Carbon debt-free future for every child

Bangladesh could become a global waste hotspot due to rapid urbanisation and economic growth. However, the government has taken the ambitious target of reducing the waste impact to half by 2025 and achieving a global standard level by 2030

I became fully aware of the environmental challenges that we face when I visited Boracay Island in the Philippines a few years ago. The amazing picturesque beaches with white sand and blue lagoons were disturbed by the over-interest of tourists like me.

The case of Boracay Island represents the situation of our whole planet in general: Humans have unequivocally warmed the planet by more than 1.1°C since pre-industrial times and we are on track to exceed 1.5°C within two decades, if not before.

That is why global climate scientists have sounded the 'Code Red Alarm' for humanity which is true for every country, including Bangladesh. Despite contributing only 0.6 per cent to the global emission, Bangladesh ranks seventh on the list of countries most vulnerable to climate devastation, according to the Germanwatch's 2021 Global Climate Risk Index.

A 2018 US government report found that a whopping 90 million Bangladeshis, or 56 per cent of the population, live in "high climate exposure areas," with 53 million being subject to "very high" exposure. We have lost around $4 billion in economic value since the 2000s as an outcome of climate change. We all are under threat and we need to act like that for a livable planet to be won this decade.

We all have roles to play because we are responsible at the national, organisational, and personal levels. Together, we are using more natural resources every day than the earth can reproduce, technically borrowing resources from our next generation. However, we should not use what is our children's and make them suffer.

Working to improve the health of the planet is something that is not charity - rather a long-term business strategy. That is why progressive business organisations like Unilever have taken a global stance on the environment because we feel that our business will only exist if our consumers are there, and we need to help our consumers by helping them protect our planet.

That is why we have put sustainability at the core of our business and we see this beyond philanthropy. We want to work on innovation and adaptive social change by taking collective actions. We all know how collective action is rewarding if our intention is good and our strategy is right.

I would like to mention the Social and Community Foresting Activity in Bangladesh as a prime example of effective strategy and participatory development.

Back in the 1980s, we were losing around 2 per cent to 3 per cent of forest cover every year. Our government, in association with international development organisations like the Asian Development Bank, designed an intervention involving the poor, landless rural farming families to plant and take care of trees, on the roadside, and free land.

The Social Foresting project was a major success of the government which not only helped increase the forest area of the country, create tree cover along highways and basic protection in the coastal area but has also created a value chain and mindset shift among people.

It is seen worldwide that plastic consumption in any country increases simultaneously with income level, urbanisation, and economic growth. Bangladesh's annual per capita plastic consumption in urban areas tripled to 9 kg in 2020 from 3 kg in 2005 with Dhaka's annual per capita consumption of plastic being 22.5 kg.

Plastic is a valuable material but there is a lot of plastic pollution in the environment and only a third of the waste plastic is collected and recycled. According to a World Bank Group research, 24,000–36,000 tonnes of plastic waste are disposed of every year around canals and rivers around Dhaka only.

Plastic waste is one of the major reasons behind water-clogging after rains in urban centres like Dhaka and Narayanganj. Next time when you are stuck in traffic on a rainy day, remember that you are responsible for this as well!

However, we must start working to find a suitable, practical solution for us as well. For example, as a consumer goods company, one of Unilever's (guiding philosophy) compass priorities is to improve the health of the planet and we intend to achieve that by putting our efforts into a waste-free future. We have taken a bold first step to challenge the problem as we wanted to contribute to finding a sustainable solution for single-use plastic and flexible packaging in cities like Dhaka and Narayanganj.

I remember my market visits to Narayanganj, a vibrant and buzzing business hub with the lowest percentage of poverty of the country. But you would still see polythene bags thrown on the roads, water-clogging and polluted Shitalakkha river.

According to a baseline study by PwC, 65 per cent of the 900 tonnes of waste generated per month is not managed properly and the overwhelming majority of unmanaged plastic includes LDPE (polybags) and other plastic groups, including multilayer packaging (MLP). These plastic wastes end up in the environment as they have less or no recycling value compared to other forms of plastic.

However, in the National Action Plan for Sustainable Plastic Management, the government has set a target of recycling 50 per cent of plastics by 2025. But this will not be possible if we do not solve the SUP issue. From Unilever, we decided that we also want to contribute to that cause by transforming the way we use resources and making an efficient ecosystem for a circular economy.

However, as a business organisation, we only have consumer insights and reach but have no experience in running social intervention projects. Thus, along with Narayanganj City Corporation (NCC), we have also partnered with the UNDP and the ESDO to start a three-year project to transform the plastic waste management of Narayanganj into a circular model through capacity building, community empowerment, and behaviour change.

As the largest municipal-backed waste management project, we have lots of learning in the initial phase of the project. The project does not aim to provide dump trucks and waste bins. Rather, we want to work with partners to change waste management practices of both consumers and collectors, by ensuring that the plastic waste has better recycling value.

Our first-year objective was to geographically reach all wards of the NCC by strengthening the existing waste collection channels and experimenting with different intervention models. Our other objective was to make the process sustainable as we are also trying to increase the income of the waste collectors and have empowered over 1,300 collectors on how to segregate waste for better value, increasing their income.

The learning is very encouraging and we are planning for systematic engagement of the government, industry peers, media and most importantly, the citizens of NCC to scale up the project. We have already started to replicate the model in Dhaka and Chattogram city corporations. We know that we will have to rewire, reengineer, and redesign many aspects of our work, but we believe the process needs to start and improvement areas will always be there.

Along with large municipal-backed projects, we have also experimented with other intervention models and partners, including start-ups to find effective, efficient, and scalable interventions to solve the plastic waste problem in Bangladesh because as per International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh could become a global waste hotspot due to rapid urbanisation and economic growth. However, the government has also taken the ambitious target of reducing the waste impact to half by 2025 and achieving a global standard level by 2030.

We believe learning from projects like the NCC Waste Management project would really contribute to formulating national-level strategy and engage people to change their attitudes and behaviour.

We do have the power to save the world together. And we have to do it because, for us and for our next generation, there is only one earth.

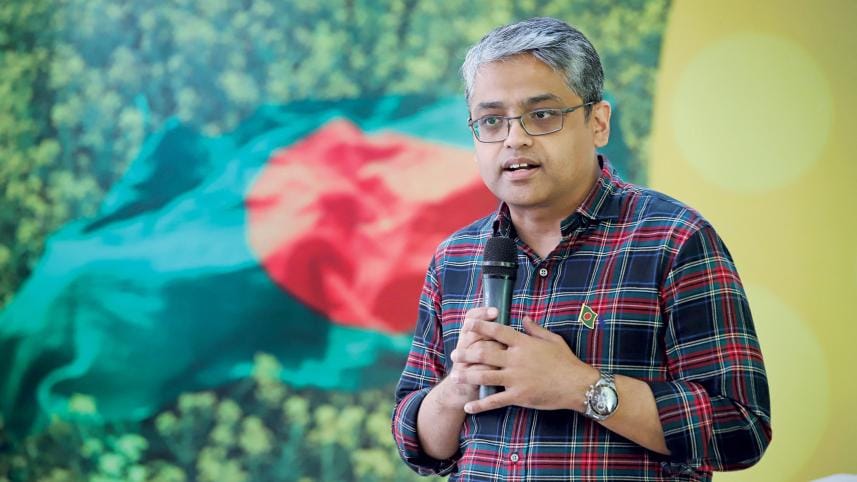

The author is chief executive officer and managing director of Unilever Bangladesh Ltd.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments