NPL: Sources of malaise and possible remedies

Excessive volume of non-performing loan (NPL) in the banking sector is a major weakness of the Bangladesh economy. When a loan is sanctioned, it includes a repayment schedule comprising principal and interest amounts. According to Bangladesh bank regulations, a loan becomes non-performing when the borrower fails to pay the scheduled principal and interest amounts for more than 90 days. If the proportion of NPL grows, it reduces the capacity of banks to sanction further loans, their capacity to repay the depositors, and their ability to earn profit. Continuation of large size of NPL may lead to liquidity crisis in the overall banking sector and even failure of banks.

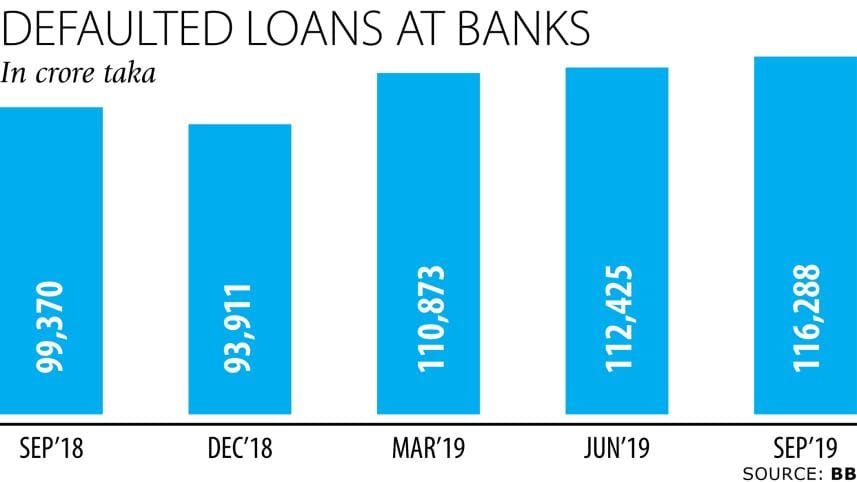

NPL in our banking sector stood at Tk 112,425 crore as of June 2019, which is 19.71 percent higher than the NPL amount at the end of December 2018. Rising NPL is, no doubt, a threat to the stability of the financial health of the country and we need effective remedy to this problem.

The proximate reason behind the high volume of NPLs in Bangladesh is “adverse selection”. The financial institutions (FIs) often end up selecting the wrong borrower and funding the wrong activity. What leads to such adverse selection? A straight-forward summary response to that would be “poor lending practices of the FIs”.

The FIs usually do not have any effective research or business intelligence units to collect, monitor and analyse business information to assess the true potential of diverse business activities under changing local and global economic and policy environments.

There is also very little effort on the part of these institutions to seek out promising entrepreneurs, particularly new ones. Attempts to determine the characteristics of the entrepreneurs through “Know your customer (KYC)” screening are often inadequate. For example, information is collected on the credit status of the borrower from the Credit Information Bureau (CIB) and an unclassified status is considered satisfactory. But questions are rarely asked regarding the number of times the borrower may have rescheduled the loan or created forced loan in the past.

One factor influencing the loan portfolio of the financial institutions is the bandwagon effect. Many borrowers try to set up enterprises with institutional finance influenced by the success of others in particular types of activities. This happened in Bangladesh in the past in the case of power loom, readymade garments, ship breaking, cement etc. and recently such a craze is observed in setting up automated rice mills, brickfields, and hotels and holiday resorts. In the absence of proper evaluation of the key determinants of success in these activities, financial institutions often get carried away by the enthusiasm of the potential borrowers based on others’ success stories. To the extent that market saturation, size of operation, location, varying entrepreneurial traits and a host of other factors may have bearings on the outcome of the investment, financial institutions run the risk of making adverse choices in such cases.

The second shortcoming embedded in the lending process is poor appraisal of the credit proposal. Even when the activity (for investment) and the borrower are selected properly, problems may arise due to faulty estimation of the optimum credit need, which often leads to over-financing, creating scopes for fund diversion, over-invoicing and even money-laundering. Problems happen at the other end as well. Sometimes the size and duration of loan is inadequate and puts the borrower into serious cash flow problems, particularly because of compounding high interest rate. Another aspect of deficient appraisal is faulty assessment of collateral, resulting in under-coverage of the loan or acceptance of collateral of dubious quality.

These instances of system failures and lack of due diligence get compounded when there is collusion between the lender and the borrower or undue pressures are exerted by influential borrowers. In a few extreme cases of collusion or pressure from influential quarters, funds are siphoned off against little or no collateral or against false documents with the intention of money-laundering or diversion of funds to unauthorised uses.

A genuine entrepreneur with a properly designed credit proposal is unlikely to collude with lenders as payoffs involved in such collusion will not be financially worthwhile for the borrower. In contrast, swayed by the bandwagon effect, a large number of overenthusiastic borrowers tend to over-design their credit proposals either in collusion with lenders or through support from influential quarters. If credit proposals with such flawed design dominate the choice set faced by the financial institutions, adverse selection becomes a more likely outcome.

Implementation bottlenecks raise further the menace of NPLs. The most alleged implementation snag seems to be delay in fund disbursement and the corruption associated with it. Other than these aspects of poor lending practices, many genuine cases of business failures, which occur due to personal mishaps, accidents, adverse policy changes, market failures etc. also contribute towards creation of default loans.

But what is the picture regarding recovery of default loan?

The recovery picture does not appear to be very encouraging either. In the cases where the loan is well covered by adequate collateral, recovery efforts are often frustrated by weak and lengthy legal proceedings. During this period the outstanding debt continues to escalate, overshooting the value of the collateral ultimately. Through the legal measures, the loan defaulters not only get legal proceedings against them stayed, they also manage to get court orders to strike out their names from the CIB classified list, which gives them opportunity to indulge in more borrowing.

In the cases where the loan is not properly covered by collateral, the financial institutions are on even weaker grounds to pursue recovery.

Where loan default involves gross irregularities, criminal proceedings are initiated against the offenders who often land in jails. But then the loan recovery process gets completely thrown out of line. As the banks cannot take custody of the assets of the defaulter until the criminal cases are disposed of, the assets are often lost and any hope of bank recovering a significant amount of the loan disappears. An appropriate example is the Hall-Mark case, where one accused died in jail and others are still behind bars, but the prospect of bank recovering the loan is almost nil.

So, how does one get out of this messy NPL situation? What is the remedy?

Well, as they say, “prevention is better than cure”. The first thing that must be done is to ensure that no new loan gets classified. For this, one needs to strengthen lending discipline in the FIs. This will involve intervention at four levels:

First, with strong and independent internal control and compliance (ICC), the FIs must ensure proper KYC and due diligence to satisfactorily evaluate a loan proposal and correctly determine market potential, value of the collateral and optimum credit needs.

Second, the board of directors must ensure that management has satisfactorily resolved all issues flagged by the ICC. Third, selection and appointment of board members should be done on the basis of strict objective criteria and there should be a mechanism in place to monitor the performance of the board members. Fourth, there is a need to strengthen the supervisory capability of the Bangladesh Bank.

For improvements on the recovery front, necessary legal reforms to strengthen and expedite the legal process should be undertaken immediately. Two measures can bring about significant immediate improvements in the situation: loan defaulters should be required to pay a certain percentage of their outstanding debt before they seek stay order on legal proceedings against them, and a dedicated bench should be set up at the high court to dispose of loan-related writ cases.

Effective Bankruptcy Act and Asset Management Company should be put in place as alternative NPL resolution mechanism, in particular to deal with default cases under-covered by collateral and those involving influential borrowers.

Finally, for a large proportion of cases, where the default is due to genuine business failure or fund disbursement delays by the bank, the existing rescheduling facility needs to be made more accommodative.

The author is a senior research fellow of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments