| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 13 | April 01, 2011 | |

|

|

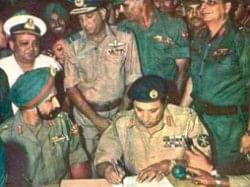

Musings ‘I am President of Pakistan . . .’ Syed Badrul Ahsan It is proper to go back to a recapitulation of history – of the state of Pakistan immediately after the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971. As Bengalis celebrated the surrender of the Pakistan occupation forces in Dhaka on December 16, a state of gloom descended on what had been till then West Pakistan and was now all that remained of Pakistan. State television for sometime flashed images of what was described as the fall of Dhaka. General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, who had told the world media at the Dhaka Intercontinental (today’s Sheraton) that the city could only be taken over his dead body, was shown signing the instrument of surrender before General Jagjit Singh Aurora, commander of the Indo-Bangladesh Joint Command. For Pakistanis, such scenes were unimaginable. In the months since hostilities had erupted between their army and the Bengali population of East Pakistan, they had been led to believe that first Tikka Khan and then Niazi had been squarely beating the Bengalis at any and every game. When India entered the war on December 3, it was given out all across West Pakistan that the Hindus (and that was how most people in West Pakistan looked down on India, from a communal perspective) were about to lose the war with their braver and far superior Muslim enemies. The shock, therefore, at knowing that East Pakistan was now Bangladesh and that the streets of Dhaka pulsated with cheering Bengalis celebrating the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army was immense. Many broke down in tears.

No one in the Pakistani military regime appeared before the country on December 16 to report on the calamity that had overtaken the army in Bangladesh. And Pakistan Television, after initially showing images of the surrender in Dhaka, clamped a ban on any further display of such footage. Across Pakistan, in Peshawar, Quetta and Karachi, protestors demanded the trial of the leaders of the junta. The next day, December 17, the Indian government called an end to hostilities on the western front, sending a wave of relief all over Pakistan. Rump Pakistan, after all, would not be broken into further pieces. The same day, late in the evening, President Yahya Khan spoke to Pakistanis over radio and television and showed no contrition over the way events had turned out for the Pakistan army in Bangladesh. He vowed to go on waging a war against the enemy until final victory had been achieved by Pakistan. In the four days between December 16 and December 20, Pakistanis in general and young military officers in particular made it clear that they wanted Yahya Khan and his regime to go. At one point, General Abdul Hamid Khan, chief of general staff of the Pakistan army, called a meeting of army officers in Rawalpindi cantonment and attempted explaining the causes behind the debacle in Bangladesh. He was greeted with expletives and eventually was forced to leave the room. President Yahya Khan was informed in no uncertain terms that he had to go. Evidently, at that point, the one man who mattered was Bhutto, then in New York, having presented the case for Pakistan as his country’s new deputy prime minister and foreign minister. For his part, Bhutto assessed conditions from afar and would not return until he was certain he could feel safe in Pakistan.

Bhutto arrived back in Rawalpindi around noon on December 20 and was immediately whisked away to the president’s house for a meeting with General Yahya Khan. He emerged a few hours later, as Pakistan’s new president and incongruously, chief martial law administrator. Late in the evening, President Bhutto addressed the nation and in a rambling speech promised his people that he would build a new Pakistan for them. He extolled the bravery of Pakistan’s soldiers in the just concluded war and asked forgiveness of his ‘brothers and sisters’ in ‘East Pakistan’. He showed absolutely no contrition over his role in the making of the crisis in Bangladesh but appeared keen to reassure Pakistanis that their future was safe in his hands. He placed Yahya Khan under house arrest and appointed new chiefs of staff for the army, air force and navy. Two days later, on December 22, as Bangladesh’s provisional government arrived in Dhaka from exile, Bhutto decreed that detained Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman be moved from solitary confinement in prison to house arrest. Mujib, who had declared Bangladesh’s independence in March before his arrest by the Pakistan army, had been tried before a secret military tribunal in Lyallpur and sentenced to death on charges of treason. He and Bhutto had not met since the army crackdown in Dhaka, but on December 27, Pakistan’s new leader arrived at the rest house where Mujib had been moved. As the Indian journalist Kuldip Nayar would later report in his book, ‘Distant Neighbours: A Tale of the Subcontinent’, a surprised Mujib asked Bhutto: “Bhutto, how are you here?” Bhutto’s response did not fit the question: “I am President of Pakistan.” An even more surprised Mujib teased him: “But you know that position belongs to me.” He was evidently referring to the Awami League’s victory at the general elections of a year earlier. This time Bhutto told him: “I am also chief martial law administrator.” In the next hour or so, Bhutto gave Mujib to understand that the Indian army had occupied ‘East Pakistan’ and that the two men needed to be together in the coming struggle to drive the Indians off. Mujib, ever the astute politician, knew better. It was a cold dawn on January 8, 1972, as President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto accompanied Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to Chaklala airport. As the plane carrying Bangladesh’s founding father to freedom flew off into the dark and towards London, Bhutto said to no one in particular, “The nightingale has flown.” Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |