Time to support and reskill domestic workers

Amid the ongoing restrictions meant to reduce the transmission of Covid-19, 32-year-old Nasima Begum, living with her husband and two sons in a Hazaribagh slum, has been finding it very difficult to make ends meet.

14 July 2021, 18:00 PM

Online skills training for women: more caveats than what meets the eye

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been nominated as one of the top three women leaders who tackled the Covid-19 crisis well. While her efforts to bring Bangladesh into the limelight has been highly appreciated, addressing gender gaps remains a challenge that needs attention, not only through policy adjustments but also by getting down to the nitty-gritty where real challenges lie for ordinary women.

15 March 2021, 18:00 PM

Is the government doing enough for small firms?

Sadat Rahman (not his real name) has a small photocopy shop right beside a renowned university in Rongpur.

12 February 2021, 18:00 PM

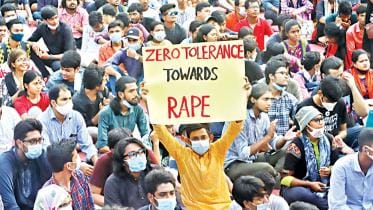

Protests against rape give us hope. But is that enough?

After the video of the Noakhali gang rape went viral, people from all walks of life were rightly outraged and joined online and offline protests demanding reforms in the relevant law against women and children repression as well as the highest punishment for rapists.

14 October 2020, 18:00 PM

The long and winding road to end discrimination against women

It has been 41 years since the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted. Bangladesh ratified CEDAW in 1984 but with reservations about certain articles that uphold a state’s responsibility towards women and their right to social and economic advantages, and address discrimination in matrimonial and family laws.

2 September 2020, 18:00 PM

World Youth Skills Day: “Skills for a resilient youth” will require connectivity and a resilient mind

This year, the World Youth Skills Day takes place at a challenging time, when the need for skills is higher than ever.

14 July 2020, 18:00 PM

Work from home: More cons than pros

While personally I found more positives than negatives in working from home, I realise that the sudden shift to full-time online work may have affected others differently.

11 June 2020, 18:00 PM

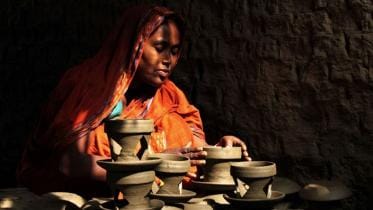

What does Nurjahan need?

I was talking to my household care worker; i.e. domestic worker, Nurjahan (not her real name). A person who can do it all—not only does she cook and clean, she does groceries when needed, waters my plants, feeds my cat and gives me immense mental support when I’m down.

11 May 2020, 18:00 PM

Are we really aware of the challenges the youth face?

One in three of Bangladesh’s 170 million people is aged between 10 and 24 years, and the country is well in place to reap the benefits of this demographic dividend; or so we hear.

17 August 2019, 18:00 PM

Changing how we see vocational education

Bangladesh has gone through both social and cultural changes during the past two decades. Things were very different for the youth in the 1990s compared to now.

27 September 2018, 18:00 PM