The cost of crisis: Who will bear it?

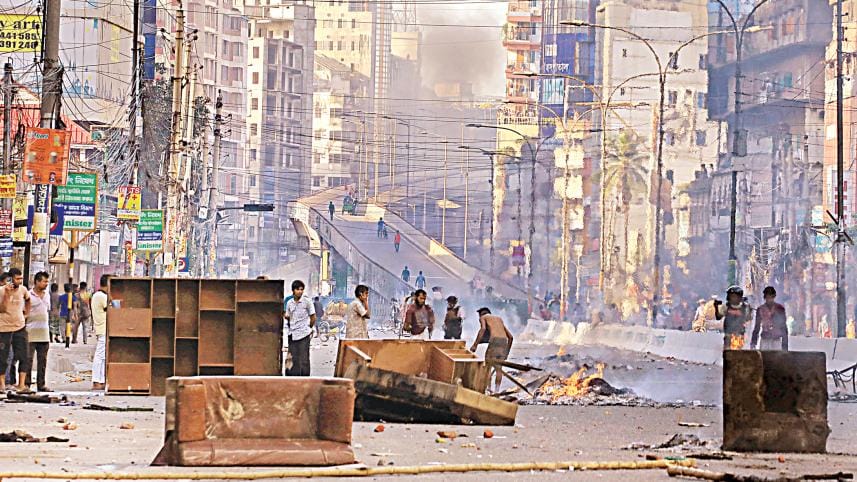

Violence comes with a hefty price tag for the economy. Beyond the immediate death toll mostly in police shootings, the convulsion of violence that gripped Bangladesh in the middle of this month has left a debilitating impact on the economy.

The impact of violence amounts to direct and indirect costs as it disrupts economic activity, increases instability and erodes human productivity.

In Bangladesh, crushing quota protests and subsequent violence were met with a sudden curfew and a crippling internet shutdown.

During the spell of unrest, many lost their lives and many others became disabled while public assets were vandalised or went up in flames in arson attacks.

While the curfew stemmed the tide of violence, it came as another shock to the already fragile economy.

People have been unable to get access to their bank accounts or pre-pay their gas and electricity bills due to the internet outage.

Panic buying has been reported in Dhaka and other major cities, with supermarkets and other stores running low on essential goods.

Many businesses were simply unable to operate, from food delivery services and e-commerce to the nascent outsourcing sector. It also remains to be seen how the internet disruption has affected Bangladesh's garment sector, which accounts for about 85 percent of the country's exports.

Details of the economic damage are still emerging. Export orders may be diverted and inward remittances may slow.

"Some insiders worry that instability will see the country lose orders to competitors elsewhere in the region. The impact of the protests will place further stress on an economy that was already ailing," Pierre Prakash, programme director for Asia at the International Crisis Group, said in a report on July 25.

The Foreign Investors' Chamber of Commerce and Industry estimated that the economic cost of seven days climbed to $10 billion.

The burden of human and economic toll is becoming heavier. But who will bear the cost?

The families of the dead will fend for themselves. Those who were disabled in the mayhem will suffer for the rest of their lives.

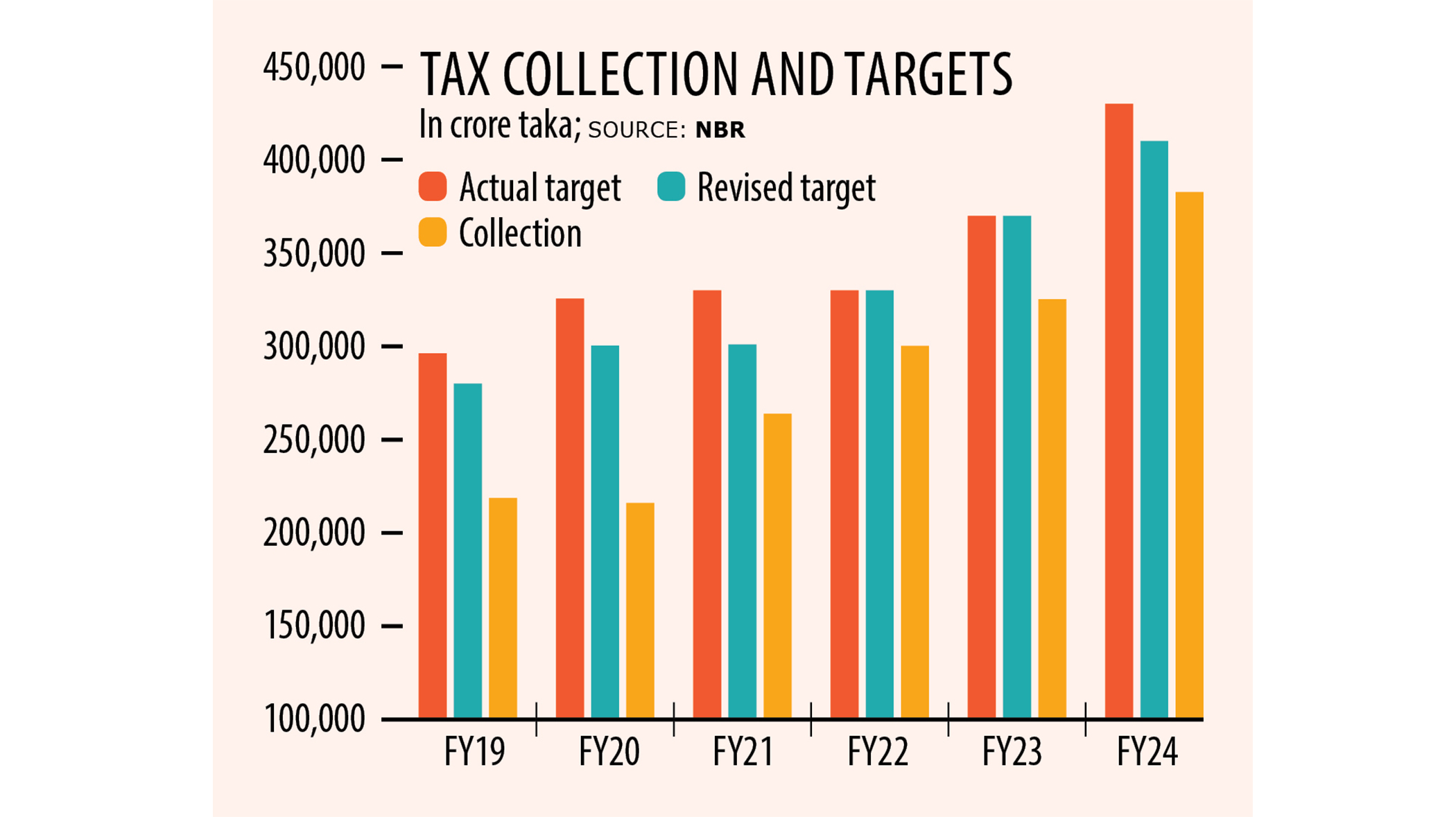

To mend the public assets, the government will use taxpayers' money, which means a massive financial haemorrhage at a time when Bangladesh needs to avoid waste.

The government, hamstrung by the economic crisis, will have to pause development projects, which will take a huge toll on the economy in the future.

Md Shafiqul Islam, the owner of a printing shop, said he has to pay his workers regardless of losses. The man had to close his factory for about six days as violence convulsed the country.

As the protests turned deadly, the poor paid the price by spending more to buy essentials. Consumers were already struggling due to a rising trend of inflation for two years.

All costs of the man-made crisis will be passed down to ordinary people, especially the poor and marginalised groups, said Mustafa K Mujeri, a noted economist.

Historically, these groups are the worst sufferers of any crisis due to their limited coping capacity, said Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development.

"So, the burden of the crisis is hitting them harshly," Mujeri said.

The internet blackout also affected the encashment of inward remittances through banks and mobile financial services, which may put a strain on the country's foreign exchange reserves.

The IT sector is slowly returning to normal after the resumption of the internet, but it is still facing slow internet speeds.

Restaurant owners are staring at mounting losses as they were already struggling to stay afloat after the devastating Bailey Road fire, said Bipu Chowdhury, joint organising secretary of the Bangladesh Restaurant Owners Association.

After some recovery in the five months since the blaze, restaurant sales fell by more than two-thirds in the space of two weeks this month.

Economic gloom has also clouded the garment industry, a time-sensitive sector.

"Any delay in shipments will hurt the sector," said Faruque Hassan, a former president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association.

During the pandemic, companies kept their manufacturing units open, but the unavailability of the internet stalled them. Besides, backward linkages were impacted and the supply chain was seriously disrupted. Some companies faced cancellations of orders and some were forced to send products by air.

Although the crisis now seems to be easing, its impact on exporters will linger for a month, because it has created a huge backlog of unfinished tasks.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments