| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 29| July 20, 2012 | |

|

|

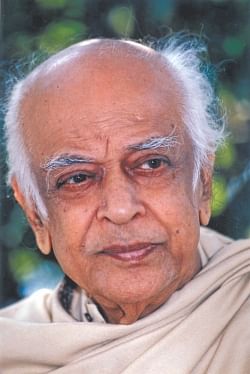

Musings Memories of Muzharul Islam Syed Badrul Ahsan

With Muzharul Islam's passing goes an era resting on principles and social commitment. With his death a generation of men and women believing in idealism and values gets to be depleted a little more. There was a stern quality about Muzharul Islam. The first time I met him was when, at his residence in Paribagh, his daughter Dalia Nausheen introduced me to him. Dalia and I were then students of English literature at Dhaka University and both of us happened to be involved with an English language teaching course at the Dhaka YMCA in the afternoon. That first meeting with the architect left me quite shaken, for though he responded to my 'salaam', it was quite obvious he was in little mood to spend much time inquiring after a callow young man. In those days of youth, Dalia made it a point to ask me over to her place, to tea and songs. She sang beautifully and I recall asking her, as a group of us sat on the lawn at Paribagh, to sing ekhoni uthibe chand aadho alo aadho chhaya te. The moon shone full in the spring sky and Dalia sang. There, among the group, was Nazia Jabeen, who I thought for a long number of years was her sister. It was only much later that I knew she was her cousin. Nazia was in school, hugely shy. Even so, Nazia served me some of the sweetest tea in the whole wide world. Thanks to Dalia and to the increasing frequency of my visits to Paribagh, I found myself opening up slowly before Muzharul Islam. I noticed that when I met him, he did not any more have the old hardness in his expression but actually smiled. He inquired about my studies. As time went on, he became a little freer and reflected, very briefly, on politics. Those were the times when Bangladesh lay in the grip of its first military dictator Ziaur Rahman. In those days, though I was quite aware of Islam's status as a significant architect in Bangladesh, I was rather ignorant about his place in the global architectural scheme. That he had been a student of Louis Kahn, that he had an important role to play in the emergence of what used to be, in pre-1971 times, the Second Capital area were facts I would come to know of later. You could say that my preoccupation with English literature had quite left me unable as well as unwilling to look into the substantive nature of other subjects of human study. As the years wore on, though, I went into a gradual learning process about Muzharul Islam and the symbolism he was in the architectural grandeur of Bangladesh's landscape.

But in those early 1980s, it was an avuncular Muzharul Islam that I chanced to meet in the quiet, almost pastoral ambiance of his home in Paribagh. That home does not exist any more. Neither does that huge lawn where, in somewhat of trepidation, I said hello for the first time to Professor Noorun Nahar Fyzennessa. Her daughter Sadya Afreen Mallick stood nearby. We did not speak because we did not know each other. That lawn now belongs in the past. It exists in the imagination and in that re-creation of a fleeting world come alive images of a hyper-active Muzharul Islam attending to a horde of good men and women gathered on his lawn on a day in May 1981. The occasion was a reception for Sheikh Hasina, newly elected president of the Awami League, just back home after six years in exile. I was, in a manner of speaking, part of it. And I was because of Dalia Nausheen. At the end of our YMCA classes, she told me about the reception. She wanted me to be there. And there we were. When Dalia told him I was there to see Hasina, Muzharul Islam flung a pretty hard look at me, then broke into a trace of a smile and said, “So you're gate-crashing, aren't you?” I gave him a sheepish smile and stood there, excited nevertheless by the prospect of meeting the new leader of the Awami League. She came, said hello to everyone and mingled with the crowd. Sheer excitement was in the air. The future was before us.

There is one other reason why that May afternoon at Muzharul Islam's residence rekindles memories. Francois Mitterrand had recently been elected president of France and Dr. Kamal Hossain was busy explaining the phenomenon of French socialism to another guest. Islam, happening to pass by, remarked that socialism was yet a mystery and not many could explain it. It was Islam's belief that socialism was the key to progress. Long after the demise of the Soviet Union and the decline of the Left, Muzharul Islam remained a staunch socialist in his conception of politics. On a fast-descending monsoon evening about a year later, I turned up at Paribagh yet once more, to find Muzharul Islam seated in his drawing room. When he saw me, he swiftly fetched a book from a nearby table and cheerfully informed me that it was one important book he was reading, one that I ought not to miss. 'May I borrow it?” I asked him. 'No, you can't”, he said. At that point, I was ready to do anything for Islam — make him a cup of tea, discuss the world with him, stand in the corner in undeserved punishment — in order to have him relent and give me the book to read. And he did relent, on one condition: I had to finish reading it that very night and return it to him early the next morning. I skipped and danced my way home in Wari, book in hand. As dawn broke, I finished reading the final page of the work, feeling happy at my achievement. Sometime after breakfast, I took a rickshaw ride to Paribagh and cheerfully returned the book to Muzharul Islam. He gave me a broad smile, the biggest ever that I was to get from him. That book was Lawrence Lifschultz's Bangladesh: The Unfinished Revolution. The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

|

||||||||

|