Profile

The Mysterious World of Oriental Art

Fayza Haq

|

Dr Abdus Sattar

Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

With silvery curls and glasses, Dr Abdus Sattar, sits in his bungalow a haven near the TSC shaded by voluptuous mango and jackfruit frees. His shelves are full of leather bound books and topped by coveted prizes. The artist, an amiable, modest man, is full of chuckles and anecdotes.

Yet despite the humility people in his circles know him for his expertise in Oriental art. Trained in the US as a Fulbright scholar and later in India, he, as the solitary student, and Hashem Khan as the Head, had established the Oriental Section at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Dhaka University.

So how does one relate to Oriental Art? Is it an escape from reality – a place to take shelter from the destructions and devastations around one? Dr Sattar says: “Oriental countries, as we know them – Pakistan, Nepal, Japan and Korea have such a trend of art that is of Asia alone. We, in Asia, wish to arrest the sweeping influence of the west. We want to make it go side by side the modernity of the US and Europe. Think of the famous artists of Bengal– Abanindranath Thakur and Nanda Lal. When Pakistan got divided, the world-famous painter Abdur Rahman Chughtai, left us and went to the west. The well-known artists of the Bengal School were totally different from him. Chughtai took from Moghul, Persian and Turkish Art. He set up a style of his own. Meanwhile, we, who are working in Bangladesh, learn and absorb Oriental Art of the past and try to set up a school of our own–so that sensibilities of Bangladesh can be recognised and preserved. This is not to say that we've moved away from modern existence and the reality around us".

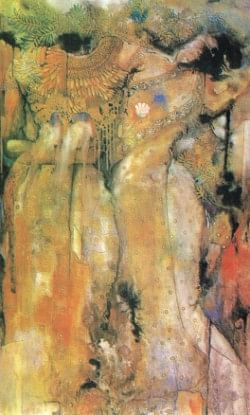

Man, birds and animals, the flowers and trees are part of the actuality around us. However, our manner of delineation is different from that of the west, he says. There are variations, with inclusions of abstractions – variations and offshoots, as seen in some of the works of say, Nasreen Begum. "Yet artists, like Nasreen," says Dr Sattar, "have tried to preserve the beauty of Oriental Art. People seeing our form of Oriental Art recognise how different Bangladeshi Oriental Art is. It is different from that of say Oriental Art of Japan, China or Iran."

Fallen Tree

"We learn about them. We try to absorb them. But ours remain that of our own – something separate, with an identity of our own.” We, for instance, says Dr Sattar celebrate 'Pahela Baishakh'. The 'hilsa' and rice must be maintained as our typical food. Similarly, there is the 'pitha' of which we are so proud. Our legacy and rich roots should surely not be lost with the progress of civilisation." Similarly, he adds, the pageants for Muharram and Eid, the delineations of which are kept in the National Museum, are memorable. Our calligraphy too must contain Bangla alphabets says Dr Sattar.

The Oriental Art Section was established to promote old, traditional art. This section was revived around 1978 and Sattar studied here after the pre-degree. The teachers in the Pre-Degree Section were Hashem Khan and Rafiqun Nabi. "The students in other departments were impressed by my work at the year end exhibition." says the artist.

Sattar next joined as a teacher himself. Others joined too, like Nasreen Begum and Showkatuzzaman, who are famous now for their own contribution to Oriental Art. Some, such as Kamrunnehar, have joined commercial art offices, as this was essential for their existence. Some have become art teachers in schools and colleges, says Dr Sattar. When exhibitions are held and workshops are arranged, at the Art College or Bengal Gallery or wherever, these artists join in, no matter what their current preoccupation may be.

|

A Bird |

Composition 1 |

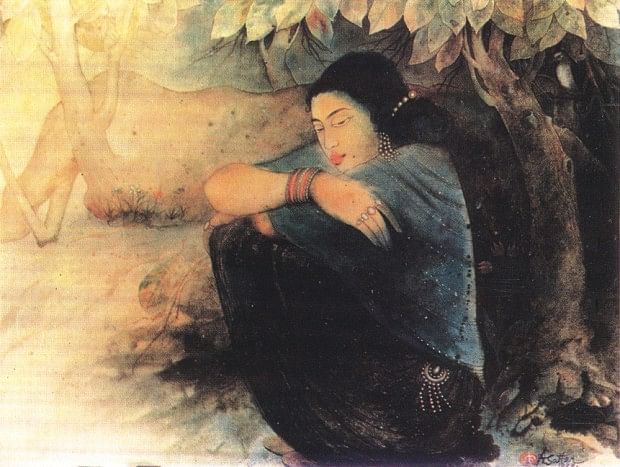

Has Dr Sattar always used the symbols of happiness like beautiful women, flowers, moonlit nights? Are the elements of suffering and pain not brought into his work? "The element of beauty is that when the viewer sees the art work he should get pleasure from it", says Dr Sattar. "Therefore", he says, "we artists contemplate deeply before we paint. The painter may show rivulets, cloud laden sky, a tree proud with snow white flowers, a delectable woman or a resting deer in a forest."

However even an optimist like Sattar has been affected by tragedy in terms of his work. During the 1971 Liberation War the Pak soldiers killed his friend and fellow-artist Shahnawaz. In the F Rahman Hall, there is a section 'Shahnawaz Chatrabash'. "There was no precise reason for killing him" relates Sattar, "the shooting had been random on March 25th night. Whomever the Pak soldiers got, they killed. It was this friend of mine who was the brain behind the cartoons, posters and masks that were brought out in the processions against the inhuman invaders." The Pak army had targeted this hostel in particular, he adds. Abdul Jabbar, another fellow student, had persuaded Shahnawaz to leave in time. However, the other had insisted that he would remain, and add the experience of the invading army to his writings for others to hear– when they came after him.

“When I went to examine the scene, later on, I found the wall and ground covered with bullets and blood. I have often used the images of the bullet holes in my works later on. In fact, I did a long series on the subject. I still include this subject in my work, from time to time. I have repeatedly delineated the men and women, who took part in the Liberation War. Rape, soldiers and mutilated bodies of the genocide are just as part of my experiences as any other Bengali of that time. The brutality and atrocities of the cruel Pak forces and their mindless destructions and inhumanities moved me just as much as others in our homeland. The pain and suffering in my heart and mind had to be expressed in my work in Santiketan, where I went to study on a scholarship.” says Dr Sattar who was in India from 1973 to 1975, as a student.

|

Couple 1, mixed media, 1983.

Photo: courtesy |

In India, he had the brilliant printmaker Somnath Hore. At present, incidentally, Dr Sattar is writing a book based on this icon of fine arts. Some of the pictures based on the women – who had been brutally treated – included ones about to drink poison from cups, not seeing any future for them in society. These had been litho prints, and are kept in the Rajshahi Museum. The others have been sold. A few works of this nature are still there, says Dr Sattar. During the annual three day festival, Nandan Mela, based on Nandan Bose held at Biswabharati Biswabidaleya, Santiniketan, Sattar's albums containing such works still sells.

What was his reason for going into Oriental Art–what was its appeal for him at that time? It was obviously a big risk, says Dr Sattar as it was not quite established before his time. But he felt that Oriental Art should have been recognised in Bangladesh as another branch of visual art which should have been nurtured. The artist, as a young man, had read enough books in the library to be drawn to it. He was about 18 or 19 at that time, though taking a big risk. Maybe, if this particular artist had not ventured, this

branch of art may not have become popular.

What was his education background like? Did he face any opposition when he decided to study fine arts, or did he get inspiration from his childhood surroundings, as many artists have done? "I studied at a village in Natore, Rajshahi; and didn't even know that there was a certain place in Dhaka where such inclinations, as regards to fine arts were encouraged. No one in my family had any idea about such studies. I, on my own, read books and got inspiration from them. Seeing my drawing, my school headmaster, gave me the cue. My father, at home, seeing my drawings, would take delight in my efforts, and was proud of them. I was about 16 at that time.”

Cubists, Surrealists, Dadaists and such modern artists took great pains to delineate objects of discomfort, agony and pain. Art, as one saw, often, in one's early days was peace, beauty, tranquillity and harmony. Has modern existence nothing to offer man as portrayal of life around him, except images of death and destruction? In which direction is art moving – in Bangladesh, for instance? To this Dr Sattar says, painting is not like book illustration. Picasso, in “Guernica”, did not wish to work to promote or illustrate war. But art does reflect social and political life around the artist. “What I myself saw in 1971, I brought into my own work. Bullet holes are still found as in Ahmed Nazir's popular work which were recently seen at Bengal Gallery. Shahabuddin's paintings also carry the Liberation War theme and are seen as the fastest selling paintings in Chitrak. During World War II Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin made the famous black and white Famine sketches– which stirred the world, and awakened the minds of men. Artists, however, blend the images in colours in a manner that the work stirs the onlooker, but the works remain art pieces, not mere illustration.”

|

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |