The Story of Storytellers

By Risana Malik

The art of storytelling is timeless and universal, and for good reason. While books and movies are all very delightful, there's something about being told a story; to hear the changing modulations in a voice from a roar to a whisper, to watch the eyebrows on a face raise and drop, to feel a myriad different imaginations at work that develops an intimacy between tale, teller and audience, which cannot be found in other media. This art has served numerous purposes over the course of human history. They were, for the longest time, the only medium by which a family or a society's history could be passed down. And who can forget the eternally popular bedtime ritual that has never failed to frighten and fascinate children everywhere?

The art of storytelling is timeless and universal, and for good reason. While books and movies are all very delightful, there's something about being told a story; to hear the changing modulations in a voice from a roar to a whisper, to watch the eyebrows on a face raise and drop, to feel a myriad different imaginations at work that develops an intimacy between tale, teller and audience, which cannot be found in other media. This art has served numerous purposes over the course of human history. They were, for the longest time, the only medium by which a family or a society's history could be passed down. And who can forget the eternally popular bedtime ritual that has never failed to frighten and fascinate children everywhere?

The earliest stories, if 35000-year-old cave paintings are anything to go by, must have been simple and fundamentally the same, be they Old Stone Age people living it the Pyrenees or Aborigines in the Gibson Desert: they were anecdotes to relate hunting experiences or strange happenings, expressed using gestures and the local language, with images to aid the imagination. Which, if you think about it, isn't very different from how many stories are told even now. However, the art form has diverged magnificently over centuries and cultures, adopting a variety of new forms of expression and changing themes; some evolving rapidly before all but dying out, some struggling to survive modernisation, others still, flourishing well away from it all.

Europe: the Bards

It's ironic that Europe, where the first evidence of Stone Age storytellers was discovered, and whose legends and folklore are probably the best known, should have the fewest traces of its storytelling heritage remaining.

The ancient Greeks were great ones for stories before they tired of memorising epics and started writing plays. We had Homer, from around the 8th century BC and Aesop from the 3rd. The former with his legendary epics, the latter with his fables, they were, if you like, the forerunners of the narrative stories that developed in Europe.

To the North, the Vikings, with similar stories of their own wars and gods and other worlds, preserved their oral literature differently. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, they had no designated scholars and storytellers; it was usual for most Vikings to learn to recite poetry and remember the mythology that constituted their Eddas and Sagas.

Minstrels and bards began to flourish in Western Europe around the Middle Ages. The Troubadours of France and German Minnesingers were the poet musicians you'd find entertaining lords and nobles in their halls. They ranged from the wandering minstrels of the peasantry to professional musicians with patronage. The British and Welsh bards and seanchaithe of Ireland however, still preferred folklore and legends; years of training had them committing hundreds of lines of poetry to memory, not unlike the Homeridae. However, these poet-musicians soon had to relinquish their art to writers; and these once popular storytellers receded into the background of local traditions.

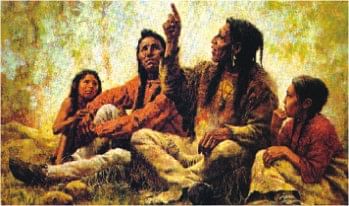

Native Americans: The Myth Keepers

The numerous Native American tribes shared a diversity of folklore and old traditions regarding it. While most members of the tribes were familiar with the stories, they were largely the forte of an elder of the tribe, the medicine man or the lore-keeper. The tales told were historical, explaining certain traditions of individual tribes, or fables about their animal spirits and totems; and, in certain tribes, these stories could be passed on only at the will of the myth keeper.

The Cherokee, for instance, would perform a scratching ceremony on those chosen by the medicine man. Only those marked by him with a rattlesnake-tooth could stay in his hut and hear the stories until dawn. The tales incorporated music and dance and, sometimes elaborate paintings.

The colonisation of America drastically reduced the population of these tribes and their cultural  significance was largely ignored, their stories only preserved by a few. It is has only been in the last century that Native American literary heritage gained some appreciation and a following, encouraging reunions and pow-wows where these stories could, to some small extent, be revived.

significance was largely ignored, their stories only preserved by a few. It is has only been in the last century that Native American literary heritage gained some appreciation and a following, encouraging reunions and pow-wows where these stories could, to some small extent, be revived.

Africa: the Griots

As with Native Americans, the storytelling culture of Africa is, for the most part, varied and rich in natural imagery and expression. Their stories are legacies of millennia and, even now, they are an integral part of everyday life as well as a significant building block in their religion.

By the Mande of West Africa, for example, the art of speaking itself is believed to be tied to the world of spirits. Hence, storytelling is left to a select few to master the complexities of the verbal and musical expressions, and to nurture the acute memory skills required. The power of the spoken word is said to invoke the Nyama, the higher powers of creation and destruction. The masters of these stories are called the nyamakalaw, or Handlers of Nyama, because of their ability to channel the energy. A similar concept of an ambivalent power is Ache, practiced by the Yoruba of Nigeria.

The Oriental artists

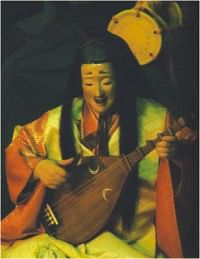

Around the 13th century, biwa-hoshi, or blind bards narrated epics about samurai battles. While these have drifted out of Japanese culture, the custom of Kodan still remains, which tells tales of heroic exploits; and uses props like paper fans, wooden clappers and a small platform called a shakudai.

A similar but more interactive kind was Rakugo a type of comic storytelling still practiced today and, as with many Japanese traditions, retains its rigidly ritualised form. The stories are intricate comedies involving dialogue between characters, and thousands of them can be traced back centuries, many to as early as the 13th century, when Rakugo began to evolve as an entertainment for feudal rulers.

Street storytellers can be still found scattered around East Asia. The custom developed some 3 centuries ago, as a picture-storytelling method called Kashimibai, using large printed cards as illustrations. In China, wandering storytellers used wooden clappers to signal their arrival and the beginning of a story. Picture cards were used in their lectures and parables too.

centuries ago, as a picture-storytelling method called Kashimibai, using large printed cards as illustrations. In China, wandering storytellers used wooden clappers to signal their arrival and the beginning of a story. Picture cards were used in their lectures and parables too.

South Asia: The Story Singers

From reciting epics 15 times as long as the Iliad for days on end, to puppet shows demonstrating said epics, India's storytelling practices are some of the world's most ancient, as well as elaborate, and still endure in numerous forms.

Similar to the kashimibai method of East Asia, the epic-singers, or Bhopas, of Rajasthan use paintings to enhance their storytelling. These performances, however, were grand affairs for whichever village they travel to, for the skills of the epic singers are passed on from father to son and the poetry of the bhopas is considered sacred. Indeed, the bhopa is believed to possess shamanic qualities and people attend these storytellings to be healed and blessed. The tales told are centuries old, legends of heroes and wars and martyrs and the spirit of each story's character is thought to possess the bhopa during the performance.

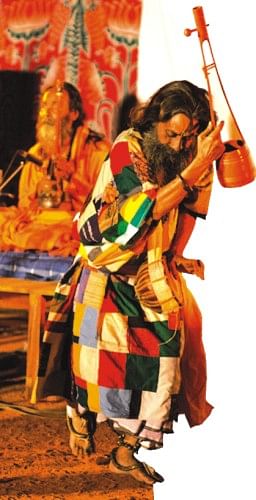

Closer to home are bauls, the wandering minstrels of Bengal. “Bauls”, derived from the Sanskrit word for 'mad' are often termed 'Holy Fools'. Their songs, descriptive and abstract, speak of the love between God and the human soul, and reflect their ultimate desire for the mystic union of the two.

So the next time you attend a family gathering and watch random people enthusiastically gesticulating as they relate some anecdote to anyone who will listen; or simply sit down with the grandmother for a few moments to hear how a remote ancestor rode a tiger to his wedding, think of Aesop, of the Ramayana, of the unnamed cave artists, bards and minstrels who told their tales over and over so that the world wouldn't forget. Think of how, through the tumultuous progression of the world, one of our most ancient traditions has held true.

It's a point worth remembering.