ICTs bringing new dimensions of service delivery

ICTs have dramatically changed service models in the last two decades. Many jobs have been made more efficient and less time-consuming using the power of technology. For example, we can now skip travel agents and choose our own adventures using online booking sites, and compare offers easily.

But, for some matters, we rely on experts such as physicians, veterinarians and lawyers. When our lives, our livelihoods, our companions or our rights are at stake, no one wants to take chances. Unfortunately in many developing countries there aren't enough experts to go around. It takes significant time and resources to become an expert. A country like Bangladesh, for example, experiences significant brain drain with many of the best and brightest choosing to take their talents to places where they will receive a higher financial return on their investments. The experts that choose to remain are mostly contained within urban or semi-urban hubs.

In some situations like brain surgery or a complicated international land dispute, there is no replacement for an expert, but more generally, some of the less specialised functions that experts serve can sometimes be decentralised. Within health professions for example, roles such as general physicians, are more prone to being decentralised using the power of ICTs.

Tele-service applications can help connect individuals in remote areas to experts who live and work in distant cities. An intermediary such as a paramedic or a rural medical practitioner can physically systematically capture the symptoms of a patient accompanied by high resolution photos and send to a doctor using mobile network. The doctor can look at the patient record and get back with a prescription or recommendations for lab examinations. While this process will definitely not solve all medical problems, it can definitely address some concerns, while saving a rural patient from a trip to the nearest city or exploitation by middlemen.

This service model is not only relevant for health but also for agriculture, veterinary and can be extended to any service that requires expert advice.

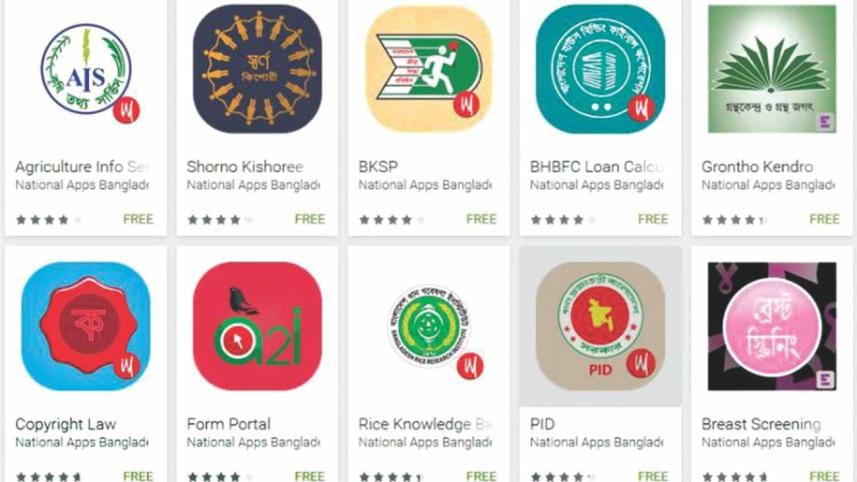

Proliferation of smartphones is also opening another vista of possibilities. Automated diagnostic applications on smartphones can help even low-literacy populations receive advice on how to address situations they are unsure about. For example, a rural chilli farmer whose crop stops producing fruit can use a mobile app that asks photo-based questions and generates a diagnosis and recommendation for how to address the crop issue. Depending on the content that is integrated, applications can also act as aids to workers such as pharmacists, physiotherapists and community health workers with intermediate levels of training.

Like any service that truly adds value to the community it is provided in, these models of technology-enabled service provision can be monetised to ensure sustainability as well as accountability to the actual needs and desires of customers. Such business models are driven by the community rather than being dependent on availability of uncertain and temporary donor funds that also sometimes come with undesirable conditions.

ICTs thus have the capacity to not only fundamentally change the way we think about delivery of expert services but also in creating entrepreneurs at the community level, who can serve as the eyes and ears of experts. With growing connectivity and smartphone penetration, new ICTs will become more and more relevant as a tool for the masses to access much needed services.

The writers work for a social enterprise called mPower, which designs and develops ICT-based solutions for the development sector.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments