| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue| 15 | April 13, 2012 | |

|

|

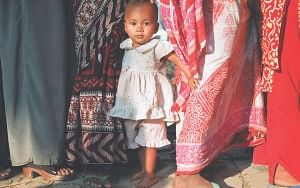

Special Feature The Working Mother Sushmita S Preetha A few months ago, a member of the European Parliament was photographed raising her hand in a vote in Parliament with a small baby strapped to her front. The heart-warming image evoked the harmony between the MEP's roles as a young mother and working woman. Contrast this with an equally poignant image of an earth labourer toiling at a construction site with a child strapped to her back. The mother, a young woman of about 27 years of age, takes a small break after an arduous morning to feed her three-month-old daughter.

As soon as she returns to her station, the manager of the site tells her off and forbids her from bringing the child to work again. “This is a workplace, don't forget. I'm not paying you to take frequent breaks. Plus, I can't pay the damages if something falls on her and injures her. You better leave her somewhere else tomorrow or don't come at all,” asserts the manager. Bewildered and scared, she looks at the other women for support. They shrug as if to say, “This is life. Suck it up.” It was nothing short of desperation that had led her to take up this job. She used to be a permanent worker at a manufacturing and processing unit until she was replaced when she became pregnant. Is motherhood a curse, she wonders, or a luxury? Unfortunately, Nasima's story is not an isolated case, but forms part of a larger pattern of discrimination against women in the workplace. An overwhelming majority of women working in different sectors have to face severe barriers that limit and undervalue their participation in the workforce. Many women are denied even the basic entitlement of a maternity leave, even though the law clearly states that women employees are entitled to at least four months leave in the case of private sector employees and six months in the case of public servants. According to the Bangladesh Labour Act 2006, an employer is bound to provide a total of 16 weeks before and after delivery. In addition, every woman is entitled to a maternity benefit equivalent to her four months' salary, twice during the tenure of her services as long as she has been working with the employer for six months. However, many women working in the private sector, especially those in the garments industry and in low-paying labour-intensive jobs, are not aware of their maternity related rights. Even when they do know, in the absence of strong unions and for fear of repercussions, they can't do much to protest. The Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights reports that an estimated 90 percent of the 3,870 export oriented garment factories in Bangladesh violate women's legal right to full paid maternity leave. Some companies harass women and pressurise them to quit, as in the case of Nasima. Some women are given the leave, but are asked to join as new employees when they return. Jui Nahar, a garment worker says, “I was very happy when they granted me my leave because they had previously denied it to a lot of my co-workers. But when I came back after three months, they told me to start as a beginner even though I've been working in this factory for the last six years. It means I'll only get paid the basic minimum as wage now.”

Her co-worker, Asma, says she had to quit when she could no longer work the insane hours that were required from her. “I was verbally harassed every time I asked for a sick leave or if I took frequent breaks on some days because I felt nauseous; after a while, I just couldn't handle the long hours and the strenuous activities,” she remembers. Many women in her position have no choice but to do overtime and partake in demanding tasks or work during the final stages of her pregnancy, putting both their own health and that of their child at risk. These factories, therefore, clearly violate the Labour Law Act which states that no employer shall employ a pregnant woman for “doing any work which is of an arduous nature or which involves long hours of standing or which is likely to adversely affect her.” Employers shy away from providing a humane work environment and basic benefits because it increases their costs. “In order for us to remain competitive in the world market, we have to cut costs,” admits a factory-owner who wishes to remain unnamed. “We would like to give all our workers maternity leave and benefits, as well as sick leave, but the simple truth is that we just cannot afford to do so despite our best interests. A day spent in sick leave by an employee can cost us thousands of takas worth of export material.” In fact, most garment factory owners prefer to employ unmarried women for fear of pregnancy related problems, and many female workers lie about their marital status to get the job. Meanwhile, as of January 2011, public institutions are required to grant their female employees a six month long paid maternity leave. Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chowdhury, State Minister for Women and Children Affairs told The Daily Star that at least 1.21 crore female employees will be entitled to the leave so that they can exclusively breastfeed their newborns for six months. “This move will enormously help increase the productivity and motivation of the working women and achieve the millennium development goals by 2015, the target year,” said the minister. Although an admirable move, the amendment only applies to those who work permanently for the government and leaves out private and informal sector employees. “I only got three months off, and it would have been really helpful for me if I had an additional two months,” complains Hasna Reza, an administrator at a corporate media house. A large number of temporary government servants are also denied maternity leave and benefits in violation of the Bangladesh Service Trust, which stipulates that maternity leave can be granted to a temporary government servant provided that “she has been in government service for at least nine months immediately preceding the date of delivery.” Kohinoor Mahmood, project coordinator of Women Workers Development project of the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies, explains that it's more cost effective for government institutions to hire contract labour, to whom they don't have to give any benefits. “Temporary female workers are denied maternity rights, even if they have worked for a long period of time at a particular job. They are not given a contract, so there is no proof of how long they've worked. Even the government offices such as Titas, Public Works Department and city corporations do not provide benefits to their female staff,' says Kohinoor.

Institutions are supposed to provide more than just maternity leave to their employees. Section 94 of the Labour Act 2006 states that a workplace that has at least 40 women employees must have childcare facilities for the children aged up to six years, but only a handful of organisations in the country have provisions for day care centres. Even big corporations, media houses and many NGOs fall short of this requirement. “I wish we could have a day care centre in our office. That way, I could give my children some time as well as provide them a safe and secure environment,” opines Sheila Narmeen, an executive who has to work long hours. “Now I have a helping hand to look after them in my absence, but what about those women who don't have their families with them and cannot afford outside help? Where will they leave their children?” Women rights activists have tried to address some of these issues at the national level as well as within their own organisations through enacting gender-sensitive policies and programming. Labour unions are no longer as active as they once used to be, and in many crucial labour-intensive sectors there are no formal unions. Even within labour unions, the concerns of women aren't always addressed. The government has taken a few notable initiatives over the past few years, but it must ensure their implementation in different sectors of the economy so that all women workers benefit from them uniformly. Most immediately, the government must take some measures to provide protections to the more than 97 lakh women working in the informal sector who aren't covered by the Labour Act 2006 and remains a very vulnerable segment. Meanwhile, private institutions that purport to be progressive, should do more to ensure that they offer their women workers a more supportive and gender-friendly work environment. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |

||||||||