Fifty Khasi families in uncertainty

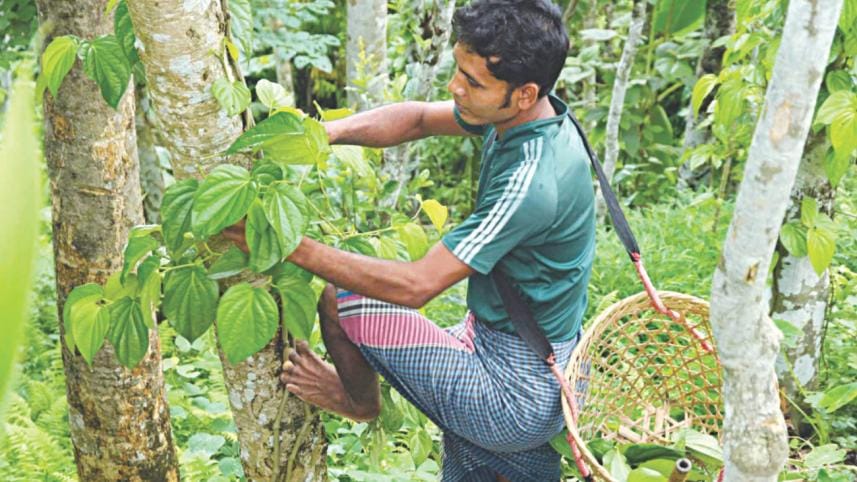

Welsi Amse has always dreamt that her children would become doctors one day. She has been squeezing every penny possible from the meagre earnings from a betel leaf garden at Pallathal Punji in Moulvibazar for the last few years.

But all her dreams have started to fade away after she came to know that her betel leaf garden, her only source of income, would soon be taken away. Now, the 35-year-old woman is worried sick over how she and her five-member family would survive if their land is taken.

Around 50 Khasi families living in Pallathal Punji (indigenous neighbourhood) in Moulvibazar's Baralekha upazila would lose their homestead once the exchange of the adversely possessed land, following the signing of the land boundary agreement, start happening.

Lukas Bahadur, headman of Pallathal Punji, told this correspondent that around 300 acres of land, where Khasis cultivate betel leaf, would be taken.

“Although India is erecting a barbed wire fence on its part along our betel leaf garden, our officials are not doing anything to stop them,” he alleged.

The betel leaf garden is the lone source of income for the 50 Khasi families comprising around 250 people. The families living at the hillocks in the upazila are passing days amid worry over losing the land they had been living on for centuries.

As part of the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement (LBA), Bangladesh will give India 2,777 acres of adversely possessed land and get 2,267 acres in exchange. The land is in the bordering areas of India's Assam, Tripura, Meghalaya, and West Bengal states.

The Pallathal area in Barlekha, bordering Assam and Meghalaya, consists of adversely possessed land. It includes 300 acres of homestead and cultivable land of the Khasi and Garo people.

Lukas Bahadur said, “Our land was excluded in the 1974 survey, but India claimed the land [more than 300 acres] in 2011. Now they are setting up a fence blocking the main entrance to the garden. I've already informed the local administration about this, but they refused to help us and said the order came from higher authorities.”

He claimed that this piece of land was never a part of India.

Villager Siang Bereh, 70, told this correspondent that it was better to die than to leave their homesteads.

“I want to die on my ancestral land. If the government does not understand the reality of the situation, what can we do? I would rather die than give up our ancestral land,” he said, with tears trickling down his cheeks.

Indigenous people, rights activists, politicians, and environmentalists demanded that the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) investigate the matter and submit a report to the government, he added.

Contacted, Ehsanul Haque Kabir, surveyor of the Pallathal border area, said it was the decision of the higher authorities.

Sanjeeb Drong, general secretary of Bangladesh Adivasi Forum, said though the LBA spoke of thorough consultation with the people affected before drafting the agreement, officials of neither country talked to the Khasi people of Pallathal.

A high level committee comprising representatives of the government and the civil society should immediately visit the Pallathal Punji, he said.

Sanjeeb demanded that a state level dialogue between high officials of two countries be held to address the issue.

“The Khasi and the Garo people want to stay in their own land. They do not know about the agreement and neither are they aware that their cultivable land would be under Indian possession,” he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments