Most shrimp factories shut as exports from Bangladesh halve in 7 years

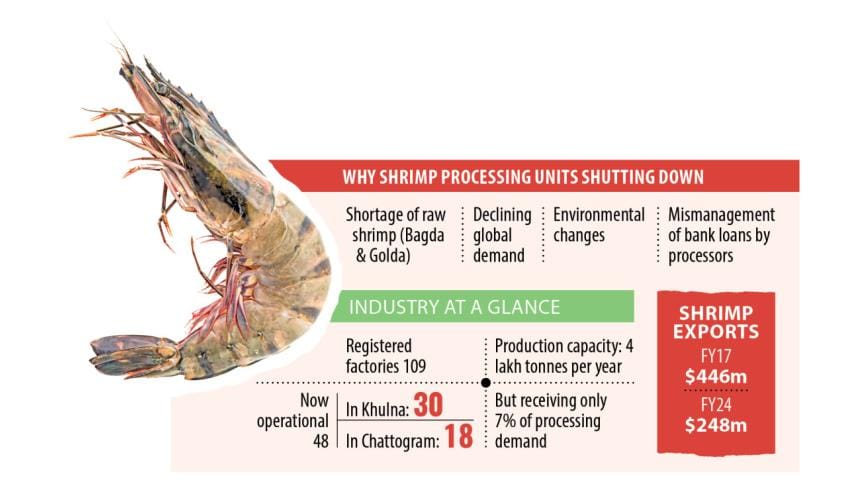

The once-thriving shrimp processing industry is now facing a severe downturn, with processing units shutting down as exports have halved in seven years.

Formerly a major contributor to the country's export earnings and rural employment, the industry is struggling due to a combination of factors, including a shortage of raw materials, declining global demand, environmental changes, financial mismanagement and failure to adapt to changing market conditions.

Cashing in on export subsidies and rising global demand, many shrimp processing units sprang up in the southwestern, southern and southeastern regions in the 1990s, backed by low-cost bank financing.

The industry boom lasted for around a decade, but as global demand for shrimp subsided and incentives fizzled out, production began to falter. Shrinking local supply and the emergence of a domestic prawn market further contributed to the decline.

Currently, out of 109 registered shrimp processing factories, only 30 in Khulna and 18 in Chattogram remain operational, according to the Bangladesh Frozen Foods Exporters Association (BFFEA).

The primary raw materials for shrimp processors are black tiger shrimp (Bagda) and freshwater shrimp (Golda).

According to the BFFEA, these factories have an annual production capacity of around 4 lakh tonnes but are receiving only 7 percent of their required shrimp input.

"This scarcity has already forced many factories to shut down," said Shyamal Das, director of the frozen food association and managing director of MU Sea Food Limited.

"My own company is getting only 25-30 percent of the shrimp it needs, making it impossible to run operations throughout the year," he added.

This supply shortage has led to declining production and factory closures, affecting the livelihoods of around 60 lakh people who directly or indirectly depend on the industry.

Stakeholders in the shrimp processing and export industry cite high bank loan interest rates as a major challenge. Currently, companies in this sector must take loans at 13-14 percent interest rates, much higher than what the rates were in the 90s.

"Between 1995 and 2004, many shrimp processing factory owners invested in the sector. However, they failed to assess the actual availability of shrimp in the market," wrote researcher Gouranga Nandy in his book "Shrimp Profit for Whom".

"Instead, the sector expanded rapidly due to a lack of integrity among entrepreneurs and short-sightedness within the banking sector. Many investors secured large loans by showcasing processing factories but later defaulted on their payments," he added.

While shrimp farming is now categorised as an agricultural activity, processing and export are treated as commercial ventures.

As a result, export-oriented companies face higher interest rates, making it difficult for them to remain competitive in the global market.

DECLINING PRODUCTION

Experts have identified several key factors disrupting the local shrimp production. Those include rising temperatures, fluctuations in water salinity, decreasing depth of shrimp enclosures, poor-quality shrimp larvae, inadequate water supply and drainage, and declining soil and water fertility.

Each of these issues is closely linked to environmental imbalances.

Natural disasters such as Cyclones Aila, Amphan and Yaas have devastated shrimp farms, causing massive stock losses and forcing many farmers to abandon their operations.

Climate change, declining shrimp fry availability and financial mismanagement have left the industry in crisis.

Outdated farming methods have also hindered the industry's ability to adapt.

Despite 50 to 60 years of shrimp cultivation, scientific advancements in farming techniques have been minimal. Farmers in Khulna, Satkhira, Bagerhat and Cox's Bazar struggle with water shortages and increased disease outbreaks in shrimp enclosures.

Besides, shrimp farmers face difficulties accessing bank loans, as financial institutions rarely provide credit for shrimp farming. Consequently, many farmers rely on personal savings or high-interest private loans, further increasing their financial burden.

As a result, some farmers have quit shrimp farming altogether, while in certain areas, local movements have emerged against shrimp cultivation.

IS VANNAMEI SHRIMP THE SOLUTION?

In the global market, black tiger and freshwater shrimp are more expensive than vannamei, or king prawn. Due to its lower cost, higher yield, and compatibility with modern farming techniques, top prawn-exporting countries like India, China and Vietnam cultivate vannamei on a large scale for export.

However, Bangladesh has yet to approve commercial cultivation of vannamei shrimp, although processors and farmers have been pushing for permission for years.

"Traditional Bagda shrimp farming yields 400-500 kilogrammes per hectare, while vannamei shrimp can produce 9,000-10,000 kgs per hectare," said farmer Sutonu Kabiraj, arguing for vannamei farming.

According to the BFFEA, the Department of Fisheries has been reluctant to grant permission for cultivating non-native shrimp due to concerns about its potential impact on biodiversity and the environment.

THE RISE AND FALL OF SHRIMP INVESTORS

In the last decade, around 25 shrimp processing factories have shut down, with closures accelerating after the early 2000s, said S Humayun Kabir, former vice-president of the BFFEA.

He recalled that many investors entered the shrimp processing business suddenly but exited just as quickly due to unsustainable operations.

A walk through the Rupsha area of Khulna bears testimony to the industry's decline. Once home to over 35 shrimp factories, only half remain operational.

Factories including Sobi Sea Food Ltd, Star Sea Food Ltd, Jahanara, Modern, LFPCF, South Field, Cosmos, Shampa, Oriental, Bangladesh Sea Food, Asia Sea Food, Malek Hazi Sea Food, Unique ICE and Food Ltd, Apollo Sea Food Ltd, Shahnewaz Sea Food, and Beximco have ceased production.

Professor Anwarul Kadir, a member of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) in Khulna, said that while environmental factors have played a role, mismanagement and corruption among shrimp exporters have worsened the crisis.

"Some factory owners misused bank loans meant for shrimp production, diverting them to other business ventures and failing to repay them," he said.

"Two-thirds of the factory owners transferred bank loans to other sectors and are now unwilling to repay them. This has significantly contributed to the closure of factories," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments