Women's

Day Special

Human

Rights analysis

Shattered

Reflections: Acid Violence and the Law in Bangladesh

Saira

Rahman Khan

I

never wanted to look into a mirror again"…..

"Why do people think it is my fault?"…..

"The pain was unbearable and I wanted to die"

….. "I am afraid to go home because the person

who did this to me is still roaming free."….

" I am only 15 and I want to go back to school"…

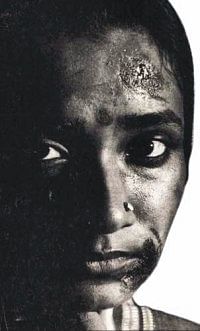

such are the words of girls and young women who have been

victimised with acid. Needless to say, the flinging of

acid on the face and body of a person in truly a heinous

act vengeful and calculated. It leaves both physical and

mental scars, which usually stay for life. The victim

will always be in pain. The old saying goes 'hell hath

no fury like a woman scorned'. However, when it comes

to acid violence, things are a little different. A large

majority of the women who have fallen victim to this are

those who have rejected marriage proposals and proposals

for sexual relationships, the perpetrators being the scorned

suitors. To date, the perpetrators of acid violence have

always been men.

What

makes a man so vindictive that he must throw acid on a

person in order to seek revenge? Are there any socio-cultural

factors that affect the male members of society to such

an extreme that acid violence is the only way in which

to resolve a dispute? Why is it that in a group of friends,

only one will think about throwing acid? There are, unfortunately,

no concrete evidence as to what compels a person to throw

acid. However, if we look at the tool used, we see that

it is comparatively cheaper that a knife or a gun, it

can be thrown from a distance - avoiding proximity and

giving the perpetrator time to flee the scene - and the

result is painfully permanent. The perpetrators are mainly

unemployed, frustrated youth, and, due to a lack of recreational

facilities in rural Bangladesh, whose idle minds sometimes

became the 'devil's workshop'. If such a youth was rejected

by a young woman, that might be construed as an insult

to his masculinity and that is when acid may seem to be

the most effective means to make the girl remember her

'mistake'. The concept of women as chattel or objects

is, sadly still regarded in the patriarchal society of

Bangladesh. The fact that the perpetrator has the time

to buy the acid and lay a plan on how to administer it,

shows the cold-blooded nature of the crime.

What

makes a man so vindictive that he must throw acid on a

person in order to seek revenge? Are there any socio-cultural

factors that affect the male members of society to such

an extreme that acid violence is the only way in which

to resolve a dispute? Why is it that in a group of friends,

only one will think about throwing acid? There are, unfortunately,

no concrete evidence as to what compels a person to throw

acid. However, if we look at the tool used, we see that

it is comparatively cheaper that a knife or a gun, it

can be thrown from a distance - avoiding proximity and

giving the perpetrator time to flee the scene - and the

result is painfully permanent. The perpetrators are mainly

unemployed, frustrated youth, and, due to a lack of recreational

facilities in rural Bangladesh, whose idle minds sometimes

became the 'devil's workshop'. If such a youth was rejected

by a young woman, that might be construed as an insult

to his masculinity and that is when acid may seem to be

the most effective means to make the girl remember her

'mistake'. The concept of women as chattel or objects

is, sadly still regarded in the patriarchal society of

Bangladesh. The fact that the perpetrator has the time

to buy the acid and lay a plan on how to administer it,

shows the cold-blooded nature of the crime.

What

happens when a person is attacked with acid? Unless treated

with water immediately after the attack, acid corrodes

the skin, burning its way down to the bone. In some instances,

the bone also melts away. Needless to say, the pain is

excruciating. Treatment is also painful, as the burnt

upper layers have to be gently peeled away to allow for

healthy scar tissue to form. There is always the fear

of infection and victims who have large areas of their

bodies burnt are rendered immobile. What of the availability

of acid? Unfortunately, acid it sold openly in chemist

and homeopathy shops and local medicine dispensaries and

can be found in goldsmith workshops and shops selling

and repairing car batteries. It is also openly sold around

the tannery factories. Despite the law, there are no checks

as to the trade in acid and other corrosive substances

and those selling the liquid ask no questions. There is

even, allegedly, a good trade in cross-border smuggling

in acid, which may play a role in contributing to the

high rate of acid violence in the border districts.

The

laws

The President of the Peoples' Republic of Bangladesh approved

the Acid Control Act 2002 and the Acid Crime Control Act

2002 on 17 March 2002. The laws were promulgated to meet

the demands that acid crimes be controlled and perpetrators

receive swift punishment and that the trade in acid and

other corrosive substances be guarded by legal checks

and balances to prevent their easy accessibility.

A

lot of though has been given to the drafting of these

laws, especially in the area of compensation to the victim,

carelessness of the investigation officer, bailability,

magistrate's power to interview at any location, medical

examinations and protective custody, the setting up of

an Acid Crime Control Council and (District) Acid Crime

Control Committees, establishing rehabilitation centres,

licences for trade in acid, etc.

According

to the Acid Crime Control Act, this law aims to rigorously

control acid crimes. It houses stringent punishments ranging

from the death sentence to life imprisonment, to between

fifteen to three years and a hefty fine. The variations

of punishments depend on the gravity of the crime. For

example, if the victim dies due to the crime, or totally

or partially looses sight or hearing or both or 'suffers

disfigurement or deformation of face, chest or reproductive

organs', the punishment is the death penalty or life imprisonment.

Interestingly enough, the Act provides that if the Acid

Crime Control Tribunal feels that the investigating officer

has lapsed in his duty in order to 'save someone from

the liability of the crime and did not collect or examine

usable evidence' or avoided an important witness, etc.,

the former can report to the superior of the investigating

officer of the latter's negligence and may also take legal

action against him.

The

Acid Control Act has been introduced to control the "import,

production, transportation, hoarding, sale and use of

acid and to provide treatment for acid victims, rehabilitate

them and provide legal assistance". The National

Acid Control Council has been set up under this act, with

the Minister for Home Affairs as its Chairperson. Under

this Council, District-wise Committees have been formed

albeit, only in six or seven Districts to date. Members

of the Council include the Minister for Women and Children

Affairs, Secretaries from the Ministries of Commerce,

Industry, Home Affairs, Health, Women and Children Affairs,

and representatives from civil society as specifically

mentioned in the law. This allows for a broad spectrum

of representation. More importantly, according to this

law, businesses dealing with acid need a license to do

so, and the government has arranged for a Fund to provide

treatment to victims of the violence and to rehabilitate

them, as well as to create public awareness about the

bad effects of the misuse of acid.

The

realities

Despite the Acid Laws of 2002, why do annual figures on

reported incidents of acid violence continue to stay above

300 (where almost 85% of the victims are women)? Why is

it still so easy to procure acid and sell it openly without

a license? According to studies carried out by the Acid

Survivors Foundation, there are several reasons for this

and for why the law is not being implemented properly.

Some of the more noteworthy reasons are as follows:

There

is yet to be a separate, modernised Investigation Department

with trained investigators in the police force and overburdened

police are unable to carry out their investigation duties

properly. This may result in hurriedly written reports

and inefficient investigation. Many NGOs have called for

the formation of a separate department, but pleas fall

on seemingly deaf ears. Furthermore, there is not follow-up

done as to whether businesses are procuring licenses for

the sale and trade of acid.

Doctors

are unable to identify acid burns, due to lack of training

and medical certificates are not clear and sometimes vital

information is not noted down, thus weakening the evidence.

Furthermore, many doctors are reluctant to come to court

to give evidence. Lack of sufficient judges and judicial

officers in the lower courts causes delay in hearings

and cases are either not heard on time or remain pending.

Many

of the above findings are applicable to other sectors

where lack of implementation of the law causes serious

damages in matters pertaining to violence against women

such as rape and dowry-related violence. This being the

case, why are no steps being taken to rectify the matter?

Issues of violence against women still remain in the medieval

era in the country. Non-government organisations are doing

their bit to create awareness against acid violence and

the social and legal repercussions it has. The government

is now legally bound to do its share, under the 2002 Acid

Laws. A lot of power has been given to the National Acid

Control Council and it must gear up its activities and

not wait for NGOs to prompt it into action.

The

writer is an Assistant Professor, School of Law, BRAC

University.