Improving the Human Development Index: The Bangladesh perspective

People are the real wealth of a nation. The fundamental objective of development is to create an enabling environment for people to enjoy a long, healthy, and creative life. Human development is simply defined as a process of enlarging choices and creating opportunities for everyone. In the ultimate analysis, human development is the development of the people, development for the people, and development by the people. The human development framework has also introduced a composite index—the Human Development Index (HDI) for assessing achievements in basic dimensions of human development. It consists of three basic dimensions of human development—a long and healthy life, measured by life expectancy at birth; knowledge, measured by mean years of schooling and expected years of schooling; and a decent standard of living, measured by gross national income per capita. The theoretical maximum value of the HDI is 1.0.

Over the years, Bangladesh has made tremendous progress on economic and human development fronts, as measured by the HDI. From 1990 to 2019, Bangladesh's HDI improved from 0.394 to 0.632 – a nearly three-fifth increase. In fact, with China leading the race, Bangladesh is one of the top five countries in terms of the largest absolute gains in the HDI score during that period. Over the last 30 years, Bangladesh has moved to the medium human development category from the low human development category.

And on many human development fronts, its progress has been better than its neighbors. Bangladesh has achieved a life expectancy at birth of nearly 73 years, compared to nearly 70 years in India and 67 years in Pakistan. In 2019, the under-5 mortality rate per 1,000 live births was 31 in Bangladesh, 34 in India, and 67 in Pakistan respectively. Its mean years of schooling at 6.2 years is better than that of Pakistan (5.2 years) and Nepal (5.0 years).

When the male and female HDI of Bangladesh are compared, in 2019, while the HDI value for women in Bangladesh was 0.596, that of men was 0.660. The overall Gender Development Index (GDI) score for Bangladesh in 2019 was 0.904, higher than those of India (0.820) and Pakistan (0.745). Even though both Bangladesh and India started from the same GDI score (0.702) in 1995, by 2019, Bangladesh surpassed India, reflecting better progress in gender equality in human development, as measured by GDI.

The potential gains in human development are sometimes lost because of existing socio-economic inequalities. When measured by the income-inequality adjusted HDI (IHDI), Bangladesh loses 24 percent of its overall HDI. However, the good news is that during the last decade (2010-2019), the IHDI value of Bangladesh increased from 0.387 to 0.478, implying that inequality in human development declined during that period.

On the health front also, Bangladesh has made notable progress. During the last three decades, (1990-2019), Bangladesh reduced its infant mortality rate from nearly 100 per 1,000 live births to just 21 per 1,000 live births: the maternal mortality rate from 165 per 100,000 live births, down from 594 deaths per 100,000 live births. The country has also fared better in child immunization. The diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) immunization rate now cover 98 percent of children aged 12-23 months. The situation of child nutrition has improved substantially in Bangladesh. During the period 1990-2019, the prevalence of stunting in children declined from 55 percent to 28 percent, and the incidence of underweight children reduced from 56 percent to 22.8 percent. Over the years, Bangladesh has successfully reduced its total fertility rate (TFR) from 4.5 births in 1990 to 2.04 births in 2019.

The country has also made notable progress in the area of education. The adult literacy rate in the country has improved to 74 percent in 2018 from just 35 percent in 1990. Between 1990 and 2019, the net primary enrolment rose from 75 percent to 97 percent, and the secondary enrolment up from less than 20 percent to 66 percent. One remarkable progress has been in female secondary education enrolment and in that indicator, Bangladesh has done better than countries like India and Pakistan. One of the major achievements in education is reducing the drop-out rates from around 50 percent in 2005 to below 18 percent in 2019.

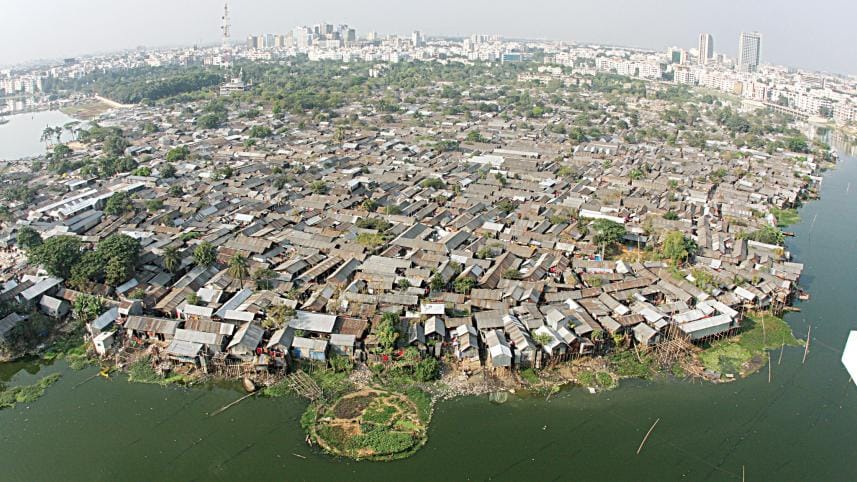

Even though over the past 50 years, Bangladesh has made impressive progress in overall human development, the achievements have been uneven across several planes – socio-economic groups, regions, gender, and rural-urban divide, and so on. Such disparities are also prominent in various human development areas. Thus, in 2019, while 85 percent of the babies born to the richest 20 percent of the population were delivered by a skilled professional, the corresponding figure for the poorest quintile is only 32 percent. The same year, the literacy rate for the population aged 7 years and more was about 75 percent in Barisal, but only 60 percent in Sylhet. In 2019, the mean years of schooling among girls in Bangladesh was slightly over 4 years, but that of boys was 6 years.

Like any other country, Bangladesh also experiences gender disparities in human development. Even though gender parity has been achieved in primary and secondary level enrolment, drop-out rates remain higher for girls than boys. At the tertiary level of education, the female rate of enrolment in 2017 was 17 percent, as opposed to 24 percent for their male counterparts. The female labor force participation rate in the country is only 36 percent, while that of males is 81 percent. The women's share of employment in senior and middle management was just about 12 percent in 2017.

Even with all the phenomenal human progress over the years, Bangladesh still faces several human development challenges. Some of the challenges represent lingering challenges, like poverty; some deepening challenges, like climate change; and some emerging challenges like pandemics.

In terms of lingering challenges, over the years, Bangladesh has been able to quantitatively expand its basic social services, yet the quality of such services has remained a lingering concern. This is true of health and educational services. Thus, expansions of services in many cases have been achieved with qualitative compromises. Given the current situation and the projected demographic dividend till 2030, ensuring jobs for people, particularly young people remain a lingering challenge. Over the years, even though remarkable progress has been made in the area of women's empowerment, women still face several deprivations. About 58 percent of women face domestic violence by their intimate partners. Furthermore, for every 100 unemployed male youths, there are 150 female youths. Of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) graduates, only 8 percent are women. One in every three women does not have access to financial institutions with mobile banking services.

In terms of deepening challenges, inequality has become the defining issue of the Bangladeshi society. In Bangladesh,the Gini index of income, a measure of income inequality, has increased from 0.39 in the early 1990s to 0.48 in 2016, suggesting an increasingly uneven income distribution over time. But the inequalities have also expanded in non-income areas, such as health, education, ownership of natural resources, etc. as well. Furthermore, there are inequalities not only in terms of outcomes but also in terms of opportunities – opportunities in health and education, as well as in productive resources, such as credit. Climate change-induced extreme weather events are estimated to have caused an estimated yearly loss of GDP of $1.7 billion. Loss of arable lands and livelihoods, displacement of people, loss of agricultural production, and food insecurity are caused by an increased frequency and intensity of various natural disasters, induced by climate change. In the ultimate analysis, climate change is not only an environmental challenge, but it has become a deepening human development challenge for Bangladesh. The issue of governance, efficiency, and effectiveness of the institutional structure of Bangladesh remains a deepening challenge.

In terms of emerging challenges, the Covid-19 pandemic has posed an unprecedented human development crisis for Bangladesh. In the future, pandemics may appear as another emerging challenge. The global economic system has become more fragile and inward-looking because of the COVID-19 pandemic, global conflicts, and extreme nationalism. Bangladesh may adversely be affected by these emerging challenges. Similarly, while we celebrate the graduation of Bangladesh from a low-income country into a middle-income country, we should also be aware and mindful of its implications – lesser tariff advantages; higher imports, increased non-concessional laid or grant. These would be emerging challenges for enhancing human development in Bangladesh.

In conclusion, human development for everyone in Bangladesh is not a dream, but a reality. In January 1972, while he was returning from his captivity to an independent Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman described his homecoming as a journey from darkness to light, from captivity to freedom, from desolation to hope. Today, hopes are within the reach of Bangladesh to realize. The nation can build what has been achieved and can attain what once seemed unattainable. For days to come, the country will ensure a journey from deprivation to prosperity, from challenges to opportunities, from ideas to actions. And in this journey, if those who are the farthest behind are reached first, noone will be left behind.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments