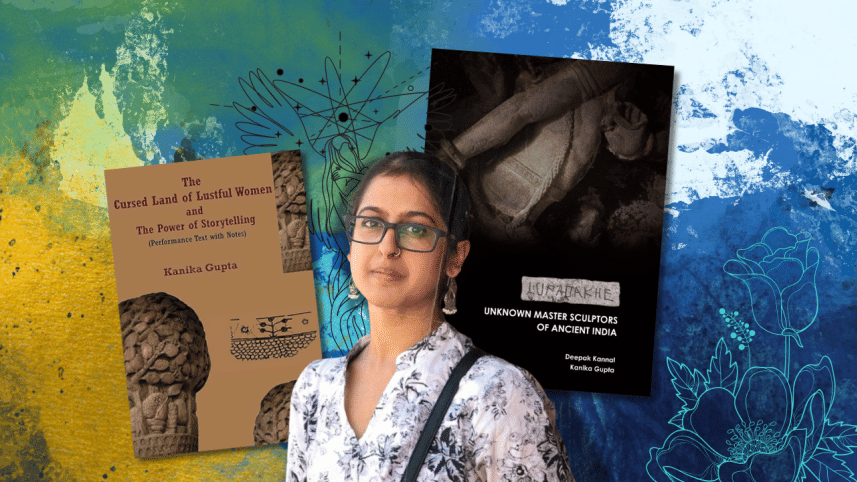

Reclaiming the unwritten: Kanika Gupta on colonialism, embodiment, and the art of remembering

Kanika Gupta is an art historian, trained dancer, filmmaker, and author whose work bridges the worlds of ancient Indian art, mythology, and storytelling. She holds a Master's in Art History from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda, Gujarat, and a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, specializing in the study of ancient Indian motifs.

An accomplished writer, Kanika has authored Lupadakhe—Unknown Master Sculptors of Ancient India (2019) along with numerous research papers on Indian sculpture, aesthetics, painting, and mythology. Her latest work, The Cursed Land of Lustful Women and The Power of Storytelling (2023), continues her exploration of history, art, and cultural narratives.

Kanika was also the only Indian selected for the Slovene Ethnographic Museum's artist-in-residence for the TAKING CARE Project, an initiative focused on reinterpreting ethnographic collections through contemporary perspectives. Through her diverse body of work, Kanika brings forgotten stories, ancient artistry, and untold histories to life, making them accessible to modern audiences.

Gupta shares her insights on reclaiming forgotten histories, reimagining myths, and connecting ancient narratives to contemporary ecological and social concerns.

Namrata: Your early work, Lupadakhe: Unknown Master Sculptors of Ancient India, examined anonymity and authorship in ancient sculpture, while your recent book, The Cursed Land of Lustful Women and The Power of Storytelling, stems from performance and mythology. How do you connect these two seemingly different practices?

Kanika Gupta: That is a very insightful question. My aim was to move beyond purely textual analysis and offer an embodied, affective way for audiences to engage with the past, particularly the stories of women and forest communities, whose histories are rarely recorded in canonical texts and often preserved through oral and performative traditions. Artistic practice, for me, is incomplete without explaining its roots, its sources, and the ethical considerations behind it.

We live in times when ecological destruction and hyper-capitalism threaten both nature and indigenous communities. From Ladakh to the Nicobar Islands, from the Western Ghats to urban forest patches, survival is owed to those who have resisted erasure, often at great cost. Any engagement with ecology in art must recognise this struggle; otherwise, it risks being shallow or hypocritical.

Performance allows bodies, memory, and myth to become agents of protest and resilience. Stories, oral histories, and ancient wisdom live through enactment, carrying lived experience in a way text alone cannot. The artist's note is pivotal—it documents my scholarly and creative process, explains ethical decisions in retelling ancient tales, and provides a pedagogical framework for understanding the performance.

Ultimately, the work creates a space where forgotten histories are remembered and re-experienced, allowing the wisdom of the past to speak to the ecological and human crises of our present.

Your recent book presents not just stories but a devised performance text with notes—an unusual format. Why was it important to pair the performance with reflective commentary, and how does performance itself become an archive of forgotten voices?

I have always wanted to move beyond purely textual analysis and offer an embodied, effective way for audiences to engage with the past. This approach is particularly important when dealing with the stories of women and forest communities, whose histories were rarely recorded in canonical texts and were often preserved through oral and performative traditions. For me, artistic practice is incomplete without a strong theoretical framework grounded in lived experience. It is essential to explain where a work comes from, its roots, and the ethical considerations that shape it.

I do not deny that theory is also a luxury of a sort and in times like ours many cannot afford it. And yet, these are the tools that I find in my hands, and these I shall use. Bodies also become agents of protest and resilience in the face of a new wave of colonialism.

Our times are defined by ecological destruction, propaganda, and hyper-capitalism, where indigenous communities and nature are the most affected. From Ladakh to the Nicobar Islands, from the Western Ghats to urban forest patches, much of what survives has endured because communities resisted erasure, often at enormous cost. To speak of ecology and narrative without acknowledging these struggles would be shallow. It is only through awareness and the search for alternatives to the normative created by hyper-capitalism that we can hope to reconnect with the essence of being human.

Performance allows bodies, memory, and myth to become active agents of protest and resilience. Myths, oral histories, and stories come alive in enactment, carrying the weight of shared experiences across time. In this way, performance itself acts as an archive, preserving and transmitting voices that might otherwise be silenced.

The artist's note in the book is central to this endeavor. It documents my scholarly and creative process, lays bare the sources I drew upon, and explains the ethical and intellectual scaffolding behind the performance. It provides a pedagogical framework, allowing audiences to understand the complexities of translating ancient narratives for a contemporary context.

Ultimately, this work creates a space where forgotten histories are actively remembered and re-experienced. By reanimating these voices, performance allows the wisdom of the past, ecological, cultural, and human to speak directly to the urgent challenges we face today, making history a living, participatory, and ethical dialogue.

The Cursed Land of Lustful Women draws from ancient motifs with the female entwined with the tree, the yakshi, and the sacred river, to address today's ecological crisis. How did your research on ancient goddesses and yakshinis shape your own understanding of climate change? What do you believe these myths can teach us about living more responsibly with nature?

The cult of yakshi reflects a long history of nature worship, showing that communities have existed in harmony with their environment. Even in urban spaces, families and individuals carry inherited memories and cultural practices, whether traditional or modern, that shape who we are and what we aspire to become. History, therefore, has much to teach us about human relationships with nature and how these have varied across times and places.

Ancient literature is full of stories illustrating community conflicts over water, the felling of trees, and their consequences. One well-known example is from the Mahabharata, where the Pandavas burn the forests of Khandavaprastha to clear the land. Entire communities are destroyed, except for Maya, a master architect who survives and pledges to build the Pandavas a palace if spared. This story forms an important part of my performance, highlighting the intertwined fates of forests and the people who inhabit them.

Today, the Gangetic valley has been effectively deforested, and few traces remain of its once-green past. The consequences are visible: rising temperatures, floods, droughts, degraded soil, falling water tables, GM foods, and growing healthcare costs. Yet society continues to ignore the communities who have survived despite the so-called progress narrative.

We rarely ask how much forest cover remains or why increasing it isn't prioritised over building roads and flyovers. Ancient stories, ecological wisdom, and lived histories collectively urge us to reconsider our relationship with nature to recognise what has been lost and what we still have the power to protect.

The title The Cursed Land of Lustful Women evokes the historical association of female desire with danger. In your retelling, you present these figures as custodians of ecological wisdom. How do you balance fidelity to tradition with feminist reinterpretation, and do you see your work as part of a larger feminist historiography of Indian art and literature?

We must not forget that traditions, like hierarchies, exist in plural. We live amidst layered hierarchies: colonial, Brahmanical, patriarchal, and patriarchy exists even within communities that claim equality. The same multiplicity applies to the past. There was never a single universal tradition, nor could there be. What kind of tradition, and which past, are we even referring to?

Feminism, as we understand it today, is primarily a modern concept. I use these contemporary ideas to reinterpret ancient storytelling frameworks, but there is enough in Indian history to suggest the existence of social structures and ideas that differed from strict patriarchal norms. Feminism emerged in a largely patriarchal world, but it is entirely plausible that certain times and communities functioned without entrenched patriarchy, in such contexts, feminism as a concept may not have been necessary or might have been expressed differently.

Today, when patriarchy remains deeply entrenched, particularly in India, it becomes natural for an artist to reflect on these issues in her work. Yet, a broad, unified feminist movement in India has never fully existed and may not for some time, owing to divisions along caste, class, and entrenched gender norms. My reinterpretation, then, is both an artistic and ethical act—to excavate possibilities in history that challenge patriarchal assumptions and to imagine alternative modes of social and ecological relationships that were always part of our plural past.

Much of your scholarship engages with the margins including unknown sculptors, silenced women, and forest communities. How do you approach this act of recovering or revoicing the forgotten? Do you see this as a political act as much as an aesthetic nor historical one?

I think there can be nothing that can be apolitical. We are political before we are born. What is personal is coming from what is political. However much we may try if you really look into it, it is not possible to segregate the political from anything.

Is aesthetics not political? A study of the history of aesthetics will tell us that political enquiry and backdrop is at the centre of it. And I have repeatedly said, aesthetics is one of the most powerful tools of coloniality. It is through cultural and aesthetic hegemony that one group of people can completely take over or annihilate another community. Colonialism has not ended, the once colonised are still colonial in their minds, in their aesthetics. Economies function the way they do because of a history of politics and

Colonialism, where culture, art, aesthetics are put on a pedestal is decided by economics, who holds the bag of money.And then there are hierarchies within the cultures that were colonised and continue to be colonial. The concept of nation state has led to more hegemony and unification of culture has led to erasure of many other cultures that were rich. And what is more dangerous is that when these colonised nation states become colonisers themselves within a capitalist structure the erasure is faster and more decided, it is fatal. And the erasure is not simply that of communities and their identities, it is also of the environment and the nature in which these nation states exist.

Your work seems to suggest that storytelling itself whether through books, performance, or film, can be a method of research, not just a form of communication. Could you elaborate on how you use storytelling as methodology? What does it allow you to access that conventional scholarship might not?

Techniques of storytelling and their diversity itself is a starting point. Before the written word there were stories. And when we come to textual sources, those which have been written down and preserved over generations and are available to us today, it is imperative to ask why certain texts are preserved and some are lost. And besides the written word there was this huge oral tradition which depended upon storytelling. Much of that is lost to us or has transformed and reaches us today through the mouth of the opponents.

It is significant to understand which stories we choose to tell. Where are they coming from? Many of these stories may have roots in some of the larger mainstream religions, but there are many that come from a different and diverse set of traditions. It is very important to recognise this. And then there is how to tell that story. I was trained in a traditional Indian dance form called Kathak, and a lot of it came from Brahmanical outlook. I wanted to break that and search for stories that are more rooted in the soil, in communities that live with nature and stories in which women have identity and question power structures. But in order to do this I realised that I would have to break free from stylistic dictates, break away from the rigidity of costume, stage, and the structure of Kathak itself.

Interestingly, I discovered that the history of Kathak is embedded in a very non rigid structure, and it welcomed different interpretative frameworks within style and content. I wanted to see if this diversity can still exist and the openness offer a fresh perspective.

Beyond writing and performance, you curate exhibitions, work with museum collections, and lead heritage walks in Delhi. How does public engagement fit into your work, as an extension of research, or a different form of storytelling?

Working within the arts and art history for me means essentially working with people and communities. My aesthetic enquiry comes from a study of its historicisation, from a search for diversity within aesthetics and the sidelined aesthetics. This can naturally not be complete without its audiences, and its roots already lie in communities. My walks and museum work are based on my enquiries on aesthetics and the narratives thus ignored.

Having traversed art history, dance, performance, and ecology, what directions do you see your work taking next? Are there themes, myths, or art forms you feel especially compelled to explore in the future?

I am keenly working on developing an archive of indigenous and endangered languages within the region of northern Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh. In this my colleague and friend Akash Kumar Sahu, currently Head of Department and Professor of History at Fakir Mohan College in Balasore, is collaborating with me. We have been recording oral histories of Sambalpuri handloom weaving communities and indigenous communities and are hoping to find support from an institution that can host the archives. One of the most thrilling interviews that we have done is that of the poet Haldhar Nag. He is truly an archive of a knowledge system that is deeply rooted in the region he belongs to. It has been a great learning experience. We hope to continue our oral history project and extend it to documenting folklore within these languages among other things.

Having taught for nearly a decade at NID and at IIT Bhubaneswar, how has this experience influenced your approach to art, storytelling, and research? What insights from students inform how you connect ancient narratives to contemporary concerns?

Teaching has been a great learning experience. Sometimes I feel I learn more than the students (smiling). It is always so refreshing to look at an idea or concept with fresh eyes or a completely open mind. At IIT Bhubaneswar I had the opportunity of meeting so many students from Odisha and Chhattisgarh and it has been so enriching. It was through them that I got to know of so many languages that are now endangered, and it prompted me to work further on my oral history project. I understood how languages are viewed by their generation and how different mediums of art open a completely different dialogue in different spaces.

Being at any NID is always a creatively refreshing experience. And I am able to view my own theoretical framework through a different lens, and that adds to my understanding tremendously.

Your documentary It Was in Spring and ongoing oral history projects reflect a deep commitment to preserving lived memories and cultural textures. How do these projects complement your work with mythology and performance, and why do you think it's important to document personal histories in today's rapidly changing world?

Stories are at the base of any aesthetic framework. It is in the myths, stories, and folklore of different communities that I search for an aesthetic. I think it is impossible to create new aesthetics without a historical grounding, a reference to collective memories and stories that come from a distinct tradition.

It is possible to preserve a language, a whole cultural structure, its aesthetics, an entire knowledge system around it, only by creating art in that aesthetics, only by writing literature and poetry in that language. And it is through personal stories that I hope to build such an archive.

Namrata is a writer, a digital marketing professional, and an editor at Kitaab literary magazine.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments