The unpaid household labour GDP ignores

At dawn, 45-year-old Yasmin Ara rises before the rest of her family.

She prepares breakfast, packs lunches for her three children, and ensures they are ready for their classes. Once they leave, her work continues -- cleaning, doing laundry, planning the next meal, and caring for her elderly in-laws.

Her day becomes an unbroken cycle of caregiving, cooking, tutoring, and managing the household, all on her own. The skills she once honed at university have faded, replaced by expertise in managing domestic duties.

Despite staying up late and getting no rest, no salary, no promotion, no economic security, only exhaustion -- society views her as an "unemployed housewife" who "does nothing."

"Having a degree in Economics, I had dreams of working in a bank, of being financially independent," Yasmin recalled. "But every time I thought of stepping out, there was always something at home that needed me more."

Yasmin represents the millions of women excluded from the labour force, who say that family and household work is a significant setback to their employment. With no affordable childcare options and deeply ingrained societal expectations, she made the difficult choice to become a full-time homemaker.

Yet, while her husband's 9 to 5 job is rewarded with a salary, hers remains invisible. If Yasmin were compensated for every task she performs daily, her earnings would exceed those of many professionals.

For example, a full-time house cook typically earns between Tk 5,000 and Tk 10,000 per month, while a domestic worker for cleaning and laundry is paid Tk 3,000 to Tk 5,000.

A tutor for a school-going child would cost Tk 5,000 to Tk 15,000, and an elderly caregiver might earn between Tk 12,000 and Tk 25,000. Additionally, a personal assistant for errands usually commands a salary of around Tk 7,000-15,000.

Outsourcing Yasmin's work would cost between Tk 32,000 and Tk 70,000 per month -- far surpassing the median salary of many middle-class professionals.

"If I were paid for everything I do, I'd probably earn more than my husband," she laughed.

THE HIDDEN WORKFORCE

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated in 2018 that globally 16.4 billion hours are devoted to unpaid care work daily.

This is equivalent to 2 billion people working full-time without pay, or about 25 percent of the world's population.

If valued at an hourly minimum wage, this unpaid labour would constitute 9 percent of the global GDP, amounting to $11 trillion.

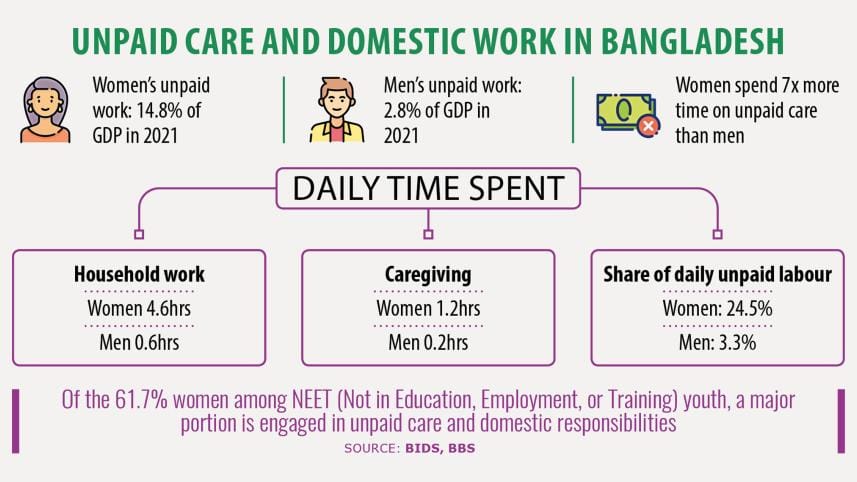

A 2024 study by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) revealed that the economic value of women's unpaid household and caregiving work is estimated at Tk 5.3 trillion, equivalent to 14.8 percent of GDP in 2021. In contrast, men's unpaid contribution amounts to only 2.8 percent.

It found that women in Bangladesh spend seven times more time on unpaid household and caregiving work than men.

Women spend 4.6 hours daily on household tasks, while men spend only 0.6 hours. Similarly, women dedicate 1.2 hours per day to caregiving, while men spend just 0.2 hours.

While men dedicate only 3.3 percent of their time to these duties, women devote a staggering 24.5 percent of their daily hours to unpaid labour.

The study also shows that on average, women spend 1.2 hours on paid and self-employment, while men spend 6.1 hours.

This estimate used the daily wages of unskilled workers, like construction or day labourers. For rural women, it's Tk 37.5 per hour, and for urban women, it's Tk 43.5 per hour.

However, this doesn't fully account for the value of household and caregiving work, which requires skills and emotional labour.

When adjusting for the skills and emotional factors involved in care work, such as knowledge of nutrition, medicine, and emotional intelligence, by increasing the reference wage for unskilled workers, the value of women's unpaid care work in Bangladesh is estimated to be 18.5 percent to 19.6 percent of the GDP.

In 2015, the Manusher Jonno Foundation commissioned the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) to research women's economic contributions and found that the value of women's unpaid household work was 76.8 percent of GDP in fiscal 2013-14 if additional women were hired to replace them.

If the woman in a family did the same work for pay in another family, the value would be equivalent to 87.2 percent of GDP.

As per the Labour Force Survey 2023, among the youth who are Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET), 61.7 percent are women, with family and household work serving as a significant setback to their employment opportunities, alongside institutional barriers that limit their labour market participation.

DOUBLE SHIFT

Even for women with paid jobs, the burden of unpaid work never lifts. Without reliable childcare or flexible work policies, many working mothers are overwhelmed, torn between professional duties and family responsibilities.

Tilottoma, a 32-year-old private employee who returned to work when her baby was just five months old, feels the weight of juggling two full-time jobs. With no one in her nuclear family to help care for the baby, she struggles through each day in survival mode. Her husband, a banker, barely has time to share the load.

Unable to find affordable childcare, Tilottoma brings her baby to work, where her productivity suffers. Her workplace offers some flexibility, allowing her to work from home at times, but that only shifts the chaos.

"People think working from home means more time for family. In reality, it means cooking with a baby in my arms while taking office calls, or working on my laptop, sitting the baby in front of a TV, which is very age-inappropriate, yet I have no other options," she said.

"There are often days when I break down. I scream. I cry -- holding my child in my arms, knowing she needs me, especially when she is physically unwell, but I just can't give her my attention when I have deadlines to meet," she added.

"And yet, quitting is not an option. My job is a financial necessity. It's soul-crushing. It feels like I have no life left at all," she said.

Maisha Mubassara, a 29-year-old government teacher and mother of two, faces similar struggles. Despite spending nearly half her income on daycare and domestic help, there's no rest after work. The challenges don't stop when she gets home.

"When I come back, there's no time to breathe. I have to take care of the children, feed them, and put them to sleep. My work never really ends."

COUNTING WHAT COUNTS

Shaheen Anam, executive director of MJF, stressed that recognising unpaid care work is essential for social change.

"Women are primarily responsible for the health, hygiene, food security, and overall well-being of the family. By making their contributions visible and formally acknowledged, it will elevate their status within households and society. This recognition could also reduce discrimination, domestic violence, and early marriage," she said.

Fahmida Khatun, executive director of CPD, echoed the same.

"When we dismiss this labour by saying 'they don't do anything,' it undermines their contributions. This attitude can escalate to mental and psychological abuse. Formal recognition would improve women's social, familial, and economic standing," she added.

Farah Kabir, country director of ActionAid Bangladesh, asserted that recognising unpaid care work is not just a developing world issue -- it is a global concern.

"Acknowledging this work is crucial to respecting and valuing women's strength and contributions. Without recognition, women's labour remains invisible."

She further said, "At the family level, recognising unpaid care work encourages redistribution of responsibilities, increasing efficiency. At the societal level, it fosters respect for women and influences behavioural change."

Kabir stressed that recognition must come through policy reforms, budgetary measures, and behavioural change, which will take time.

"Childcare support, for instance, is being discussed, but more work is needed at the policy and budget levels," she said.

A 2024 UNDP report highlighted that integrating the care economy into social protection is key to equity, resilience, and inclusivity.

"By investing in policies that support women's participation in the economy, such as affordable childcare, paid parental leave, and flexible working arrangements, societies can harness the full productive capacity of women," it mentioned.

THE GDP GAP

Currently, the existing GDP framework, guided by the System of National Accounts (SNA), does not account for unpaid care work.

However, experts have long advocated for the inclusion of unpaid care work in an extended System of National Accounts (SNA) through a satellite accounts system rather than integrating it into the main GDP framework.

In line with that, in 2023, the then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina instructed the Planning Commission to explore ways of including unpaid care work in Bangladesh's GDP calculations.

Asma Akter, deputy director of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), said, "Since unpaid care work is not exchanged for money in the formal market, it falls outside the scope of GDP measurement. That is why an alternative method is needed."

She added that efforts are underway to develop a new calculation model.

The newly formed Women's Affairs Commission Chief Shireen Huq confirmed that their reform proposals include recognising unpaid care and domestic work and assessing its monetary value in economic calculations.

Naila Kabeer, feminist economist and emeritus professor of Gender and Development, however, argued that GDP measurement is flawed as it ignores the billions of hours of unpaid care work mostly done by women.

GDP only counts goods and services that are bought and sold, failing to recognise essential activities like childcare, housework, and elder care.

As a result, nearly 90 billion hours of unpaid care work worldwide go unaccounted for, even though society would collapse without it, she mentioned in her paper "Radical Pathways Beyond GDP: Why and how we need to pursue feminist and decolonial alternatives urgently", published by Oxfam.

Kabeer highlighted alternative ways to measure progress, focusing on well-being, social justice, and sustainability rather than just economic output.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments