| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 29| July 20, 2012 | |

|

|

Special Feature True Heroes The physically challenged in Bangladesh frequently come up against social barriers to their integration into the mainstream. It happens at educational institutions, workplaces, at service providing organisations under the public and private sectors and so on. The burden of creating a difference for the physically challenged has fallen on a bunch of young shoulders, who have themselves suffered the ignominy of being termed as 'disabled' or 'useless' by society. In this week's issue, the Star pays tribute to such heroes. Naimul Karim

It took Saiful Samin sixteen calculated steps to reach the conference room of his office. Despite repeated requests, he refused to be interviewed at his cubicle. “I don't want to disturb the others working around me,” he says with a smile. For a moment, it was quite difficult to believe that this was the same person who lost both his legs in 2008 after a train accident. He merely walked on his artificial legs, with crutches, happy to show me around his workplace. As we reached the room allotted to us, Samin politely asked one of his colleagues to pull a chair for him. Like a gymnast, he balanced himself on his crutches, trying to measure the exact distance between his back and the chair. After a whole minute of precise assumptions, Samin took his seat. “I'm ready now,” he says, once again with a warm smile. Today, Samin works as an online journalist for the Daily Prothom Alo. An accident that took place four years ago, while he was out reporting, changed his entire life. “ It was on June 20, 2008,” he says, and then followed a long pause, almost as if he was recalling the excruciating moments he had to go through ever since the accident. “My life has changed drastically.” A journalism graduate from Dhaka University, it was Samin's dream to be a reporter. “Till 22, I was always on the run, never slept in time. I used to wake up early in the morning, run to class and then go to work. After work I used to go to the addas at the university campus. I used to talk to friends till late at night,” he recalls.

As ironic as it may sound, it was a mishap at his dream job that lead to his current situation. “I was an assistant reporter when the accident took place. I obviously had to sacrifice a lot of things ever since then. My body can't function like before,” he says. Relocated in Mohammadpur, Samin prefers living without his family and leading an independent life. “I have a paid-helper who takes me to work and does some of the chores that I can't handle. My parents are currently employed in my home town. So it's not possible for them to come here. Considering the scenario, living alone is the ideal situation for me,” he says. While Samin may not have to face the travails of a daily reporter, he however, like any other online journalist, has to be accurate and work with extreme speed. “Journalists who work for the paper usually have a set deadline. In my case, I need to edit a story as fast as possible and upload it at that very moment. We have to bring the news out before our competitors. So, there's a lot of pressure,” explains the 25-year-old. Apart from his office work, Samin remains busy in his own writing endeavours. “I wake up at 7 am on working days and leave for office by 8. I have lunch at work and go home by five. By then I get a little tired and sleep for a bit. At night, I try writing theory based articles on journalism ,” says Samin, whose first book came out in August last year. Samin's newfound aim is to publish academic books on the principles of journalism and communication. “Journalism students in Bangladesh depend on either American or English books during their higher education. As a journalism student myself, I went through the same phase. That's the reason why I'm trying to write Bengali journalism books; so that upcoming generation can study based on a local journalist's perspective,” he says. The absence of his limbs, he claims, affected him in ways that he never could have imagined. “I didn't have artificial legs when I was giving my undergraduate exams, and I couldn't write properly. It was then that I realised that your legs provide a certain amount of force that enables you to write. Giving my exams, right after the accident was a horrible experience,” recalls Samin. Despite keeping himself motivated for the most part of the day, there are times, Samin claims, when he just can't help but wonder about how different life could have been had he decided against doing the train-story, four years ago.

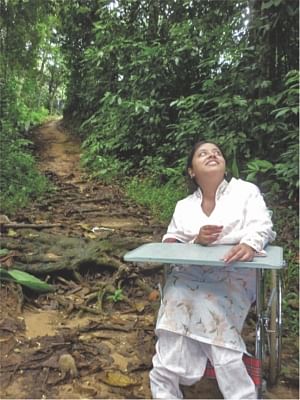

“It's kind of a battle between my brain and my body. My brain has grown with the idea that it can do a number of things, but my body doesn't support it. Another factor is that my body is in constant pain. Because I don't have legs, my blood circulates goes up to a point and then stops. That's quite painful and it always happens,” says Samin. He describes the battles between his brain and his body as a game that he plays every day. “I try to calm myself down, I tell myself that this is my life now and try to move on. There are times when different teachers tell their students about me and try to encourage them. Some of my friends, whenever they're depressed, come to me for help. All these things encourage me to do well, time and again.” Despite the relentless pain, Samin feels that he is in a better position than many others. “I'm lucky to be working here today. Otherwise there really is no hope for the physically challenged in this country. I don't think society cares. People won't tell them to die and neither will they be provided with the facilities that they require to survive!” he exclaims. Samin continues to work for Prothom Alo today and hopes that his struggle and the events in his life can encourage others to lead a better life. At the age of 10, Sabrina Sultana was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, a disease that made her muscles weak and affected the movement of her limbs. As she grew older the problem started to get worse. Sabrina was forced to leave school and spent most of her time inside the four walls of her room. Her life, as she describes it, was a 'dark cage'. “My family used to go visit many places, attend many programmmes. But I was always at home. People used to stare at me or mock me when I stepped outside my house. My parents were quite embarrassed. Numerous questions from all quarters used to snatch away my happiness,” says Sabrina Constantly harassed, Sabrina almost gave in to society's pressure before her family received another setback: the youngest member of the family, her sister, was also diagnosed with the same disease. “I saw the doors getting closed for her as well. I could visualise the agonising life that she was going to experience and this made me revolt,” she says. Frustrated with the treatment of the physically challenged in the country, Sabrina took an ambitious step by writing a letter regarding the problems to the Prime Minister. Although the letter never reached the government officials, she pursued another means to continue with her newly-found fervour: Facebook. By spreading the contents of her letter to as many people as possible, Sabrina created a network and got in touch with people suffering from various disabilities. Together with her friend, Salma Mahbub, who suffers from polio, they came up with a Facebook group called Bangladeshi Systems Change Advocacy Network (B-SCAN) on July 17, 2009. B-SCAN became a forum, for people suffering from disabilities, to share their problems and let people know about the atrocities that the less-fortunate in Bangladesh continue to face. “We started dreaming of campaigns for awareness. Our aim was to make people aware and thus help us get our rights,” says Sabrina. With an aim to promote positive perceptions and attitudes associated with the 'differently-abled' people, B-Scan organised many public campaigns. The most recent one was to include ramps in buses for people on wheelchairs. “The communication minister heard our plea and has agreed to put up ramps on the upcoming buses. As of now, we are helping them make designs for the ramps. We are trying to figure out if it will be better to put them on the footpaths or attach them on the busses. There are a few complications but that will be settled soon,” claims Sabrina. B-Scan is also working on putting up wheelchair ramps on buildings. “According to the building code of 2008, every building must have a ramp. It's obviously not followed and that's why we have been constantly contacting developers and members of RAJUK to follow the code,” says Sabrina. For someone who can't talk for more than 10 minutes without getting tired, the travails of running a full-fledged organisation, for the physically challenged, is hard to imagine. One hopes concerned officials notice the effort put up by Sabrina and B-Scan and perhaps support such heroic endeavours. It would seem almost next to impossible to describe the kind of work that Ahmed Javed Chowdhury has done. From setting up schools in the different slums of the capital to helping the children living there adapt to their surroundings, the 35-year-old lecturer has surpassed many a boundary. One would feel that it was both society's ignorance and the excessive sympathy for his cause that motivated him. “I have been suffering from polio ever since I was 10 months old. The region where we lived didn't have access to proper medication. To make matters worse I was wrongly treated by a doctor in my village, which badly affected my leg. I went for a proper treatment after that but it didn't make much of a difference,” says Chowdhury. As a result of the improper treatment, Chowdhury continues to suffer from a limp on his left leg. However, the limp couldn't stop his participative nature. “As a child, I used to sit out of cricket games, but then I organised a number of cricket tournaments. At the university level I was a founding member of the Sanskritik Sanghatan in East West University,” he says. A business graduate, Chowdhury worked in a number of telecom companies before settling down as a lecturer. He, however, faced his share of difficulties before getting the 'right' job. “It's difficult. Even though people talk to you normally, their body actions display something else. In my previous jobs many people thought that I wouldn't be able to work and many others took pity on me, which is something that I really can't tolerate,” claims Chowdhury. Narrating one such incident, he says, “One of the companies I worked for sent me to Mymensingh, where I had to live on the third floor. The area where I lived in was filled with Kaccha roads and was extremely muddy. It was a nightmare, honestly speaking. I asked the company to shift my post, but they refused, so I had to leave.” Apart from being a lecturer, Chowdhury works at the grassroots level, teaching children in the various slums of Dhaka. With organisations such as the 'Banglar Patshala Foundation' and 'Shakti Bidyalaya' Chowdhury has introduced a completely different stream of education; one that emphasises on 'learning to survive' and healthcare. “In 2008, my bua's child was killed in a road accident. The incident affected our family a lot since she had been working at our place for a long time. Following the accident I went to her house and tried to explain to the kids in the slum regarding the dangers in their area. It didn't seem like they were listening. Ever since then I regularly went their and started teaching the children. The slum-dwellers provided me with a small room and that's where the classes used to take place. That was where the idea of Shakti Bidyalaya stemmed from,” explains Chowdhury. Shakti Bidyalaya aims to provide children with the sense of the danger present on the roads. The mass education programme has integrated the basic needs for Knowledge of Survival with formal education. Currently there are six branches of this school. “Our education system has not developed in the right manner. The students in the slum need to be taught based on their surroundings and not based on just things written in books. This was the one of the ideas behind the organisation,” he explains. Ahmed Chowdhury believes in creating a different society in the future through his educational schemes; an informed society that can perhaps one day relate to the troubles of the physically challenged in Bangladesh; an aspect that has long been ignored in this country. As he puts it, “People like me don't want sympathy, but we do need some sort of a basic support. A government-building today might not even have railings at the steps; forget having a wheel chair ramp!”

|

||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |