The view from the West

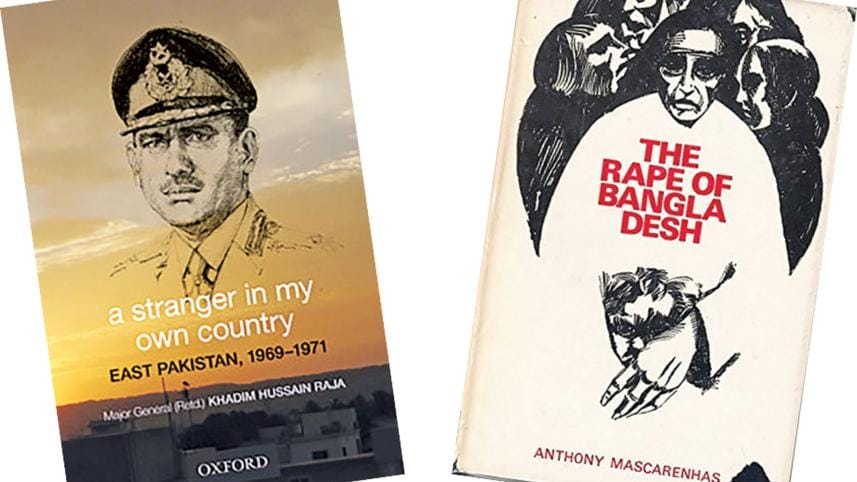

After half a century from where we began, Daily Star Books will spend all of this year—the 50th year of Bangladesh—revisiting and analyzing some of the books that played crucial roles in documenting the Liberation War of 1971 and the birth of this nation. In this sixth installment, we revisit both Khadim Hussain Raja's A Stranger in My Own Country (Oxford University Press, 2012), in which a retired general gives often problematic views from West Pakistan's perspective, and Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas' The Rape of Bangladesh (Vikas Publications, 1971), a pivotal book that changed world opinion on the then-underreported genocide of East Pakistan.

A Stranger in My Own Country by Khadim Hussain Raja

All that time spent reading up on Bangladesh's Liberation War, one can't help but wonder what went on in the minds of the other half. What their military leader had led them to commit was no less than genocide. Which is why one wonders what possible forces could've motivated one half of a nation to turn on the other half through such barbaric measures.

What were they thinking?

What did they possibly hope to achieve?

The enemy's minds turned out to be quite simple to understand, or so it is in the words of Khadim Hussain Raja, who served as a military general in the Pakistani army before being appointed as Ambassador to Mozambique. General Raja's personal accounts of the war are presented in A Stranger In My Country (2012) as the tragic fall of what could have been a great nation born from the ashes of a post-partition India.

From the book's title, one can determine the tone with which Raja narrates his side of the story—as an officer in the barbaric Pakistani army during Bangladesh's Liberation War of 1971. His description of the nation's tumultuous state of politics is as vivid as it is disturbing, with the very first chapter bearing an ominous title: "The Brewing Storm". But the book begins on a relatively cheerful note, with an eager Hussain Raja expressing his excitement about the Army War Course at the Command and Staff College located in Quetta. Following the author's interactions with Ayub Khan, just a few more pages ahead, readers are faced with Hussain Raja's perspective on the Bihari-Bengali conflicts, which is somewhat different from the accounts given by Bangladeshi writers such as Jahanara Imam and Badruddin Umar. This is because Raja sheds light on the anti-West Pakistani sentiment exhibited by the oppressed Bengalis, talking about the "... Bengali shopkeepers who […] were not even interested in earning money from West Pakistani customers".

He goes on to describe the political landscape of Pakistan in 1969. We learn of Ayub Khan's growing unpopularity from a conversation the author had with Lieutenant General Gul Hassan. We also learn about the possible misreporting of valuable intelligence by the Director General of the Inter-Services Intelligence and the Director of the Intelligence Bureau, prior to the 1970s general elections. Using detailed descriptions of battle plans being drawn and in-person meetings with military generals and intelligence officers, Raja etches a realistic portrait of military planning in a war-torn nation.

The only thing the book gets wrong is its misguided portrayal of the political landscape of the two halves of Pakistan from 1969-1971.

Hussain Raja's perspective downplays West Pakistan's oppression on its Eastern counterpart, and in a final chapter, the author claims that, "The religion of Islam was a common bond between the people of both wings (of Pakistan). However, it could not make up for the shortcomings caused by physical separation and by the differences in language and culture. The large Hindu minority […] took advantage of these differences and did all they could to emphasize and accentuate them". He then proceeds to vilify Bangladeshi freedom fighters, painting members of the West Pakistani army as victims of assault [3] and labelling the protesters as "Awami League ruffians" who would carry out arson leading to "… casualties inflicted on the Biharis and West Pakistanis". None of this compares to the chill in his words in chapter eight, narrating the events that unfolded on March 25, 1971—hours before the West Pakistani military opened fire on what Hussain Raja describes as "… a good bit of resistance from the University Halls", we read of how calmly he enjoyed teatime with his wife and friends before heading out to catch a film at Garrison Cinema.

A Bangladeshi patriot would have a hard time digesting this book in its entirety, given the unsympathetic portrayal of the Liberation War penned by a former general of West Pakistan. But it is because of the author's credentials that this book warrants a read. One might not agree with the viewpoints presented, and one doesn't have to. The goal here is to gain insight into how a totalitarian government operated.

The Rape of Bangladesh by Anthony Mascarenhas

In contrast to the biased and unsympathetic narration provided by Khadim Hussain Raja, we take a look at a book published in 1971 by another 'West Pakistani'—a journalist named Neville Anthony Mascarenhas. This book, The Rape of Bangladesh, provides a refreshingly honest retelling of the power struggles that set the liberation war in motion.

Anthony Mascarenhas is a journalist and author most famous for his exposé on the brutality of the Pakistani military during the 1971 Liberation War, an article that was critical in getting international attention and particularly in influencing India to move in with a stronger role.

The long report in The Sunday Times acts as a sort of unofficial prologue to The Rape of Bangladesh. The book starts with a background on what compelled Mascarenhas to write the original report. In April 1971, eight Pakistani reporters were given guided tours with the military in East Pakistan and instructed to spread propaganda, to declare that all was normal in East Pakistan. All but one of the reporters did as they were told—only Anthony Mascarenhas seemed so shaken by his experience that he had a moral crisis.

Yvonne Mascarenhas, Anthony's wife, recalled to the BBC in 2011: "I'd never seen my husband looking in such a state. He was absolutely shocked, stressed, upset and terribly emotional. He told me that if he couldn't write the story of what he'd seen he'd never be able to write another word again".

Once Mascarenhas' pitch was greenlit, he fled with his family to England and published the story from there, away from the strict government censorship in Pakistan.

In his book, Mascarenhas not only describes the West Pakistan-led genocide but also the geopolitical forces at play that culminated in the war. Pakistan had been described by Mascarenhas as a state with "built-in conflict"; several different identities—Bengalis, Baluchis, Sindhis, Pathans, etc.—had all been brought under the same country on the basis of religion alone. He identifies that one of the reasons the Pakistan government had been so afraid of East Pakistan's uprising was that it might inspire the other groups to do the same.

However, he points out, of all the different groups it was often East Pakistanis who were unfairly vilified. Mascarenhas lays out in simple yet gripping prose the fact that East Pakistan was continually oppressed and ignored both politically and economically to the extent that it made sense for the country to at least have provincial independence. While his imagery feels a little heavy handed at times, similar to the lens that many development workers use to depict rural poor Bangladesh today, there is an undeniable truth in the picture he paints. East Pakistanis were not living the comfortable, luxurious life that their western counterparts had been privileged to.

What makes Mascarenhas' book compelling is that he includes quotes from notable (though mostly unnamed) figures in the Pakistani military and government. As a West Pakistani citizen and reputed journalist, it is believable he had contact with editors with valuable intelligence and eager informants, and had spoken to military officers during his tour of East Pakistan. This is in addition to the relevant quotes and statistics from sources such as government white papers, press conferences, and books such as Rehman Sobhan's Bangladesh Economic Background and Prospects (Bangladesh Newsletter, 1971), Tariq Ali's Pakistan—Military Rule or People's Power? (Cape, 1970), and others. Mascarenhas begins each chapter with a quote, usually from key figures including but not limited to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Tajuddin Ahmad, and Yahya Khan, and then takes us through the events leading up to the massacre on 25 March 1971, outlining the slights and micro-aggressions against East Pakistan, the arrogance of the West Pakistan government prior to the election of 1971, and what he calls the "Post-Election Farce".

The narration of the events following the election are perhaps the most interesting—particularly as honest accounts of the Pakistani perspective on this issue are most often highly unreliable. With a majority win in assembly seats, it would be difficult for West Pakistan to influence the constitution if members of the Awami League were not on-board. Mascarenhas recreates a very convincing trail of the decisions that led Yahya Khan to postpone the inaugural session of the national assembly. As with the rest of the book, he draws out a timeline of important events during those few months to highlight the cunning political gambits that are often easy to miss when viewed in isolation.

In the chapter titled "Genocide", in a fitting throwback to the title the report that started his journey of documenting the war, Mascarenhas describes the events of Kal Ratri, 25 March, 1971. He keeps this section brief, but does not try to soften or sugar-coat the brutality of the war and the intentional cleansing of not only Hindus (as was the rhetoric used as justification by the West Pakistan military), but of the entire province of East Pakistan. The chapter touches upon the onslaught of attacks on Pilkhana, Rajarbagh, the offices of the pro-Awami League journal The People and the Bangla Daily Ittefaq, and on student accommodations at Dhaka University by tanks, bazookas, and automatic rifles. The terse writing of this section reflects the cold and systematic murder that took place that night and how each location had been pre-determined with military precision.

Mascarenhas' book, though short, provides an extremely exhaustive narrative account of the events leading up to 1971, supplemented by useful and important appendices. A reader already well-versed in the events and politics of the Liberation War might not find anything new, but personally, I was drawn to the validation it offers. It is a welcome change to find at least one West Pakistani who corroborated and confirmed the atrocities we have grown up hearing and reading about in Bangladesh, given that the more common narrative from the other side is often one of ignorance and denial—as recently as this week Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) mysteriously, and at the last minute, cancelled its online conference that would have commemorated the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh's Liberation War.

Rasha Jameel studies microbiology whilst pursuing her passion for writing. Reach her at rasha.jameel@outlook.com.

Selima Sara Kabir is a research associate at the BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, where she combines her love for reading, writing, and anthropological research.

Read this article online, on The Daily Star's website, on facebook.com/dailystarbooks, @thedailystarbooks on Instagram, and @DailyStarBooks on Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments