anything against the government either. Truth be told, I was afraid of our draconian cyber security laws since we could have been prosecuted at any moment."

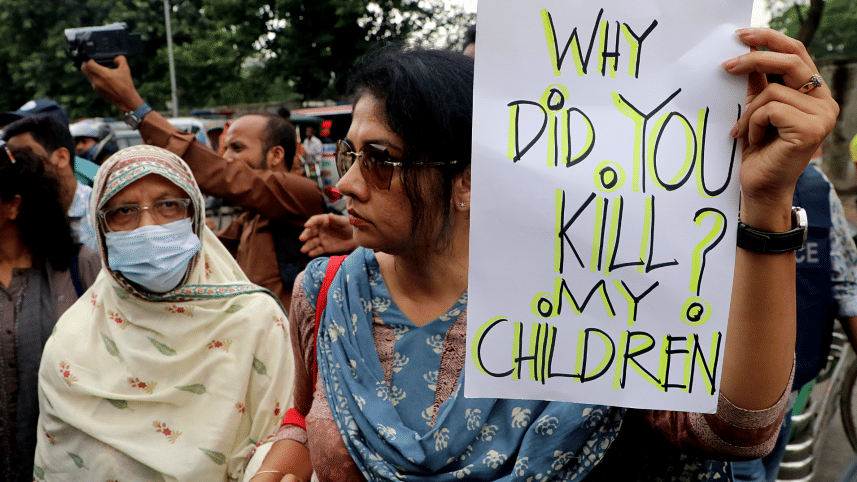

Of course, we cannot speak about parents' contribution and support without paying homage to the brave guardians whose protective instincts brought them to the streets alongside their children. There are innumerable parents who believed they had to keep their children safe without turning a blind eye to the sacrifices of the youth and had stayed true to their conviction.

Ayesha Siddiqua Rina is one such mother who had tagged along with her children alongside her husband. "We were going through an undemocratic time, and I believe the uprising was something we all wanted." she shared. "When my daughter expressed her strong desire to join the protests, and I saw countless kids her age do the same, I realised that this was not a situation where we could sit idly at home. I felt that victory could be within our reach if parents like us expressed solidarity with our children. So, I joined alongside my entire family, and it was truly an experience unlike any other."

Shaheen Akhter, a mother of two, was another parent who overcame any and all fears and braved the frontlines. "When I saw brave young children like Abu Sayed, Mugdho, and Faiyaz being killed, I realised that they could've been my own children," she laments. "That's when I started going to protests with my family. I always made sure to stand in front of everyone else so I could ensure that even if the bullets started flying, they would hit me and not a single child there. You can call it a parent's instinct to want to protect their own children, but everyone at the protests felt like my own kin."

Ayesha continues to express her gratitude towards the sacrifices made by the youth and the parents who had taken to the streets alongside them. Just like Rehnuma*, she believes the uprising was a pivotal chapter, and even if all her expectations of a new Bangladesh hadn't been realised, she holds onto the hope of a better tomorrow.

The parents of martyred students continue to grieve. They believe that their children died for a greater purpose than their own lives. Perhaps this is why their children refused to listen when they begged them to stay at home. Mahmudur's mother watched her son walk out the door, unable to stop him. Her grief almost did not allow her to speak, but she says, "Had I known this calamity was befalling me, I would have confined him to the house."

Every day, these parents sit with the anguish of absence, tears that come unexpectedly. They imagine how their children may have lived. Kulsum Begum, mother of 17-year-old martyred HSC examinee Nafisa Hossain Marwa, who was killed on August 5, 2024, spoke of her daughter's dreams with tears in her eyes. "Nafisa wanted to become a photographer or graphic designer," she shares. "She dreamed of buying land and building a house with her own earnings and mine."

The parents of July 2024 still hope. I took hope that one day they will see a country worthy of their loss. A country that their children believed in.

*The names have been changed upon request for privacy.

References

1. The Daily Star (August 9, 2024). 'I could not believe my eyes.'

2. The Daily Star (August 17, 2024). Father stands silently where Saikat was shot.

3. Prothom Alo (July 27, 2024). Nafiz was still alive on the way to hospital after being shot.

4. Dhaka Tribune (October 15, 2024). HSC result brings tears as family mourns student killed in the July revolution.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments