By Sabhanaz Rashid Diya

Photo: Sabhanaz Rashid Diya

I have rarely been to Old Dhaka. My first memories were that of an 11 year old who went there to attend a festival of a Hindu family and all I remember was that they served mouth watering delicacies. However, my recent visit to the same place left me enthralled. Our destination was Shakhari Bazar at the heart of Old Dhaka, a 600 feet long narrow street with overshadowing, brick constructions lining its sides. Its unique urban fabrication and centralization of the Hindu community made it a prime location for major Hindu festivals. The traditional businesses along the street with the homes of the owners on the upper floors were a situation unheard of in the fast-growing metropolitan Dhaka. Yet, it existed and was the norm of the Old Dhaka community. And perhaps, of all the things we tasted, saw and experienced, it was that exact custom of family bonding and geniality that attracted us the  most.

most.

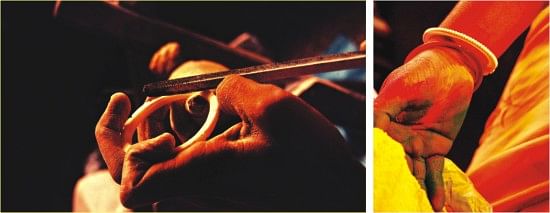

Shakhari Bazar is the ménage of 150 to 200 years of business in the craftsmanship of conch bangles. The Shakhari community borrowed its name from shakha (or, richly decorated conch bangles) made from shankho or conch shells. It symbolizes that a Hindu woman is married, and was also used by Vidya Shakha as a trumpet for mangal dhoni (sign of good omen). Almost every use of shakha carries a form of religious connotation.

Our curiousity behind the making and maintenance of such a tradition led us through the narrow alleys into the conversations of the locals about their heritage and history.

Prior to the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the Shakharis used to get the raw  material for their craft, the shankho (conch shell) directly from Calcutta through their agents. The shells were imported from South India and Sri Lanka. After 1947, import from Calcutta stopped altogether and the shells were directly imported from Sri Lanka.

material for their craft, the shankho (conch shell) directly from Calcutta through their agents. The shells were imported from South India and Sri Lanka. After 1947, import from Calcutta stopped altogether and the shells were directly imported from Sri Lanka.

The mass exodus of the Hindu community to India as the result of riots following the partition in 1947 left Shakhari Bazar deserted. It was only through pacts at national levels that things started simmering down when repatriation took place. This was followed by some effort by the government to bring back likeness of order in the area. Apparently, by 1953, at the behest of the government, reorganisation took place in the trade. Two organizations, The Conch Shell Industries and The Conch Shell Cooperatives started operating. The two companies between themselves shared almost all the members of the Shakhari community. As every single member of the community was a shareholder in either of the two companies, some sort of ownership over the craft was established.

Today, Shakhari Bazar is owned by the descendents of these shareholders. The craft has been passed from one generation to another, and the community remains insulated over the ages through intermarriages within the community.

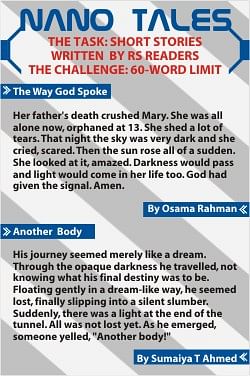

Shakha is primarily made from cutting conch shells into thin slices. The slices are shaped like bangles with a hole in the centre, and the artisans then carve it into a finer shape and cut through the designs. Often, one may find colourful stones or gold embedded within the intricate designs of the shakha and prices vary from as low as 200 taka up to 1500 taka.

Being a significant part of their culture and religion, shakha remains a sacred object. In the turmoil of the British Raj, partition between the Hindu and Muslim populations and socio-economic difficulties, shakha has carefully played an important role in adhering the Hindu community in Old Dhaka. In the age of neo-modern urbanizations, the Shakharis hold onto their heritage and habitat in spite of poor environmental and living conditions. The buildings are dilapidated or in danger of toppling down to ashes, while the government pays little heed to their demands. However, the community stays strong united and surprisingly content. The lavish lifestyles or fancy malls in New Dhaka rarely attract the Shakhari Bazar locals. Their hospitality, age old customs and communication between the families create an ambiance of bonding that they all love and enjoy. It is that small feeling of knowing your next door neighbour from the time you were one month old and growing up as part of a society that values its traditions and understands its people that hold the Shakhari community together through generations till date.

Reference: Star Weekend Magazine, 2006