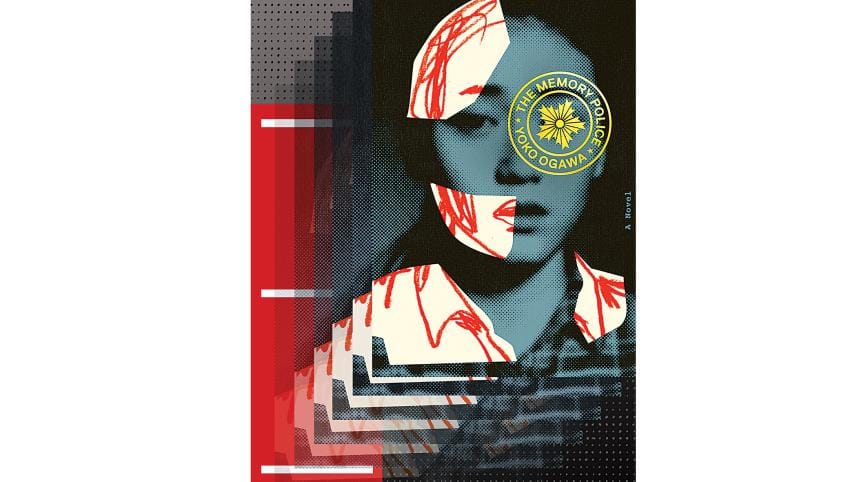

Humanity invites its degeneration in ‘The Memory Police’

On an unnamed island, the townspeople awaken to an unsettling feeling. Something has disappeared from their memories and dropped into a bottomless pit, joining perfume, hats, and birds, to name a few. From today, the townspeople are incapable of remembering anything about this 'something'.

Disappearing objects aren't what makes Yoko Ogawa's The Memory Police so dismal, though. Its true tragedy is about people giving up and giving in. Forgot about roses? Just gather all proof of them ever existing—photographs, poetry, petals pressed into a journal—and burn them to ashes or hurl them into the raging river. Pain does not exist in oblivion.

To maintain this ignorant fantasy—to 'help' the society—the island's authoritarian controllers, the Memory Police, enforce disappearances. They raid homes for illegally hidden objects, and arrest those immune to the erasing force.

Our unnamed protagonist's mother, who was murdered by the Memory Police, was one such disturbance. After realising that her editor, R, can also remember, our protagonist-novelist decides to hide him under the floorboards of her late father's office with the help of an old man she has known since infancy. R's memories are alive but her own are "sodden flower petals sinking into the waves or ashes at the bottom of the incinerator".

This remarkable work of Japanese literature sat undiscovered by the English-speaking world for 25 years before the 2019 translation by Steven Snyder. Ogawa, whose other translated works include The Housekeeper and the Professor, The Diving Pool and The Cafeteria in the Evening and a Pool in the Rain, has already won every major literary award in Japan. Floating through her gentle storytelling makes it easy to understand the acclaim.

Unlike fiction's traditional nature but like the world it describes, things escalate ever so slightly in Ogawa's novel. You sit at the final page dumbstruck at how things ended this way. This pace fits her narration of social detriment. By not questioning authority, by not staying alert, the townspeople have invited their own destruction, ignoring the chipping until everything was chipped away.

It would be easy to class this as political commentary, but Ogawa goes kilometres deeper. Even when R is locked away, he is more alive than our free-living novelist ever was. She goes to work, speaks with neighbours, but her functionality by no means proves her humanity. Her writing does. Towards the beginning of the novel, she and R share this exchange:

"It seems strange that you can still create something totally new like this – just from words – on an island where everything else is disappearing."

"And what will happen if words disappear?"

You see, things can fuse into one's identity and become boundless vehicles of expression over time. What if the pianist forgets how to play? What if the artist forgets about paint brushes? People are what they are in this book. So who would our novelist be without novels?

By detaching meaning from people and objects, Ogawa shows just how one-dimensional people can become without creativity, thought, and knowledge. To her, humanity is the boundless universe inside one's head—the birthplace of art, music, poetry, and human connection. This is where people thrive, and it is what Ogawa urges us to never loosen our grip on. Even if the world forces us to. Even if it means we must go underground.

Alifa Monjur is studying commerce and law in Sydney.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments