Sonnet of the riverbank: Remembering Al Mahmud, the poet

Some poets arrive like rain on parched soil—needing no defense, only recognition. Al Mahmud (1936–2019) was one of them. And yet, in the usual crookedness of history, we have found ourselves having to defend what should already have been canonised. There was a time—not long ago—when his name unsettled literary editors in Dhaka, when praising Sonali Kabin (1973), risked being branded reactionary, and even admirers hesitated to carry his new poems to print. I remember it vividly: the early 1990s, when Muhammad Nizamuddin and I set out to compile the special Upama issue on Al Mahmud. We went door to door across Dhaka, knocking on the confidence of poets and critics, asking for essays. Most refused. One professor, with oracular weight, told us: "Time is not in favor of Al Mahmud." As though poetry was supposed to submit its worth for time's approval.

And yet Sonali Kabin (1973), like Farrukh Ahmad's Shaat Shagorer Majhi (1944), is what the great George Kubler, the giant of art history, once called a "prime object". In The Shape of Time (1962), the Yale art historian introduced the enigmatic yet generative idea of "prime objects"—singular works that initiate new series of forms, patterns, or techniques. These are not simply "firsts" in a chronological sense; rather, they are works so decisive in conception that they generate whole families of replicas, copies, derivations, variants, and discards. "Things create things," Kubler writes, emphasising not inheritance but propulsion. A prime object is not an origin so much as a rupture—something that breaks through and, by doing so, alters the sequence of what follows.

Kubler's "prime objects", in other words, are works that change the "shape of time" by compelling all other works to respond to them. Bengali Muslims don't have many: Agnibina (1922), Shaat Shagorer Majhi (1944), and Sonali Kabin (1973)—these are the keystones. The rest are echoes, derivations, or polite variations. What made Sonali Kabin different was not just the erotic cadence or the earthy Bengali sensuality—it was the sudden appearance of a poetic voice that neither fled from the village nor mimicked the city, that poured regional vocabulary into metrical forms without ever sounding folkloric, that conjured the Meghna and Mahua and cow-dung-dappled courtyards with the ease of one who had no need to exoticise.

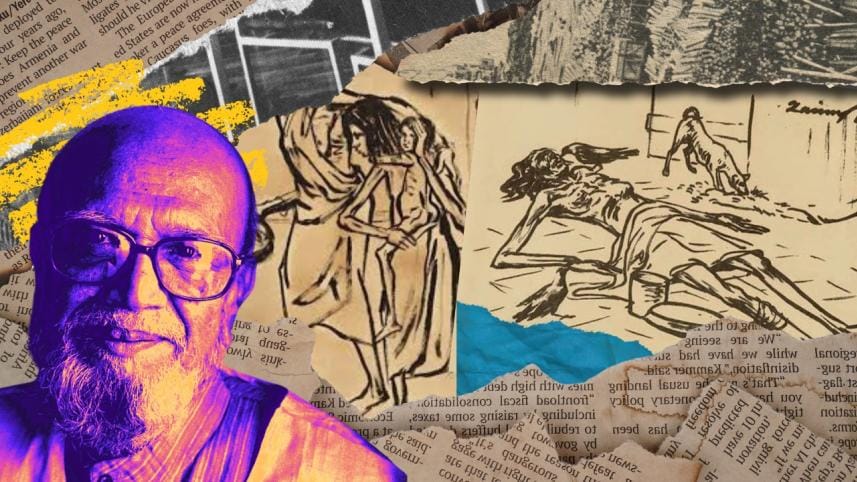

Critics liked to compare him to Jasimuddin. It was a mistake. Jasimuddin wrote the village from within the lyric logic of its innocence; Al Mahmud wrote it from within the contradictions of historical survival. His love poems are not about lovers in cafés or students in half-rented hostels—they are about women with 'shabari' feet and tribal rhythms, about nakedness in rice fields, about eros as ecology, about bodies cast in the same grammar as land. If Sunil Gangopadhyay wrote love in a Kolkata register, and Shakti Chattopadhyay in tantric ambiguity, Al Mahmud wrote it like a peasant Zainul Abedin might have drawn—with hard lines and muscular shadows, their contours shaped by classical training in European art history at the Calcutta Art School, where names like Michelangelo loomed large and Principal E.B. Havell could not have imagined how such formal rigour would one day be retooled for famine sketches.

Later, Zainul would channel those same classical skills—honed in part through his exposure to Michelangelo and other Renaissance masters—into depicting Bengal's peasants as monumental figures, echoing the muscular dignity of Sistine bodies. But it was first in the famine sketches—drawing dying bodies with lines borrowed from Europe—that he translated classical form into a language of Bengali suffering. There is a continuity here worth tracing. Farrukh Ahmad, a communist in the 1940s, wrote his famous poem Lash (1944) after witnessing the dying on Kolkata's famine-stricken streets—bodies the Indian half of Bengal, still enthralled by a certain Shankarian metaphysics where death and hunger are 'maya' and only Brahma is real, refused to see. After all, why sketch famine if the world itself is an illusion? At that very moment, Zainul was sketching those same bodies, while their dominant non-Muslim counterparts were still searching for heroes in the 'puranas' and Rajput legends. Unlike their peers, whose artistic traditions often turned toward metaphysics or allegory, these Muslim poets and painters grappled with famine, dislocation, and injustice as immediate, embodied realities. Al Mahmud's muscular rural eroticism continues that thread—not in imitation, but in inheritance. A modernity not of the city, but of the broken field, the ploughed body, the unwitnessed hunger. And behind it all was a poet who did not believe love was private. His was not the romance of soft modernity, but the heat of ancient Bengal's hunger, sweat, loss, and memory.

He loved the sonnet, but only in the sense that he could house ancient textures within its frame. The craft never announced itself. No elaborate technique, no formal pyrotechnics. His poems never tried to impress. They moved with the conviction of someone who had no patience for experiment-for-the-sake-of-experiment. Technique, he said more than once, is the substitute of those without poetic metal in them. He had metal. He had rhythm. And he had an instinct for metaphor that would make even his enemies pause. Even in the poems where Islam, Muslim history, or classical narratives appear, there is no trace of sermon or sanctimony.

Al Mahmud, in moments of frustration, would often quip: "woju kore sahitya hoy na"—you can't do literature after performing ablution. What he meant was not merely that ritual purity and creative labour are mismatched, but that literature and religion are fundamentally different modes of being. When certain Islam-lovers began demanding he write only about Muslim history or themes, he reminded them—bluntly and repeatedly—that literature is not a branch of preaching. It comes from a different impulse, and it obeys no doctrine.

It's a line I remember well, because it came during a long interview I conducted with him for that Upama issue in 1994—a special issue that would become a small act of resistance. The interview was one of the most electric I have ever done, and his answers remain legendary. I had been working through Derrida, Paul de Man, and post-structural theory at the time, and at one point I pressed him on Tagore's definition of the short story—that it had "no theory." I asked, hadn't theory now become part of life itself? Al Mahmud laughed, then said: "Rabindranath was right. Theory has never been part of life. And whenever you let philosophy enter literature, it will inevitably make your 'prajanan shakti' impotent."

Those are his words: prajanan shakti. Generative power. And that's what his poetry had in abundance. It had sex, soil, hunger, injustice, betrayal, belief, and myth, all thrown together in one unforgettable voice. It had sonic force and syntactic strangeness. It had metaphors you could never predict but instantly recognise. And perhaps that is why so many could not forgive him. He wasn't the poet they expected. He had come out of schoolrooms they never entered, spoken to villagers they never heard, kissed women they never met. He did not inherit the city, nor did he need it. And when the city turned its back, he kept writing. Through imprisonment, marginalisation, political exile, and career sabotage, he kept writing. Like Farrukh before him—who wrote Shaat Shagorer Majhi in 1944 without knowing whether Bengal would remain Bengal—Al Mahmud wrote with the sense that Bengali Muslim literature still had to be invented.

It begins, for many of us, with the sonnets.

The 14 sonnets of Sonali Kabin (1973)—composed over the late 1960s—have become so central to the canon of modern Bangladeshi poetry that we forget how improbable they once were. They arrived in a decade of rupture, revolution, and rhetorical excess. And yet here was something measured and sensuous, earthy and metaphysical, teeming with folk memory and ancient hunger. Al Mahmud did not write these poems as a manifesto, and yet they have the force of one. They stand not just as a personal triumph but as a reminder that poetic form is not an afterthought to meaning—it is its most intimate double.

In Sonali Kabin, Bengal is imagined not as a map but as a body—female, fertile, wounded, defiant. It is not a sanitised, civilisational Bengal but one filled with kirat, shabar, kol, bheel—the indigenous and the ostracised, the forest-dwellers and the river-people. The shabari of myth—real tribal women mythologised in the Ramayana—are here reimagined not as devotional figures but as elemental presences, closer to the soil than to scripture. This is the Bengal bypassed by Sanskrit epics and Brahminical genealogies. Al Mahmud's Bengal is not a land of temples or pilgrimage routes—it is a land of labour, hunger, and sensual knowledge. His Bengal resists not with ideology but with flesh, river, and memory.

Much has been written about Sonali Kabin, and rightly so. But too much of that writing has tried to either domesticate or dismiss him—by classifying him as a rural poet, a 'non-experimental modern', or worse, a peddler of nostalgia. These are errors. No one who reads the sonnets with care can miss their deliberate structure, their philosophical musculature, or their near-surreal tonal range. Al Mahmud, in these poems, was not retreating from modernity. He was re-rooting it in a language and geography that the self-anointed urban avant-garde had trained itself to ignore.

The terms are familiar enough: modernism, romanticism, lyricism, indigeneity. But Al Mahmud reshuffled them. He borrowed from the entire available past—Charyapada, puthi literature, archaeology, tribal lore, puran-rupkatha, and the Buddhist past of Bengal—and repurposed them into something unmistakably his own. In doing so, he gave Bengali poetry something it rarely achieves: a center of gravity.

This was not without cost. After Sonali Kabin, his work turned more inward, more historical, and more embattled. Some of the later poems stumble; others shimmer. His fiction never had the same power as his verse, but the stories—especially the unforgettable "Jalabeshya," a central story in Pankaurir Rakta (1975)—carry their own weight. "Jalabeshya" centres on a working woman from the river-trading communities, sometimes called river-companions or ferry-camp women, whose livelihood was entangled with those of the traveling beparis. In this story, the bepari—the small-time trader who ferries goods across riverbanks—is about to enter her when a deadly panakh snake springs from her jhuri (basket) and bites his forehead. She, unfazed, simply flings his body into the water. The story caused an uproar. Poets were furious, envious, bewildered. As Al Mahmud once said, bewildered critics in Kolkata—after reading his short stories in Kafela patrika—"honoured" him by calling him a haramzada. "Who is this haramzada?"—that's what they wanted to know. Even Shahid Qadri, in Bichitra, wrote that Al Mahmud's stories were better than his poems—a line Al Mahmud never forgave. It wasn't praise. It was a barb, a calculated slight, poetic envy dressed up as literary judgment.

I have read Al Mahmud countless times, quoted him endlessly, and still feel I have barely caught up. I have recited those lines about the kaker dal—the urban crows who fail to grasp the koel's music—about the rebellious bhatir kumar, about Pundrabardhana and the Buddha. Lines drawn from both Sonali Kabin and Lok Lokantar, where poems first composed during one period often reappear in later volumes, nearly indistinguishable from newer work. How many poets can sustain such consistency across time? Lok Lokantar too contains sonnets nearly identical in texture and force to the fourteen unforgettable sonnets of Sonali Kabin. Even that crow—urban, hostile, unmusical—first appeared in Lok Lokantar, alongside poems like "Dredger Balesshar," where the poet evokes a machine tearing through the riverbed just as he ploughs through the body of his 'ramani'—a sonnet that ends, memorably, by likening the dredger on the Titas to a floating iron sonnet. Even when I wince at his politics or question his later literary turns and alliances, I return. Some poets go on forever in their silence. Some poems don't wait for time to favour them. They simply endure.

So let us celebrate the one who did not wait. The poet who poured Sonali Kabin into the cracked vessel of a nation that still struggles to name its complex inheritance. To praise Al Mahmud is not to resist modernity—it is to confront it. For his poems were not backward glances nor progressive slogans, but direct, undistracted confrontations with the present—mud-slick, history-heavy, and uncannily alive.

Dr Salahuddin Ayub is Professor and Chair, Department of Criminal Justice, Philosophy, and Political Science, Chicago State University. He is the author of several books including Farashi Tattwa, Paul de Man o Shahityer Agastyayatra (Bangla Academy, 2018). Email: msalahud@csu.edu.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments