Of Myths, Migrants and Misconceptions: A Personal Essay on Charges

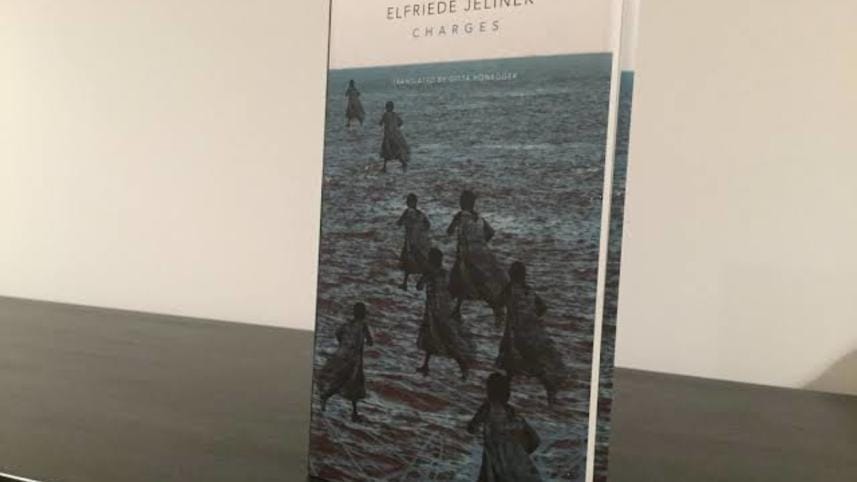

The Reading Circle (TRC) a book club in Dhaka, started the new year with a Literary Encounter at the Goethe Institut onSaturday, January 4. The book for discussion was Charges by Elfriede Jelinek.

Elfriede Jelinek, the Austrian novelist, won the Nobel prize for literature in 2004 and because I had not heard her name prior to that, I kept my eyes open for her books when I next visited a bookstore."Jelinek's work is brave, adventurous, witty, antagonistic and devastatingly right about the sorriness of human existence …her contempt is expressed with surprising chirpiness: it's a wild ride… wonderful, defiant mischief-making," the Guardian was quoted in the blurb.

I bought the book and put it on my shelf to read "one of those days."Other books by Jelinek took their place beside it – Wonderful Wonderful Times, Women As Lovers and Lust but despite the tantalizing titles three years flew by. Then one day TRC decided to tackle Charges by Elfriede Jelinek.

Initially I tried to read it blind, no introductions, no reviews, no comments.I wanted to "take a wild ride" enjoy the wit and "contempt ... expressed with surprising chirpiness…." Twenty pages into the book I had no idea what she was all about. "Defiant mischief-making" mocked me from my thought bubble.

The blurb said she had used Aeschylus' play The Suppliants as a source. I went to the source; reading just a few pages of that unraveled the setting for me.

Aeschylus' play The Suppliants (also known as The Suppliant Women or The Suppliant Maidens) is based on the myth of Danaus and his fifty daughters, collectively known as the Danaides, who flee from Egypt to Argoswith their father in an attempt to escape a forced marriage to their Egyptian cousins, the fifty sons of the usurping King Aegyptus, Danaus's twin brother.In Argos, Danaus and his daughters ask King Pelasgus for his protection and asylum. At first, he refuses, and says he needs to confer with the people of Argos. He is hesitant as the fleet of Egyptians is in hot pursuit of the Danaides. There is an attempt to force the women to return to Egypt but King Pelasgus and his army drive off the Egyptians and succeed in giving protection to the supplicants.

Charges, Elfriede Jelinek's play (Jelinek herself categorizes it as a play), is an artistic response to current events that were taking place in Austria at that time. Asylum seekers from Afghanistan and Pakistan, had marched from the initial reception center in Traiskiskirchen (Lower Austria) to Vienna and occupied Vienna's Votic church in 2012 as an act of symbolic sanctuary. Initially their request for protection was granted but later they were asked to move to an alternative venue, a monastery. This led to the Votive Church Refugee Protest.

After Jelinek had completed the 1st version of the text in June 2013, there was a devastating tragedy near Lampedusa, in which more than 300 boat refugees were killed. This led to a 2nd version. She wrote two further versions reflecting the changing situation. Her work turned out to be prophetic as events she described in her book ended up happening (bodies of 70 refugees who died of suffocation was discovered in a refrigerated truck somewhere between Hungary and Austria two years after the publication of her book). Later in 2015, two sequels, Appendix and Coda were tagged to the end by Jelinek.

We can see, therefore, that the Danaides, share a number of characteristics with present day refugees in general and the ones in Jelinek's text in particular:

1. In both the plays the chorus, instead of being a voice in the background, as was customary in the Greek plays, is also the protagonist or the main character.

2. In both the plays, the refugee chorus gives similar reasons for choosing to leave their homeland and seeking refuge from strangers. As the chorus in the Greek play says: "This exile is our own decision. We have fled a despicable situation." The present day refugees too "have fled a despicable situation." They speak of family members who have been murdered and their attempts to avoid the same fate for themselves. Some of the most heartrending parts of the chorus's speech are when they recount their grief and their woes and the endless indignity of their misfortunes: "After those monstrous killers back home … took everything from us, we should be able to get something…instead you call us a cursed, raging brood, brood, brood! Like animals! Brood of foreigners!"

3. Both the groups are caught in a "in-between space," a liminal space; the Danaides wait between the port and the city center and the present day refugees wait for an asylum decision.

4. Both the groups have escaped into the unknown.

5. The Danaides have crossed a body of water to come from Egypt to Argos. Many of the present day refugees have done the same. The Coda, added later, is all about crossing a body of water.

6. Given that Jelinek is using The Suppliants as her source for her book Charges, she adopts the narrative structure and setting of Aeschylus's play. There is a cyclical way of coming back to the same narrative in the Greek plays and we find that deliberately done in Charges. The setting of course is a group of refugees fleeing from their own land to unknown shores.

7. In Aeschylus's play the people of Argos are divided in their reception of the suppliants. They wish to do the right things, be hospitable to someone seeking their protection, but at the same time they are wary of confronting the Egyptian fleet. This is also true in Charges. The debate among the politicians and the citizens was basically this: humanitarian reason on one side and xenophobia on the other.

While politicians and the local people were debating on the course of action regarding these refugees, the Austrian government granted citizenship to a couple of privileged cultural figures (Boris Yeltsin's daughter, TatyanaYumesheva and a world-renowned Russian opera singer, Anna Netrobko). In her play Jelenik exposes the contradiction is the injustices in Europe's asylum system. Those with money or influence are welcomed but those who are poor and powerless are not.

Jelinek is undoubtedly a master wordsmith. The Nobel committee acknowledged this when they gave her the prize in Literature (2004) "for her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that with extraordinary linguistic zeal reveal the absurdity of society's clichés and their subjugating power".

This mastery spills over in her wordplay. Linguistic slippages litter the text. To pick out just a few:

• "No one looks down with mercy at our train, but everyone looks down on us."

• "We fled, not convicted by any court in the world, convicted by all, there and here."

• "They tell us nothing, we find out nothing."

• "…whom may we hand this, this pile, we filled two tons of paper with our writing, wehad help with that, of course, now we hold it up suppliantly, all that paper, no we don't have papers, only paper…" (she plays on the different uses of paper: as writing material and as document)

• "We lie on the cold stone floor, but this comes hot off the press…"

• "We don't have anyone's sponsorship," the protagonist laments, "the only ship we had was an old, sinking boat."

Usually, when I read a book in translation, a part of me wonders how the original reads and what I am missing. The translation by Gitta Honegger left me amazed at how flawlessly the linguistic devices (and the book abounds in these) have melded into the fabric of the text.

Jelinek's work has been described by her detractors as "whining, unenjoyable public pornography", as well as "a mass of text shovelled together without artistic structure" (Knut Ahnlund, former Nobel Academy member).

Admittedly, Charges reads like an interior monologue and has a stream-of-consciousness aspect about it. The description of "a mass of text shovelled together" is partially justified, but there is certainly an artistic structure to it. The lack of punctuation and connectives gives the language an urgency and a breathlessness. What an apt way to describe the voice of a body of people trapped together with nothing but water all around them. Who but an agrophobe (one who fears open or crowded places - and Jelinek has admitted to being one) can better describe the condition of people trapped in one place unable or lacking freedom to leave the designated place, a place they have not chosen?

The Greek dramatists used myths with moral, religious and philosophical meaning to teach one how to live a good life. Jelinek has employed the same medium to expose the desperate plight of the refugees and to give the message that they should be treated with dignity instead of disgust, while at the same time exposing the magnitude of the problem.

The number of people driven from their homes by war, persecution or terror has exceeded 65 million for the first time in United Nations history. Unfortunately, given the present political scenario the situation can only worsen.

Razia Sultana Khan is a writer and an academic.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments