Law Campaign

The quest for a right to information law

Md. Rizwanul Islam

|

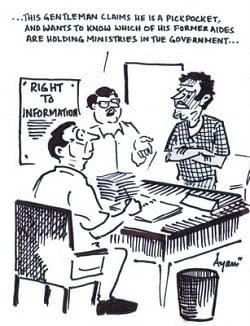

Right to information.cartoon |

We cannot make real choices in any area of our lives unless we are well informed. This is applicable in politics, the workplace, education, civic life and so on. Information influences our choices and decisions. Unless we have proper, accurate information, we cannot fully exercise our rights and freedoms. Secrecy in public sphere is conducive for the dominant class in a state, generally the government and bureaucrats- civil or military. If citizens can be kept in the dark, it becomes easy to rule for an autocratic, corrupt administration and vice versa. Jeremy Bentham noted centuries ago, “The eye of the public makes the statesman virtuous. The multitude of the audience multiplies for disintegrity the chances of detection.” (Quoted in Blacked Out by Alasdair Roberts) The Supreme Court of India, in S.P. Gupta and Others v. President of India and others [1982] AIR (SC) 149 noted that, “Where a society has chosen to accept democracy as its creedal faith, it is elementary that its citizens ought to know what their government is doing... It is only if people know how government is functioning that they can fulfill the role which democracy assigns to them and makes democracy a really effective participatory democracy.”

In 1946, one of the very first resolutions of the UN General Assembly stated, “Freedom of information is a fundamental human right and ... the touchstone of all freedoms to which the United Nations is consecrated”. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 also contain similar expressions. Although these provisions recognize the right to seek information, they do not impose a corresponding duty to any entity. Hence, in 1997 the UN Commission on Human Rights issued a request to the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression to look more closely into the right to seek and receive information. The following year, the Special Rapporteur reported on the issue noting that “The right to seek, receive and impart information imposes a positive obligation on States to ensure access to information, particularly with regard to information held by Governments in all types of storage and retrieval systems”.

The first law granting a right to access government information was passed in Sweden as early as in 1776. Interestingly, Sweden remained the only country with such legislation for more than a century until Finland enacted a similar law in 1951. In the last few decades almost all economically advanced countries have enacted right to information laws and increasingly developing and less developed countries are following suit. It is important to note that these laws vary a great deal, for instance, in Sweden citizens can have access to their fellow citizens' income tax return which would in most other jurisdictions be considered as a confidential document. On the other hand, there are countries like China where freedom of information law grant little access to information than granting a 'symbolic right'.

How can right to information law have an impact? A concrete example may give us some directions. In 1999 the Bolivian government leased control of the water supply in the city of Cochabamba to a private company. This assignment probably had something to do with the fact that the World Bank had told the mayor of Cochabamba that a US$14 million loan to upgrade the city's water supply was qualified on privatisation. World Bank had placed the same condition on a payment to the government of an amount of US$600 million in international debt relief. The contract was awarded through a secret tender where there was just one bidder- a company called Aguas del Tunari. No one knew who they were or where they had come from, but they were allowed to have control of the city water supply until 2039. Within weeks of Aguas del Tunari's taking over of water supply, it increased water supply charges by 200% or more. For local workers, living on wages of about $60 a month, this meant paying up to a quarter of their income just for paying water usage bill. Local people quite naturally resisted the privatisation deal. After a popular struggle over several months they won. First the rate rises were reversed and then Aguas del Tunari was kicked out. In the course of the struggle to get their water back, the people of Cochabamba unfolded some startling facts. Under the terms of the privatisation deal, the company was receiving a guaranteed annual profit of 16% but the company had made almost no up-front investment in the city's water. If the people had access to these pieces of information, it is inconceivable that the local government could enter into the deal in the first place. It is not improbable that this Bolivian incident would have a number of parallels, at least to some degree, in our country.

It is not just in less developed countries, with lack of a democratic culture, where government and local authorities might be facing embarrassing revelations by people's exercise of right to information. Such laws can and do embarrass even the governments in advanced democracies. For example, a confidential memorandum containing the response of a British army chief to a query from British ambassador in Venezuela regarding whether the British government was ready to endure bribery of foreign officials by British arms dealers had the following sensational revelation:

“I am completely mystified by just what your problem is... People who deal with the arms trade, even if they are sitting in a government office...day by day carry out transactions knowing that at some point bribery is involved. Obviously I and my colleagues in this office do not ourselves engage in it, but we believe that various people who are somewhere along the train of our transactions do. They do not tell us what they are doing and we do not inquire. We are interested in the end result. “ (Quoted in Blacked out by Alasdair Roberts, page 7)

It is generally agreed upon that everyone should have access to information held by public bodies. The basis of such a perception is that public bodies hold information not for themselves but as custodians of the public good. Hence, they should provide us with those pieces of information that they hold because it is our information entrusted in their hands, not their information. However, as many functions of public bodies are now being performed by private bodies, the information held by the latter can equally be important for citizens. People should also have the right to access to those pieces of information held by private bodies that is necessary for the exercise or protection of any other right.

A critical point for an effective right to information law is the formulation of proper exceptions that is keeping certain kinds of information away from the scope of the accessible information for securing a few legitimate objectives. The problem is that the object of the law itself can be defeated by an expansive scope of exceptions framed in the name of ensuring national security, law enforcement, foreign relations and so on. All these matters should be clearly defined and should not be too wide to unduly defeat the object of the law. In cases where an application is rejected on any of these exceptional grounds, it should ultimately be upon the court of law to decide whether the law has been applied properly or not. Otherwise, there can be a mockery in the name of granting the right. It should be mentioned that we have the Official Secrets Act, 1923 in force in Bangladesh, which is a formidable barrier to access to information. Although, the Act could serve to achieve legitimate purpose such as prevention of spying, maintaining the security of the state etc, the use of vague or ambiguous wordings in the Act has made it very much open to abuse.

No right of information law can be meaningful unless a culture of seeking information can be nurtured in a society. An effective right to information law needs citizens who are willing to exercise their rights. The human rights NGOs should strive for educating the public about the importance of this right. Assuming that a law is passed creating a right to information, they should campaign for educating the public on how to exercise the right.

It is often contended by some that a right to information law in a country like ours with high rate of illiteracy would have no impact. Despite some merit in the contention, it is an essentially flawed argument. A right to information law at its best would foster a culture of accountability of the different stakeholders and at its worst would have no impact at all. Even this worst possible outcome in this case would have no adverse implication. Furthermore, even if citizens at large do not resort to right to information law in near future, a proper right to information law could hopefully be utilized by our vigilant media and strengthen the trend of investigative journalism. Concern is also expressed that a right to information law can be an administrative burden and too much thrust for government information can make administration less efficient. However, this can be remedied to a great extent by charging reasonable fees for access to information. The fee thus levied can be utilized for investing in setting up adequate mechanism for dealing with application for access to information.

The present interim government has strongly advocated for eradication of corruption in all spheres of public life. It would be fitting for this government to enact a meaningful right to information law that would empower citizens. By enacting a truly significant right to information law, this government can herald a new beginning in the fight against corruption.

The writer is PhD Scholar, Department of Law, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.