The unfortunate Asians of Uganda

In the 1890s, many South Asians were brought to Uganda by the British Empire for administration and development purposes. The Uganda Railway remains a timeless reminder of the South Asian workforce's contribution. Throughout the years, as the Asian population multiplied in the country, their domination in the economic sphere grew rapidly. Many native Ugandans turned resentful at the trend. "Indophobia" was on the rise. In 1972, after Idi Amin rose to power following a coup, he issued a decree requiring all Asians (80,000) to leave Uganda within 90 days, leaving their property and wealth behind.

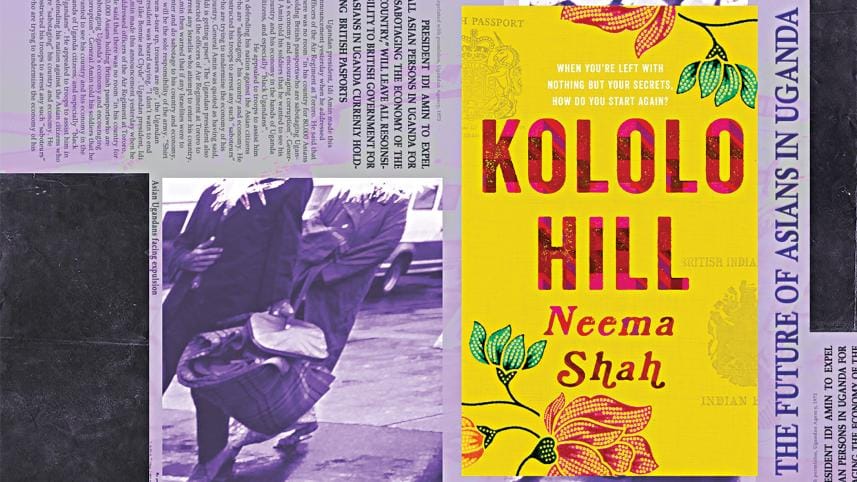

Neema Shah's debut novel, Kololo Hill (Picador, 2021), is set against this backdrop. Hers is a South Asian history which is rarely portrayed in art. I first became aware of the Asians' expulsion from Uganda after watching Mira Nair's film Mississippi Masala (1991) two years ago. I was delighted to hear about Kololo Hill's release given that it is a novel that illuminates this history.

Asha and Pran have been married for a few months when the decree is issued. They both grew up in Uganda, never stepping foot in India, their ancestral country. Pran's parents, Jaya and Motichand, are the only characters through whom we get glimpses of India and migration to Uganda in the novel. Pran and his brother Vijay have tirelessly worked to save the family business that Motichand started many years ago. President Idi Amin's decree at such a moment proves disconcerting for the family. What makes the prospect of leaving more difficult is the intimate and wholesome bond the family shares with December, their native Ugandan domestic help. He is a man from the predominantly Christian Acholi tribe, which is on Amin's execution list alongside the Lambi tribe. Moreover, being on friendly terms with Asians poses threats for native Ugandans.

Ethnic resentment is evident from the very first scene in the novel when Asha stumbles across a lake full of bodies. As the story progresses, we see how each character comes to terms with their grim reality. Curfews, segregation, soldiers' harassment, fear-laden conversations among friends and family, all mark the shared general experience of South Asians in Uganda of the time.

As they finally leave the country, memories, traumatic experiences, a terrible secret, and the trials and tribulations of starting a new life from scratch hang over the family. It is worth noting how all these factors shape the characters' arcs and make them memorable and alive in the reader's mind. For instance, back in Uganda we see Vijay as a subordinate figure to his brother. But in Britain, circumstances force him to take charge. Another element that brings some variety to the reading experience is the way all the chapters are arranged according to each character. Aside from Motichand and December, the rest are given enough space to make the novel a multi-protagonist narrative. In just 340 pages, we get a complete sense of each protagonist's struggles.

It was especially satisfying to find that the story divided equally between Uganda and Britain. The plot points in the first half explore political instability in Uganda while in the second half, we witness the characters forging new paths of life and the turbulent trajectory the lives of the many political migrants took then. For South Asian readers, the common cultural elements—from food items to rituals—blended with the knowledge that this is a culture undiminished by change in location, acts as a bonus. I particularly loved the solidarity between the South Asian and the Black community reflected through December's relationship with his employers.

Didactic descriptions of political affairs do not taint this novel. We get to know of the political scenario through its physical manifestations and the ways they affect the storyline, from disappearances to lootings and arbitrary arrests. The simple yet poetic prose reminded me of Jhumpa Lahiri's The Lowland (Knopf, 2013) and Tahmima Anam's The Bones of Grace (HarperCollins, 2016).

Shortlisted for the Bath Novel Award and the First Novel Prize, Kololo Hill is an essential and searing novel about xenophobia, racism, family, loss, migration, and colonialism's legacy across Asia and Africa.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments