| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 10| March 09, 2012 | |

|

|

Profile Living Through the Lens A snap-shot of Sayeda Khanam, Bangladesh's first woman photojournalist Tamanna Khan Mid-twentieth century Pabna: Upon her aunt's insistence, a frightened little girl hesitantly stands in front of the one-eyed box covered in black cloth. The object looks like a square-headed monster on a tripod. Who would have imagined then that the little girl would one day capture the world with this very object? “I never thought that this camera will one day become my life partner,” chuckles Sayeda Khanam, Bangladesh's first woman photojournalist. Sitting in the sparsely decorated living room that still carries the aura of the past, the 75-year-old veteran photographer tells the story of the making of a photojournalist. She is the youngest amongst her four sisters and two brothers all of whom have established themselves in different fields of education, art and culture. Sayeda, however, could not attend school regularly because of chronic ill-health. Surprisingly, this gave her the time to appreciate the bounties of nature.

While lying in bed like Tagore's Amol, Sayeda would look out her bedroom window enthralled by the beauty of the trees, birds and mostly the Padma River. “As a child, the varying colours of nature left an impression on my mind. I used to wonder how I could retain these images,” she says. The answer soon came to her through a black square box. Sayeda's maternal aunt, Mahmuda Khatun Siddika, a poet, loved posing in front of the camera and getting her and her family's pictures taken. Being her aunt's little follower, Sayeda became acquainted with the camera at a very young age. Once while visiting Kolkata for treatment, she went to see an exhibition, “Life” by an American photographer. There she first came across the artistic aspect of photography. “There were lots of pictures of people-- photos of their life, their feelings -- laughter, sorrow and grief. While watching those I began to comprehend that a photograph is not only a picture, it is an art,” says the artiste in Sayeda. There she had a row with a friend, who rejected photography as a form of art. In response, Sayeda threw a challenge at her friend saying, “You just wait, one day I will show you that photographs too can be art.” Years later, Sayeda's photograph of a woman praying in the first light of dawn in the solitary premises of the Delhi's Jumma mosque received an international award. Sayeda's first camera was a small Kodak box-camera, gifted to her by Lutfunnessa Chowdhury, a close friend of Sayeda's elder sister, eminent academic Hamida Khanam. “I took my first picture in Kolkata. I was about 13 or 14 then. My first subjects were two Kabuliwalas, passing by the Victoria Memorial,” she fondly remembers. “Rabindranath's 'Kabuliwala' had made an impression on my mind. As a result, I wanted to take a picture of a Kabuliwala,” she explains.

Sayeda's obsession with photography grew with time, which compelled her sister Hamida to get her a Rolleicord camera from the US. “I still use Rollei. Although there are digital cameras now, I feel comfortable with a Rollei,” she says giggling like a teenager. Unlike photographers today, Sayeda did not receive any institutional training on photography. Looking back to the Dhaka of the 50s' Dhaka, Sayeda says, “There were only two studios in Dhaka, one called Das Studio and another Jaidi's Studio.” Sayeda often went to Jaidi's studio to get her photographs printed. Impressed by her photographs' composition, light and other aspects, Jaidi, the studio's owner, gave her foreign magazines on photography. “He told me to look at the pictures taken by prominent photographers and note the exposure and aperture given below. At that time, photographs could not be taken without (adjusting) aperture and exposure. We had to take light, time and distance into consideration while taking a picture. He told me to go through that to get an idea and also to read the articles,” says Sayeda reflecting on her first photography lessons. Jaidi also helped Sayeda participate in the international photography exhibition held in Dhaka in 1954. Later on, one of her pictures received an international award at Cologne, Germany. She also won the first prize in 1960 in the All Pakistan's Photo contest. Her career as a photojournalist began with Begum, the first magazine advocating the rights of Bengali Muslim women. Sayeda's aunt Siddika introduced her to Mohammad Nasiruddin, founder of the magazine. He immediately assigned her to take cover pictures for Begum and also cover events organised by women across the country. The opportunity opened the gate to a whole new world for Sayeda. Soon her pictures began to appear in the pages of Pakistan Observer, Morning News, Dainik Bangla, Dainik Purbadesh, Sangbad, Ittefaq, Pakistan Khobor and others. She even started to cover important events as a press photographer. One of those event was when Queen Elizabeth II visited Bangladesh, the then East Pakistan, for the first time. “I was the only (Bengali) woman in a simple blue sari with a camera in hand, amongst the hundred other fellow male journalists,” she informs with a grin.

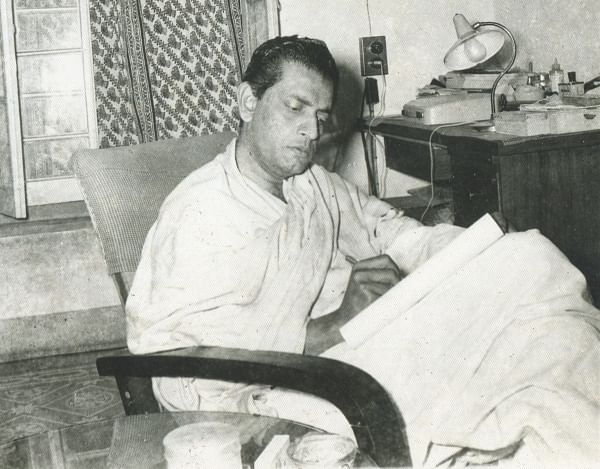

Her profession brought her close to many dignitaries. Some of them inspired her to move forward, braving all negative social barriers. One such person was the illustrated writer and film-maker Satyajit Ray. While working as the correspondent of the film magazine Chitrali in the 1960s, she showed interest in interviewing Ray. “But Parvez Saheb (Muhammad Parvez, the then editor of Chitrali) did not show any interest,” she reminisces. Not only her editor, everyone she knew in the cine-world, discouraged her, as Ray was known to be a very reserved person. Yet she went forward and called him, requesting an interview. He immediately agreed. Surprisingly, Sayeda not only got an exclusive interview from Ray but also became his family friend. Ray had encouraged her by remarking that very few women of the country chose the profession that Sayeda embarked upon. For thirty years, Sayeda had captured the life and work of this talented man through her lens. After Ray's death, Sayeda's photography exhibition on Ray, held in India and Bangladesh, received many accolades. When very few women of the country dared to even work outside the four-walls of homes, Sayeda had journeyed around the country in a simple sari with a camera on her shoulders. “Sometimes people used to throw stones at me, but I never shared these incidents at home,” says the woman, whose courage broke through all social norms. She even risked her life in pursuit of her passion. While attempting to take photographs of the defeated Pakistani Army on the eve of Bangladesh's freedom on December 16, 1971, she got into the line of fire. “We (she and her companions) hid ourselves behind a mango tree while the machine-gun bullets cut through the air right past our ears,” she relates, still shuddering at the memory, 41 years later. To Sayeda, photography has been a passion. She never worked for any remuneration. “I used to get conveyance expense and money to cover the cost of developing the film,” she says. Yet, she never lacked motivation for doing her job, which she continued while studying masters in Bengali and Library Science at Dhaka University. Even today, Sayeda often goes out on photographic expeditions, taking her life companion, the camera, with her. Photojournalists of Bangladesh look upon this brave and extra-ordinary woman for inspiration and courage.

|

||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |