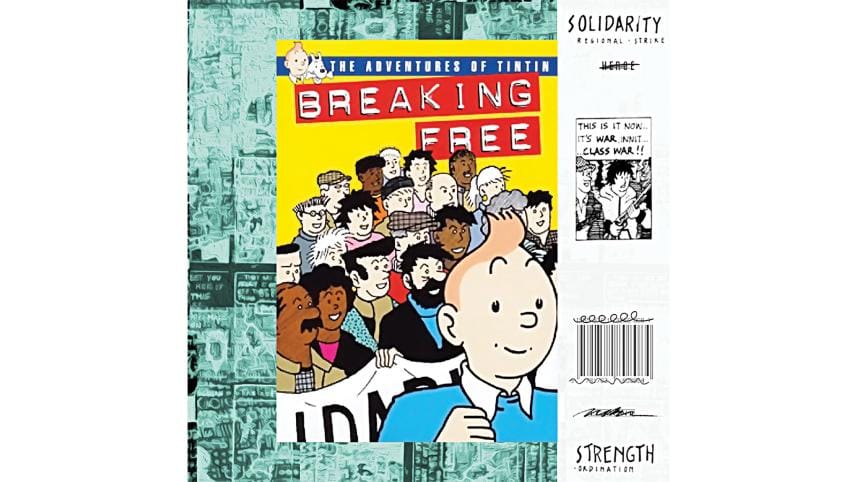

An anarchist retelling of Tintin

The globetrotting hero-reporter, he of the blonde quiff and the plus four trousers, had many an adventure throughout a 46-year-long run under the iconic ligne claire penmanship of his creator Hergé (the Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi). We've seen him canoeing down the Amazon, driving Atomic era tanks through the Eastern Bloc, and beating Neil Armstrong to the moon. Yet none of these settings feel as exotic to the character as the picket line of a worker's strike.

Tintin: Breaking Free (Attack International, 1988) was published in the UK at the tail end of the Thatcher years. Written by the pseudonymous J Daniels, it is a repudiation of the rapacious capitalist regime of the Tories in the wake of union-busting, industrial collapse, and the privatisation of the welfare state. The comic is an example of the leftist practice of "détournement", hijacking media to critique the very capitalism it was intended to support.

Every character, every pose in the comic is a recreation of an original Hergé drawing, completely recontextualised. Tintin here is no Belgian reporter: he's a working class lad (quite workshy and with little class) who begins the tale at the end of his tether, out of work and in trouble for shoplifting. With the help of his uncle the Captain (Haddock, though that name is never used and his colourful language and alcoholism are set aside) he finds work at a construction site. Rumblings of working class alienation, lack of social support, gentrification, the corruption of union bosses and the disunifying evils of homophobia and racism lead to a full-scale social upheaval when a worker at Tintin's construction site dies as a result of nonexistent safety measures.

What follows is an incredibly earnest exploration of building working class solidarity and of how to organise properly: picket lines, meals for the elderly, cooperative printing presses and strike coordination centres. There are violent clashes with the police, unlawful arrests and beatings, death threats and arson, but nothing that crushes what is implied by the final pages: an international revolution, and the coming of a new, better world. For the cynical reader unconvinced by socialism, it can be dry and maudlin. It was not written for the cynical reader.

In the best traditions of the Tintin stories, J Daniels took the character and placed him at the heart of contemporary issues; the ever-malleable, everyman reporter becomes a vehicle for the author's intent. Unlike Hergé, whose inauspicious beginnings saw Tintin spout anti-Bolshevik propaganda and justify the Belgian colonisation of the Congo before switching to more well-meaning racism in the service of critiquing the Japanese atrocities in pre-WWII China, Daniels' Tintin is no cipher or audience surrogate character. He's not fighting for the perpetuation of a status quo, or inserting himself into the business of hapless foreigners; Daniels' Tintin is protecting his own people at home and trying to carve out a better world for them.

Hergé may have tried to distance himself from his roots in right-wing, fascist media, but the later Tintin comics never truly rose out of that ideological pit. The popularity and staid worldview of the comics invite subversion. Tintin: Breaking Free is the most famous—and extensive—of a series of reworkings from the left. Interested readers should look up the raw, powerful one-pager The Adventures of Tintin in Patriarchy Is Our Prison, or The Adventures of Shrimptin on social media, whose admins have dedicated themselves to undermining Hergé's legacy through bizarre, barely comprehensible memes.

Zoheb Mashiur is a doctoral researcher on race and the British Empire. He is based at the University of Kent's Brussels School of International Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments