From digital to smart: Bangladesh on the growth path

That Bangladesh is a growth superstar of Asia looms large in any global economic forum, be it the World Economic Forum or the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. This sustained growth has been largely fuelled by the government's unapologetic push for digitising all government services to citizens, building an ecosystem for technology startups and incentivising the ICT services industry over the last decade and a half.

Leading up to the national elections of 2008, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's Vision 2021 laid out the roadmap to a dream—the dream of a Bangladesh that was an echo of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's utopic Shonar Bangla,a Bangladesh that was thriving, literate, connected, and empowered. A key rallying motto of this vision was the promise of a "Digital Bangladesh", which established a narrative of digitally supported socioeconomic growth. According to an e-government master plan for Digital Bangladesh published by the Bangladesh Computer Council (BCC), which is a government organisation operating under the auspices of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Division, this growth narrative was going to be bolstered by four interconnected and symbiotic pillars—digital government, human resource development, connecting citizens, and the promotion of the ICT Industry. For many, this promise was a panacea for many economic ills—the initiatives laid out by the government would be a harbinger for a better Bangladesh.

Others criticised what they deemed an unrealistic and misleading digital utopianistic view, especially in a country where digital penetration, literacy, and connectivity were still in its fledgling states. In the decade and a half since its conception, the term and the promise of Digital Bangladesh has been celebrated, memefied, consecrated, and upbraided, often concurrently and by the same group of people. Regardless of public reaction and perception, Bangladesh has progressed dramatically in its efforts to drive growth through digitisation and the implementation of emergent technologies. As we step into 2024 and are well on our way to the promised land of a Smart Bangladesh as detailed by the government's Vision 2041, how has the journey of digitisation factored into the multifaceted growth in Bangladesh? To what extent has the promise of a Digital Bangladesh been fulfilled?

Although petty corruption, bureaucratic red tape, and the glacial pace at which services are provided in many government sectors remain largely a staple in most circumstances, progress has been made to digitise various processes at a central government level. Services that were previously frustratingly on-site have gradually made a transition online. These include, but are not limited to, e-Passport registration from the Department of Immigration and Passports, construction permits of Rajuk, import permits by the Office of the Chief Controller of Imports & Export (CCI&E), investment registrations by the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), and land title mutation by AC Land Offices. These changes have also improved Bangladesh's ranking in the World Bank's "Ease of Doing Business Index". Government agencies have also adopted various digital tools in order to transmit and resolve internal tasks and communication. Examples of these electronic tools include D-Nothi, a digital filing system that is used to send and file internal communication by government agencies, and the Integrated Budget and Accounting System (iBAS++), which is implemented in resolving the salaries of government service holders.

As a result of various digital tools, the disbursement of public service salaries and pensions in Bangladesh have mostly transitioned to electronic platforms. Most, if not all agencies, now have some form of established online presence and digital footprint, which, at least in theory, removes a certain aura of inaccessibility that these organisations either deliberately or inadvertently used to foster. In certain regards, we have caught up to the other developing and developed countries in terms of consolidated services that are rightfully available to citizens from every economic stratum. On December 12, 2017, the national emergency hotline was officially launched which has, since its inception, maintained a very active Facebook page that chronicles the various successful rescue activities facilitated by the service. This type of contextual framing of an easily accessible state service as a force for general good is exactly the type of communication that the government should emphasise, and these positive changes were buoyed by a concerted push for centralised digitisation.

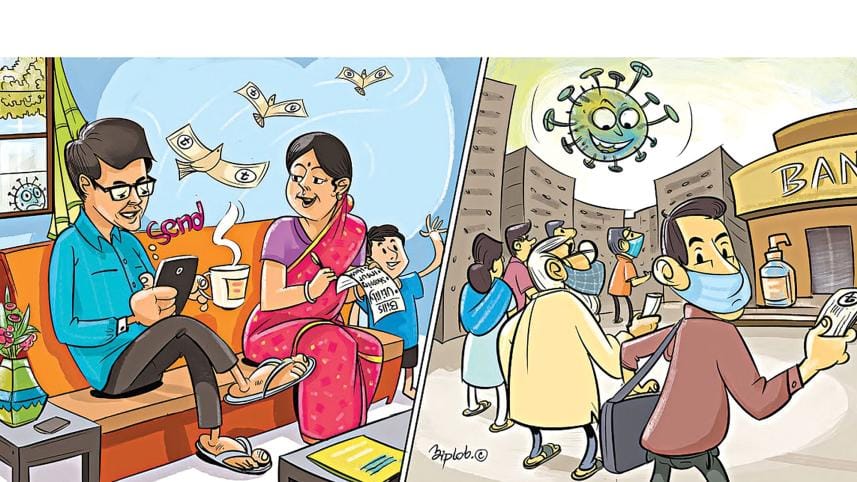

Digitisation and the adoption of technology has almost completely altered the landscape in the financial and entrepreneurial sectors. A large part of this change was driven by the meteoric growth and adoption of Mobile Financial Services (MFS) such as Bkash, Rocket, Nagad, and Upay. As a large part of Bangladesh's rural population are still not part of the banked and institutionally supported economy, the use of these MFS has brought a significant segment of the population into the digital fold. Transactions that would have previously been subject to lengthy and tedious procedures and potential harm from scammers have now become seamless due to mobile banking. MFS and other similar services have also significantly bridged the gap between urban and rural spaces, as the transfer of information and funds can now be easily facilitated.

These digital conveniences are also no longer the realm of tech savvy youth groups, as even older and digitally illiterate people can use these services with relative ease all with the use of their own cell phones or authorised local agents.

Private companies like ShopUp, Mokam, and REDX have facilitated the growth and ease of management for various small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh, working with businesses such as a neighbourhood general store to a small-scale private boutique to help them expand and build a sustainable future. These changes to the digital environment mean that a stall owner in a rural village or a CNG driver in a suburban city in Bangladesh now has access to services and digital facilities that, even a decade ago, was accessible by members of the highest echelon of society. On a larger statewide scale, the government has also set into motion various incentives and tax-exemptions for the IT service sector, although the efficacy and long-term benefits of these initiatives have been brought into question by entrepreneurs and other prominent figures in the industry.

Digitisation has perhaps been most successful in spheres where it has been able to successfully market and sell convenience. Be it online shopping, ride sharing apps, or food delivery services, people with disposable income have regularly prioritised their time and convenience at the cost of extra charges and fees. Online marketplaces such as Daraz, Bikroy, Othoba, and Pickaboo give their users centralised repositories of products that they can access through a simple search, and which will be delivered to their doorsteps. Ride sharing services such as Uber, Pathao, and Obhai remove the hassle of finding, hailing, and bargaining with ride providers from the equation of the daily commute. These services also provide a plethora of options from the type, size, and make of the vehicle. Food delivery services like Foodpanda and HungryNaki allow users to peruse the menu of thousands of restaurants with varied cuisines before they make their decision and their food is delivered to them. Rather than people suffering from a lack of choices and options, people today must contend with choice overload and analysis paralysis.

Some of these services of convenience became services of necessity during the last few years, as the world stood still, cowering and isolated due to a global pandemic. As covid-19 ravaged populations in every continent of the world, Bangladesh went into a general lockdown on March 23, 2020. General lockdowns of various lengths were further imposed in October 2020 and April 2021, as vaccines slowed down but were not completely able to arrest the spread and mutation of the deadly virus. The first few months of the lockdown were trepidatious, as people grappled with something they had never encountered before. Gradually, as people realised that this was not a short-time inconvenience, but would rather affect them for years to come, alternative methods of communicating and conducting affairs were implemented.

The appearance of Blockchain Olympiad Bangladesh as a champion of online happenstance, right when the country experienced its first ever pandemic lockdown in March 2020, showed the early adopters how everything that seemed impossible without physical presence suddenly became not only possible but even a welcome relief. The very first Blockchain Olympiad 2020 was held fully online, including submissions, adjudications and award-giving, between March and May 2020 that engaged hundreds of university students, dozens of jurors and a handful of organisers paving the way for undeterred online work culture during the pandemic that has continued even afterwards.

Educational institutions became habituated to video conferencing and ed-tech to conduct classes and assessments. Many universities created or licensed personalised online learning platforms that eased the transition to online classes and assessments for both teachers and students. Video conferencing and online meeting tools such as Zoom, Google Meet, and Skype became mainstays for almost all enterprises and organisations for basic communication. The pandemic accelerated adoption of various technologies led to the burgeoning growth of various digital sectors. According to e-Commerce Association of Bangladesh (e-CAB) vice president Sahab Uddin, the e-commerce market nearly doubled during the pandemic to Tk 160 billion (USD 1.86 billion). Companies attempted to capitalise on the needs presented by people's unique circumstances during the pandemic, and provided new services such as home delivered groceries, telehealth, mental health support, and virtual events such as concerts. It is yet to be seen whether this accelerated adoption slowly wanes with time, or if it will act as a launching pad for further spurts of growth.

Bangladesh's next goal is to become a "smart" country, the blueprint of which has been laid out in "Making Vision 2041 a Reality: Perspective Plan of Bangladesh 2021-2041" manifesto, published by the General Economics Division (GED), Bangladesh Planning Commission, Ministry of Planning. According to Vision 2041, there are four basic pillars in attempting to build a smart Bangladesh, which are in many ways a continuation of the principles espoused by the Digital Bangladesh initiative. These are: (i) Developing human resources ready for the 21st century; (ii) Connecting citizens in ways most meaningful to them; (iii) Taking services to citizens' doorsteps; and (iv) Making the private sector and market more productive and competitive through the use of digital technology. A key aspect of the Smart Bangladesh movement is to prepare for emerging and nascent technologies such as artificial intelligence, automation, distributed ledger or blockchain, quantum computing, virtual and augmented reality, and 3D printing, which have the potential to drastically disrupt people's lives and livelihoods. The Smart Bangladesh initiative aims to leverage and utilise the transformative products of the fourth industrial revolution to create more opportunities to ameliorate potential loss of employment. Vision 2041 lays out the groundwork for Bangladesh to take advantage of innovation and digital opportunities to attain higher growth acceleration to reach upper-middle-income status by 2031 and to reach the advanced economy status by 2041. If we are successful in tapping into emerging technological and geopolitical trends, there is seemingly unlimited potential to unlock new frontiers for growth and expansion.

However, the biggest thrust under the Digital Bangladesh programme and the current Smart Bangladesh initiative is none other than democratising access to citizen services and financial inclusion. For more than a century, conventional banking has inched its way up-to serving around a tenth of the adult population. The advent of mobile financial services in the last 15 years has raised that to more than a third of the adult population. But unless a majority of the adult population comes under the banking ecosystem, financial inclusion will simply remain an elusive policy paradigm. In that context, the bold decision of the central bank to introduce digital banks under a new licensing regime in June 2023 is a huge historical milestone. The central bank expects that the new-fangled digital banks, the first two of which are Kori and Nagad, will push the envelope of financial inclusion and raise the bar on cashless transactions to nearly two-thirds before the end of the decade.

In this bold new venture and tryst with technology-centric destiny, the nation must steer clear of cybersecurity quagmires and make all out efforts to narrow the digital divides between geographies, demographies and educational attainments.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments