35

Years of YES

By

Craig Rosen

NEW

YORK (Billboard) - "It's the most positive word in the English

language," Yes drummer Alan White says of his band's moniker.

Beyond that, Yes

is a classic-rock institution that has thrived for the better part

of three decades, since forming in 1968 in Birmingham, England.

As Yes prepares

to return to U.S. arenas on the heels of the release of "The

Ultimate Yes -- 35th Anniversary Collection," Billboard caught

up with all five members of the group before they converged on a Los

Angeles studio to record material for a bonus disc to be included

with the American version of the retrospective. A new studio album

is planned for next summer.

Q: In

your wildest dreams, did you ever think Yes would celebrate its 35th

anniversary?

Jon Anderson (Vocals

and founder): Two or three years was the maximum in those days, or

two or three minutes, depending on what the day went like. When we

started, we really wanted to be as good as a band called Family. They

were doing the clubs. That's all we wanted -- to get as big as that,

and probably do some university gigs. You never think you're going

to have success. It just comes upon you, and that's when you count

your blessings, because a lot of people don't get that success.

Steve Howe (Guitars):

The '70s were quite an achievement. When that finished and I formed

Asia with John Wetton, I really felt that was then, and now I was

going to keep doing different things. But by the time I had Asia and

GTR Steve Hackett, I started to realize that the Yes music of the

'70s was great.

Chris Squire (Bass

and founder): I was 15 when the Beatles came to light around '63.

That's kind of what got me interested in the whole profession. At

that time, a long career in my eyes was like the Beatles, '63 to '69

-- six years. I thought, "Wow! Wouldn't it be great to be in

a band that had a six-year career?" I never ever thought at some

point together 35 years, because there was no blueprint for that.

Rick Wakeman (Keyboards):

In my various ins and outs, I've been around for about a third of

the life of Yes. In the '80s, many of the classic bands dismantled

themselves or took incredibly long sabbaticals.

Alan White (Drums):

I joined at a very early time the band was only 3 years old. In joining,

I gave the band three months to test our styles out and whether I

would enjoy playing with the band and them with me. And here we are

about 31 years later.

Q: The

band's history has been rather soap opera-like, with all the personnel

changes. What were the low points?

Anderson: We've

all had our moments. It's always been a question of, "Are you

into where we're going? If you're not, you should leave." We

didn't all come from the same town, so we didn't feel like we were

bound together with an umbilical cord.

Wakeman: The low

points to me were certainly around the "Topographic Oceans"

era. I couldn't get into the direction the music was going, and Yes

is always a give-and-take. Having to make the decision to leave, that

was a low point.

Q: What

do you consider the highlights of the band's career?

Anderson: There

are about three or four. The time when we initially became famous

in England, and we played with Cream at their final concert at Albert

Hall. That was like a dream. Also when we did "Close to the Edge."

The scope of doing a piece of music like that and having an audience

that would listen to it was a great feeling.

Another highlight

was when we had a resurgence in the early '80s with "90125";

that was a very big leap into being famous for 10 minutes. We had

a No. 1. We were treated like rock stars. A week into that tour, I

went with this young filmmaker, Steve Soderbergh, to see "Spinal

Tap." I went in and saw my whole world in front of me. It blew

my mind. I never laughed as much in my life. I could never take myself

seriously again.

Howe: "Close

to the Edge" was the invention of the 20-minute Yes, and it stands

because of that. We were challenging the idea that we could play 18-plus

minutes at a time. Jon and I were so excited to have this sort of

symphonic approach to our music. We did "Roundabout," which

was quite a long song, and then we sat around with these smirks on

our faces as the songs started to expand. I started playing Jon some

ideas, and we realized we were going to invent something really big.

The next time

we hit it was when Rick returned and we did "Going for the One"

album. We were still in this wonderful pre-digital time when there

was marvelous warmth. Listening to that guitar at the beginning of

"Turn of the Century," I was feeling every moment of it.

Wakeman:

The highlights to me were certainly the "Fragile"/"Close

to the Edge" years -- '71, '72 and early '73 -- because I thought

the balance in the music business was perfect. Bands were left alone

to create music. Nobody told us what to play, how to play, how to

record. We were the musicians, the scientists in the lab.

a

brief history of YES

Yes was the quintessential English art-rock band,

with all the excess and all the glory that entails. Loaded with too

much virtuosity, too many ideas and too many personnel changes for

one band to deal with, Yes has produced its share of spotty albums

over the past 20 years. Yet during its classic period lasting between

1970's The Yes Album and 1977's Going For The One Yes was almost consistently

inspired. Anyone needing to defend art-rock only has to pull out the

side-long title track of Close To The Edge (1972): It never got more

visceral or more melodically soaring than that.

Initially Yes was simply a pop group that got very,

very ambitious. Their first two albums have some R&B traces, thanks

to the more basic styles of guitarist Peter Banks and keyboardist

Tony Kaye, who both got weeded out early. Yet the delicate, almost

feminine tones of singer Jon Anderson proved an early trademark, along

with the jazz leanings of the rhythm section (bassist Chris Squire

and drummer Bill Bruford, replaced in 1972 by the heavier-hitting

Alan White).

With

the arrival of guitarist Steve Howe and keyboardist Rick Wakeman,

Yes was free to explore the rock-symphony approach they aspired to.

Their ambitions reached a peak on 1973's Tales From Topographic Oceans--a

four-song, lyrically dense double album that even Wakeman found excessive

(he exited for a year, replaced by Patrick Moraz)-- yet there were

more than enough lovely and powerful moments to justify the stretch.

Reunited with Wakeman after a year making solo albums, Yes stripped

down to relative basics and made its last great album with 1977's

Going For The One.

With

the arrival of guitarist Steve Howe and keyboardist Rick Wakeman,

Yes was free to explore the rock-symphony approach they aspired to.

Their ambitions reached a peak on 1973's Tales From Topographic Oceans--a

four-song, lyrically dense double album that even Wakeman found excessive

(he exited for a year, replaced by Patrick Moraz)-- yet there were

more than enough lovely and powerful moments to justify the stretch.

Reunited with Wakeman after a year making solo albums, Yes stripped

down to relative basics and made its last great album with 1977's

Going For The One.

Since then the band's inability to settle on a permanent

lineup, coupled with the inevitable career fatigue, has kept them

from hitting the same peaks. Anderson and Wakeman left in 1979, replaced

by the two members of the Buggles (the resulting album, Drama, was

nowhere near as bad as it could have been).

Yes was then laid to rest until 1983, when Anderson,

Kaye, Squire and White formed a new lineup with guitarist/singer Trevor

Rabin. At first Rabin's mainstream instincts were just what the band

needed--the 1983 album 90125 was both creative and commercial, if

not quite the cosmic Yes of old--but wound up taking far too much

control and made Yes sound too ordinary.

Anderson

rebelled and pulled in the other ex-members for a competing band,

clumsily billed as Anderson, Wakeman, Bruford, Howe--but that didn't

work either, thanks to overdone production and spotty material. The

nadir came when some unfinished AWBH demos were cobbled together with

some Rabin outtakes as a Yes album, Union; an eight-man lineup cashed

in with a reunion tour. The closest thing to a real comeback happened

when the Topographic Oceans lineup reunited in 1996 for Keys To Ascension,

a live album of great Yes obscurities, plus a surprisingly solid studio

section (two new songs totaling 30 minutes, their first long suites

in years). Ever since the band released a couple of studio albums

and continues to hit the road.

Call

of Duty

Gamespot

Rating: 9.0. Difficulty: Medium. Learning Curve: about a

half-hour. Stability: stable. Version: Retail. Publisher: Activision.

Developer: Infinity Ward. Genre: Action. Release Date: Oct 10. Requirements:

128 MB RAM, 8X CD-ROM, 32 MB VRAM, 1400 MB disk space, DirectX v9.0.

There is no shortage of World War II-themed first-person

shooters available, and it's no secret that a number of them, including

Medal of Honor: Allied Assault and Battlefield 1942, are extremely

good. Now you can add Call of Duty to that list.

The first game by Infinity Ward, a studio composed

of some of the same team that worked on Allied Assault, Call of Duty

presents outstanding action all around and is at least as good as,

and in several ways is simply better than, any similar game. Though

both its single-player and multiplayer modes will be familiar to those

who've been keeping up with the WWII-themed shooters of the past several

years, most anyone who plays games would more than likely be very

impressed with Call of Duty's authentic presentation, well designed

and often very intense single-player missions, and fast-paced, entertaining

multiplayer modes.

This

is a game that pulls together many of the best aspects of other, similar

games, and also includes all sorts of little "wish-list items"

that may have crossed your mind while playing those other games. The

result seems, above all, very well designed. The action in Call of

Duty, ultimately, is arcadelike--much like in Allied Assault or Battlefield

1942. You can't survive a shot to the head, but you can take a few

bullets anywhere else and can keep going just fine. There's also a

clear onscreen indication of the direction from which you're taking

fire (and, as you're getting hit, the screen shudders to make it look

like it hurts). Luckily, first aid kits, conveniently placed in the

levels or occasionally dropped by killed enemies, instantly restore

large portions of your health. You hardly ever need to activate a

"use" key in this game. When you do, you'll use it to instantly

set explosives or grab documents, but you won't use it for opening

doors.

This

is a game that pulls together many of the best aspects of other, similar

games, and also includes all sorts of little "wish-list items"

that may have crossed your mind while playing those other games. The

result seems, above all, very well designed. The action in Call of

Duty, ultimately, is arcadelike--much like in Allied Assault or Battlefield

1942. You can't survive a shot to the head, but you can take a few

bullets anywhere else and can keep going just fine. There's also a

clear onscreen indication of the direction from which you're taking

fire (and, as you're getting hit, the screen shudders to make it look

like it hurts). Luckily, first aid kits, conveniently placed in the

levels or occasionally dropped by killed enemies, instantly restore

large portions of your health. You hardly ever need to activate a

"use" key in this game. When you do, you'll use it to instantly

set explosives or grab documents, but you won't use it for opening

doors.

Actually, that's because you won't be opening any

doors. One gameplay contrivance that's presented in the first few

seconds of the first mission is that any time you see a closed door

in Call of Duty, it's supposed to stay closed. This seems like a minor

point, but how many shooters have you played in which you fumbled

for every doorknob, trying to find the one door that would actually

open? That's simply not an issue in Call of Duty. Despite the highly

authentic atmosphere created for the levels in the game, there tends

to be an intuitive, clear path from the beginning of the level to

the end. The levels can be challenging, at least at the higher two

of the game's four difficulty settings, but they're not frustrating.

If you die, you can restart at your most recent save almost instantly.

You don't need to worry about hitting the quick-save key all the time,

either, since the game automatically and seamlessly saves your progress

not just at the beginning of a level but at several points throughout

the level. The game's brief tutorial at the beginning of the single-player

mode will be second nature for experienced players of first-person

shooters. However, since it's in the context of a military boot camp,

it will also provide, for new and experienced players alike, some

valuable advice on (and practice with) the nuances of Call of Duty's

gameplay.

You cannot sprint in Call of Duty, nor can you tiptoe.

While standing, you move at a constant pace that's not too slow and

not too fast but is just right. You'll have no trouble quickly getting

from point A to point B. However, when you're running from cover to

cover in an area that's under fire, you'll be painfully aware of how

vulnerable you are. You should probably keep your head down, and Call

of Duty lets you easily switch between standing, crouching, and prone

stances. You move slower while crouching--not too slowly though--which

makes this the best way to get around when in the thick of battle.

Movement, as well as turning, is understandably much slower while

prone. Sometimes, however, this is the perfect option for staging

an ambush or staying out of harm's way. As in many shooters, you can

also lean around corners in Call of Duty, which can be a real lifesaver

during some of the game's deadly firefights when you need all the

cover you can get.

Call

of Duty features a wide arsenal of authentic American, British, Russian,

and German WWII weapons, including various rifles, submachine guns,

side arms, and grenades. You can carry only two larger weapons at

a time (as well as a pistol and some grenades), so, typically, you'll

want to have a rifle for out-in-the-open engagements and a submachine

gun for tight-quarter combat. While armed with any of these, you may

shoot from the hip, raise the weapon to eye level and aim down the

sight (for more accuracy at the expense of movement speed), or use

the butt of the weapon to try and club an enemy to death. Manually

reloading your weapon tends to be faster than letting the clip run

out, and some weapons let you switch firing modes, like going from

full-auto to single shot (though, since you can squeeze off single

rounds in full-auto mode, this isn't very useful). Your crosshairs

expand when you're moving and contract when you're steady, pointing

out how much more inaccurate you'll be if you try to run-and-gun.

The weapons themselves are modeled very convincingly, thanks in no

small part to the tactile sense you get from being able to look through

their sights or use them as bludgeons, and most every one will earn

your respect since, in the right situations, they can all be deadly

effective.

Black

Music

By

Synergie

Black

magic is a term that has been known and practiced for many centuries.

But Black music…? Don't get worried, it's not another unearthing form

the depths of dark arts. It's actually something, well… 'out of this

world'.

Black

magic is a term that has been known and practiced for many centuries.

But Black music…? Don't get worried, it's not another unearthing form

the depths of dark arts. It's actually something, well… 'out of this

world'.

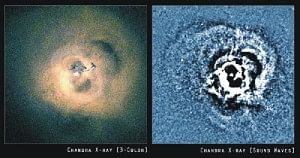

Astronomers using

NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory have found, for the first time, sound

waves from a super-massive black hole. The "note" is the

deepest ever detected from any object in our Universe. The tremendous

amounts of energy carried by these sound waves may solve a longstanding

problem in astrophysics.

The black hole

resides in the Perseus cluster of galaxies located 250 million light

years from Earth. In 2002, astronomers obtained a deep Chandra observation

that shows ripples in the gas filling the cluster. These ripples are

evidence for sound waves that have traveled hundreds of thousands

of light years away from the cluster's central black hole.

Earlier observations

had revealed the prodigious amounts of light and heat created by black

holes. And now, scientists have detected their sound, too. In musical

terms, the pitch of the sound generated by the black hole translates

into the note of B flat. But, a human would have no chance of hearing

this cosmic performance because the note is 57 octaves lower than

middle-C. For comparison, a typical piano contains only about seven

octaves. At a frequency over a million billion times deeper than the

limits of human hearing, this is the deepest note ever detected from

an object in the Universe.

"The Perseus

sound waves are much more than just an interesting form of black hole

acoustics. These sound waves may be the key in figuring out how galaxy

clusters, the largest structures in the Universe, grow." says

Steve Allen of the Institute of Astronomy.

For

years astronomers have tried to understand why there is so much hot

gas in galaxy clusters and so little cool gas. Hot gas glowing with

X-rays ought to cool because X-rays carry away some of the gas' energy.

Dense gas near the cluster's center where X-ray emission is brightest

should cool the fastest. As the gas cools, say researchers, the pressure

should drop, causing gas from further out to sink toward the center.

Trillions of stars ought to be forming in these gaseous flows.

For

years astronomers have tried to understand why there is so much hot

gas in galaxy clusters and so little cool gas. Hot gas glowing with

X-rays ought to cool because X-rays carry away some of the gas' energy.

Dense gas near the cluster's center where X-ray emission is brightest

should cool the fastest. As the gas cools, say researchers, the pressure

should drop, causing gas from further out to sink toward the center.

Trillions of stars ought to be forming in these gaseous flows.

Yet scant evidence

has been found for flows of cool gas or for star formation. This forced

astronomers to invent several different ways to explain how gas contained

in clusters remained hot. None of them were satisfactory. Black hole

sound waves, however, might do the trick.

Previous Chandra

observations of the Perseus cluster reveal two vast, bubble-shaped

cavities extending away from the central black hole. These cavities

have been formed by jets of material pushing back the cluster gas.

The jets, which are a counter-intuitive side effect of the black hole

gobbling matter in its vicinity, have long been suspected of heating

the surrounding gas. But the exact mechanism was unknown. The sound

waves, seen spreading out from the cavities in the recent Chandra

observation, could provide this heating mechanism.

A tremendous amount

of energy is needed to generate the cavities, as much as the combined

energy from 100 million supernovas. Much of this energy is carried

by the sound waves and should dissipate in the cluster gas, keeping

the gas warm and possibly preventing a cooling flow. If so, the B-flat

pitch of the sound wave, 57 octaves below middle-C, would have remained

roughly constant for about 2.5 billion years.

Perseus is the

brightest cluster of galaxies in X-rays, and therefore was a perfect

Chandra target for finding sound waves rippling through the hot cluster

gas. Other clusters show X-ray cavities and future Chandra observations

may yet detect sound waves in those clusters, too.