FDI’s hidden crisis: Where is the new money?

A 19.13 percent rise in foreign direct investment (FDI) in Bangladesh for fiscal year 2024-25 may seem worth celebrating at first glance. The Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) reported that net FDI reached $1.69 billion, up from $1.42 billion the year before—a figure that might suggest growing investor confidence.

But the figure is less than one-fourth of what Bangladesh needs. The country requires at least $8 billion in FDI annually to boost GDP growth by one percentage point. The Eighth Five-Year Plan had aimed to raise FDI inflows to 3 percent of GDP, but they have remained below 1 percent each year.

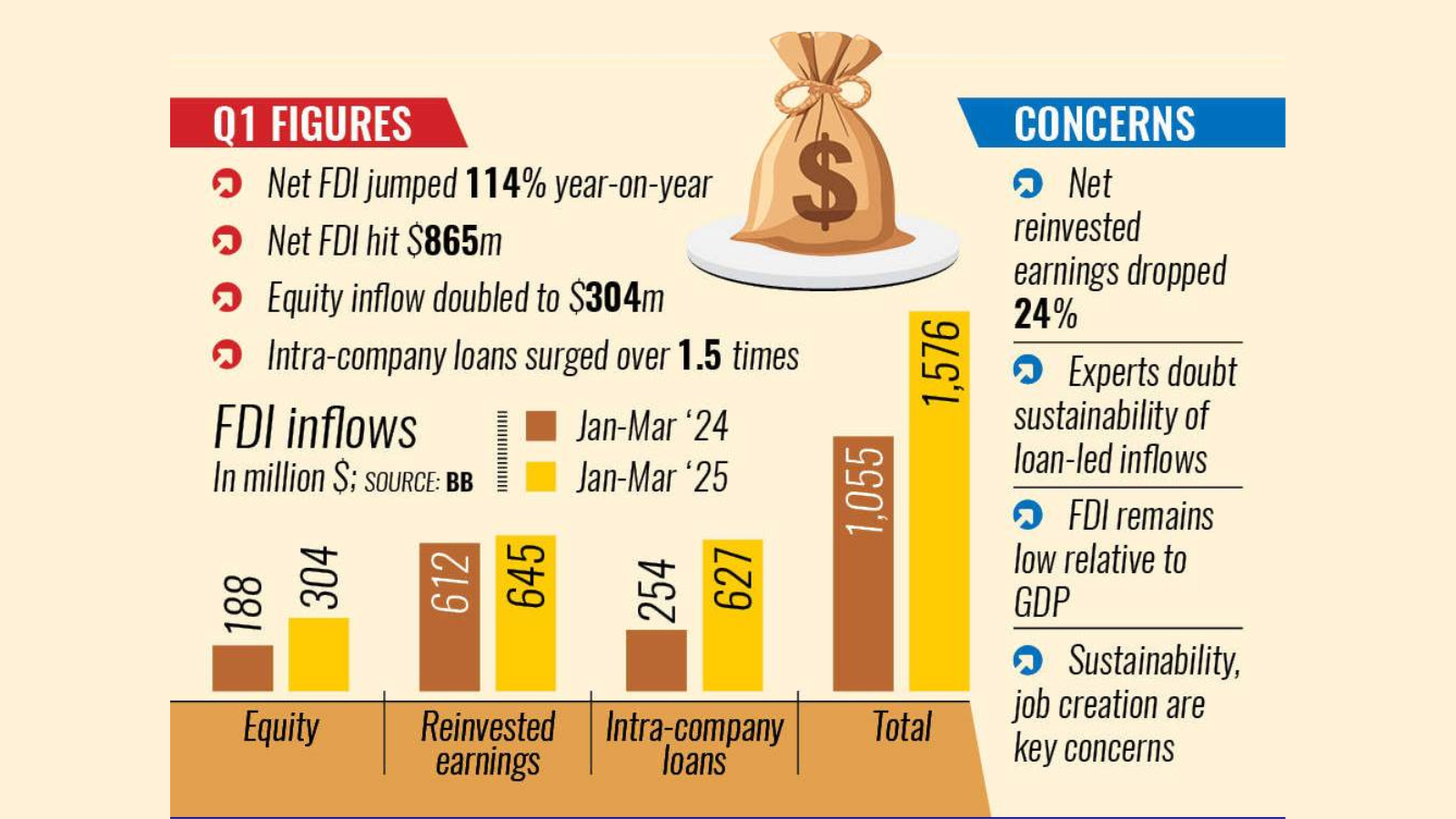

Most of this year's increase came not from new investors betting on Bangladesh's potential but from reinvested earnings and intra-company loans—money already in the country.

The most telling indicator of investor sentiment, equity capital, fell by nearly 17 percent, from $667.56 million to $554.77 million in FY2024-25, according to data from Bangladesh Bank (BB).

Equity capital fuels industrial expansion, drives technology adoption, and creates jobs. It is the portion of FDI that builds new factories rather than merely sustaining old ones. It represents fresh confidence, new entrants, and long-term commitment.

So, when equity capital drops even as total FDI rises, it suggests that existing investors are cautious, and new ones are staying away.

"Bangladesh simply isn't ready for serious FDI," said an executive member of the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, citing gas shortages and unreliable electricity as key deterrents. These problems are not new, but their consequences are becoming harder to ignore.

Reinvested earnings in FY2024-25 rose to $758.11 million, accounting for 45 percent of total FDI, according to BB data. On the surface, this might appear to show investor confidence. But are companies reinvesting because they want to, or because they have no choice?

Industry insiders say profit repatriation has become increasingly difficult amid the ongoing foreign exchange crisis. Many firms are rolling over their profits simply because they cannot remit them abroad.

"That's not expansion; that's entrapment," said one expert.

Even more volatile are intra-company loans, which tripled from $133.03 million to $373.36 million, according to BB. These short-term liquidity infusions from parent firms usually cover operational expenses, not long-term investments. They can vanish as quickly as they arrive—an unsettling prospect for a fragile economy.

BIDA, however, cited examples of declining FDI in countries like Sri Lanka, Chile, Sudan, Ukraine, Egypt, and Indonesia. But such comparisons are misplaced.

Unlike those economies, Bangladesh is still growing steadily and preparing for graduation from least developed country status. It also requires far higher FDI to sustain its growth and transition to a developing economy.

A fairer comparison would be with regional peers like Vietnam and Cambodia. In 2024, Vietnam's FDI reached $38.23 billion, up 4.4 percent from the previous year, while Cambodia attracted $8.1 billion.

Political uncertainty continues to weigh on investor confidence, with FY2024-25 beginning amid unrest and a change of government. Bureaucratic red tape remains stifling, with up to 42 approvals required to set up a factory.

The banking sector is mired in non-performing loans, while the capital market offers few viable exit routes for foreign investors.

Infrastructure gaps persist—unreliable power, inefficient ports, and costly logistics all drive up business expenses. And although Bangladesh boasts a large, young population, the skills gap continues to erode productivity and confidence.

In a press release issued recently, BIDA said, "FDI usually declines after political unrest. In this case, the opposite occurred." It's a fair point. But without meaningful reforms, this increase risks being a short-lived exception rather than the start of a sustained turnaround.

To reverse the slide in equity capital and make FDI truly count, reforms must go beyond numbers on paper.

The investment process must be streamlined through a genuine one-stop service. Policy consistency and legal transparency must become the rule, not the exception. Infrastructure—especially in power and logistics—must improve in practice, not just in plans.

And most importantly, Bangladesh must equip its young workforce with the skills demanded by modern industries through real investment in technical and vocational education.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments