|

|

|

Teach me not the unnecessary

Over the years, we have been taught numerous things, right? Well, it can be no surprise that when you look back over the years, you'll find tons of information which just cannot be applied in life. Taking hypothetical bread, if you consider the useless piles of information as general knowledge, your side of the bread is buttered. Other people, on the other hand, see all that uselessness as plain useless and so for our side of the hypothetical bread, all we see is mould. Hard to understand? Well, that's how it is for most people when you talk about algebra, geometry, cash flow statements and the works.

That's Not MATH

Find the log of what? Aren't log books supposed to be redundant? Haven't they been since the discovery of the calculator? Then how come some of us had to use it, meticulously I might add, for getting failing marks in our math tests? Logarithm isn't math and even if it is, it is hard to find it being applied in real life. It cannot also be applied in dream life or even the after-life. So, why are we doing it? Why have we done it?

People, generally speaking, know that they are not good at math. Why should there be useless topics to emphasize that understanding and humiliate the general populace? We pay almost tk.8000 to get an education and you give us algebra? Suppose I succeed in finding out the value of x, how is it going to help me in life? Would it put rice on my plate, a shine on my rims or a gleam to my suit? What is this algebra anyway?

An English Breakfast

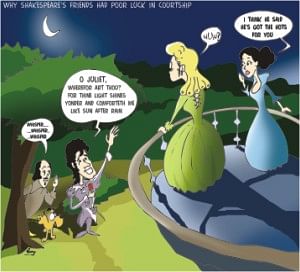

Have you ever wondered whether people during Shakespeare's time really spoke like that or not? Did they? Seriously? We have guessed not. And we have all read Shakespeare, one time or the other, but remember those unabridged books of his which we were taught when we were really small? You know, first class 'Learn the Alphabets' and the next period is 'Julius Ceasar'? I bet you remember those times. The teachers would go on and on saying 'Thous shanst manst planst' and we would be 'DUH'. There was really no point in pushing all those big words and complex sentences in our tiny heads. But, anyway, once we got accustomed to the language, ever had the experience of applying that language when writing an essay or giving an interview? I did and I got a minus thirty-five on my essay and I was laughed out of the interview. Apparently speaking Shakespearian doesn't work much these days. It didn't in those days too. Know why he was called a bard? Because he was bard (spell barred) from forever speaking in English. That was a funny joke cracked right there.

And The Miscellaneous

Then there was all the history. We don't know our history properly yet we want to rant on about Napoleon and his strategies. We don't know the current condition of the stock market, yet we know the poverty during the dark ages. Maybe its because that those that don't know history are doomed to repeat it, but what about those that don't know the present? Are they not doomed to destroying it? The present and the future? And fat lot of good it did, when one mess-up was replaced by his son a few years later, people knew history during the GWB times too didn't they?

Let's take a dig at Geography. Like we ever want to know how volcanoes explode. Or anything at all about the Earth's crust. Imagine applying for a job as an IT technician and your employer asks 'If you want this job, then tell me briefly about the earth's crust.' Can't even imagine it, eh? Been there, done that.

But in the end, in order to not shoulder the responsibility of the outcome of this piece, I accept all the things talked about above are needed. Sometimes to build basic and sometimes because the more we know, the better it is for us. However, equipping students for life after school is also necessary and schools can be a big help in this matter, by preparing students for their prospective careers, in the best way possible.

The author hopes to get a teaching job, so please don't take this too seriously if you are a prospective employer. Please.

By Osama Rahman

Carmilla

I will never be able to think of Carmilla without remembering the name Nietzsche. When she first came to live with her grandmother (to take care of her in her old age they said) down the valley, it never occurred to me- the impact she would have on me and my family. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Why Carmilla decided to stay on after her grandmother's death was a mystery to us and the townsfolk, but most of us seemed to be glad of it, so we never questioned her. She said she liked being closer to nature, and we ill had reason to doubt that.

'Once, we played in the forest, in the shade of the tall trees, in the dawn, of this particular time. But to me, an aeon has passed.

'She could skin deer better than me, which didn't do much for the growing envy I felt at someone who swooped down from a sprawling metropolis to live amidst wolves and fireflies. She asked me if I knew the difference between a shadow and a shade. I shrugged; she wouldn't tell me the answer for years to come. Not until the day she took me to the forest to decapitate me, would she say, “I grew up in the shadow; now I live in the shade.”

'Once, she failed to turn up for a hunt we had planned. I found out later that she was ill and I visited her house for the first time, with half the venison from the hunt cut prim and proper. She was on the bed, covered in a moth-eaten blanket with just her head sticking out. She wouldn't tell me what had happened, but I grew to know that Carmilla loved the sound of her own voice. She told me, “Man is something that ought to be overcome.” She said it was from the book she was reading that night, for the twenty-seventh time. I would know more about this man, Nietzsche, in the course of our friendship.

'At the time I had no idea how it was relevant to our conversation, but it became apparent when I started noticing changes in Carmilla. She spent the greater part of the harvest season that year in bed, with me sneaking her meat from our table every dawn. As my visits grew to be more and more frequent I began learning new things about Nietzsche. She used to laugh at my prayers for her speedy recovery, “A casual stroll through the lunatic asylum shows that faith proves nothing.”

'The next year on our hunt, Carmilla was faster and more nimble; taller even than me. But every now and then, months would come with her in bed, and I brought her sustenance during this time; it was an unspoken deal. In exchange she would educate me.

“Man is something that ought to be overcome,” she repeated during one of these regular visits, removing her blanket to offer me a full view of her two feet held together by iron shafts bandaged to them. She was breaking her own bones with a sledgehammer, and allowing them to re-grow. Every time her bones grew back, she would be taller, and less human. She made it apparent that the height wasn't the only change she was going through. That night she lent me a book, the first book that I wasn't forced to read: Human, All Too Human.

'I was told not to come see her for four fortnights. I was devastated, managing to find an apt enough thing to say, “But what will you eat?” She never smiled that smile again after that night, as she said, “I won't have to”, with a finality that left me no other option. During this time I read the book to tatters, and began to watch my father closely as he skinned deer. I needed to get better at it. And by the end of the time I did. Long moonlit nights I spent hunting deer, beginning to kill more than necessary, beginning to relish it. The moon afforded a shimmer on my blade that the sun scarcely did. Even blood looked different under moonlight. It was black, and it didn't seem to get on everything. I would leave the cadavers for bigger predators to clean up. Nature took care of itself. Carmilla would have been proud of my logic.

'When at the end of summer it was time, I rushed fast to her house and knocked, but she wasn't in. I waited the whole day, with growing unease. I came back every day for a week afterwards, till one day I found her sitting on a chair, reading. I called her from the window but she didn't move a muscle. I waited all night that night, till the moon came up and Carmilla walked out. I knew that things would never be the same again. She walked with a stoop, and a slight limp. She was wearing an oversized bearskin coat that reeked of putrid flesh and noticing the skilled knife work I had a strong suspicion how she came about it.

That night I got into her house and put the book back on the shelf. She never stopped me, walking on the porch in the moonlight in her less than human way. No, more. More than human.

'I was in love with her. I started to spend nights with her, reading the books in her library and looking at her. She didn't seem to be aware of my existence, moving with a memorized step, for she never looked. I wondered what she had undergone in the long time we had spent apart. I hated her for not letting me be a part of it.

'It took years for us to fall back into regular life. In her own pathetic state she would go into the forest, and just stand, sometimes walk or sit. I would slaughter game after game, bringing her the corpses, letting her know it was all for her. It came as a surprise when she began to start taking her hunting knife with her again. It had accumulated a fair amount of rust, but I suspected she meant to do much hunting with it. She just liked having it around. When my father died, I opted to hunt instead of attending his funeral. Carmilla was still unaware of me, by now literally living with her in the same house, but the hunts were the most involved we were in anything together.

'The last thing Carmilla said to me was “I won't have to”. On one of our regular hunting trips under the full moon, as I was flaying the flesh of a dying deer, sick of not finding bigger game, Carmilla snuck up behind me with her hunting knife, aimed with her expert skill for my neck. Her fragrance of rotting bear flesh and dried blood met my nostrils, piercing through the thick winter's mist. Nietzsche would classify us humans as slave moralists, or master moralists. Slave moralists went with the herd, but master moralists knew that all which was good was what heightened the feeling of power. Carmilla taught me the concept, before her drive to become more than she was born as, more than human.

I clutched hard the broken deer rib that was still on my bloody hand, and swinging around I stuck it far up into her head through her throat, feeling it come and rest at her cranium. Blood sprayed forth under the beautiful full moon night. Black blood. Not a syllable escaped Carmilla's lips, as she fell forwards into my embrace. We lay together in the forest till dusk.

'Once, we played in the forest, in the shade of the tall trees, in the dawn, of this particular time. But to me, an aeon has passed.'

With his final words uttered, he brought out the blade he hadn't bothered to conceal much in the first place. The girl was younger than usual, and she was a tourist. He knew it was risky, but it was riskier to use anymore people from the village, considering its small size.

'“I won't have to” were the last words I heard Carmilla say. I loved her. You know, you look a lot like her. And unlike her, I will have to. I don't do this just for fun; it's a need that I feel. I'm sorry.'

With that, he slit her throat, letting the blood spray his face. He had found bigger game. And unlike Carmilla, he had overcome his humanity.

By Ahsan Sajid |

|