| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 12 |Issue 07| February 15, 2013 | |

|

|

Special Feature PUNISHMENT < CRIME Tamanna Khan

Silence has been the typical response people have shown to all kinds of injustice in our society for 42 years until the afternoon of February 5, 2013. Like a fairy tale wand, a single verdict seems to have awakened people. For the first time they raised their voice in unison against the culture of impunity that has started to grow its roots in the country since the trial of the war criminals were aborted 39 years ago. After the Liberation War, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had started the trial of the war criminals who collaborated with the Pakistani Armed Forces and carried out heinous crimes against their own fellow countrymen. The criminals were mostly members of auxiliary forces such as Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams, formed by right-wing political parties of which Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan was a main player. Since the Collaborators Order 1972 had limitations, the International Crimes (Tribunal) Act, 1973 was enacted to try internationally defined crimes committed in 1971, such as mass killing, rape, genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. In spite of all these developments, the road to justice was blocked with the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The trial of the collaborators, who did not fall under the general amnesty declared by Bangabandhu on November 1973, came to a sudden end and everyone was freed as the post Mujib government scrapped the Collaborator's Act. Thus began Bangladesh's dark and shameless chapter of promoting the culture of impunity. While the survivors, victims and their families continued to cry for justice with support from organisations such as the Ekkaturer Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee, it took a completely new generation to convince our political leaders of the necessity of resuming the trial of the war criminals. In 2008, they used their legal, democratic right and voted the party that promised the trial, to power. The Awami League led grand alliance government formed the International Crimes Tribunal on March, 2010 and the first trial began on July, 2011. Since the beginning of the trial, the law was criticised by the defendants, which was also supported from a section of the international community, claiming that the law does not give enough right to the defendants. Both Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) continued to campaign against the trial calling it “politically motivated” since most of the accused are top-notches of the JI, BNP's chief political ally. Initially, JI continued its fight in the legal field. As the trials began to close, their activities took a violent form. People watched in quiet apprehension as Jamaat burned vehicles, carried out sudden attacks on law enforcement agents and even threatened civil war – all to save the alleged war criminals who committed heinous crimes as rape, murder and genocide. Yet people kept mum until the sentence of life imprisonment was passed on Abdul Quader Mollah, one of the most notorious collaborators known to the residents of Mirpur as Mirpur's Butcher.

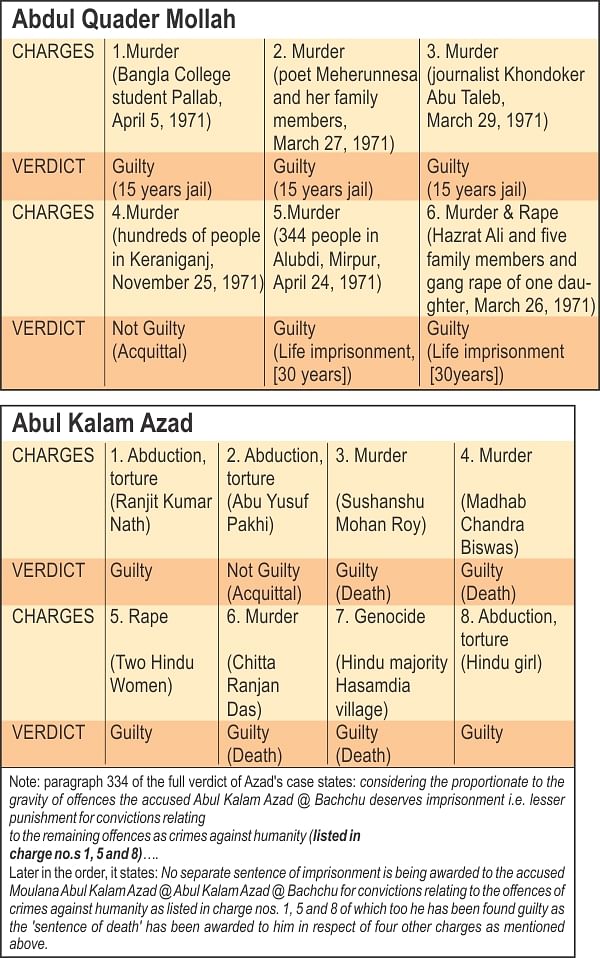

Mollah, assistant general secretary of the JI, was found guilty of two murder charges and complicity to murder in three other chargers, under crimes against humanity. In one charge, Mollah was found guilty of mass murder of 344 people of Alubdi, Mirpur. Yet he was given life imprisonment instead of a death sentence. Mollah's verdict is not the first, delivered under ICT Act, 1973. In January 21, 2013, the absconding Abul Kalam Azad alias Bachchu Razakar was given death sentence for six charges related to crimes against humanity and one for genocide. From a layperson's point of view both Mollah and Azad are proven criminals carrying out offences of almost equal gravity, why then would the former receive a less harsh sentence than the latter? Section 20 (2) of the International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973 states: Upon conviction of an accused person the tribunal shall award sentence of death or such other punishment proportionate to the gravity of the crime as appears to the tribunal to be just and proper. Prosecution lawyer Rana Dasgupta, says, “Section 20(2) says that if punishment is to be awarded for the crime that has been proven then first he should be given sentence of death. If the person is given any other punishment as alternative, in that case it has to be explained why the person was not awarded death sentence.” Dasgupta refers to Section 20(1) in which the tribunal is required to give reasons behind a judgement. He adds that the tribunal should have included a paragraph in the 132-pages verdict of Mollah's case, the reason for awarding a sentence other than death penalty. “The very reasoning of the decision is absent,” Dasgupta criticises. A similar question is raised by Professor Asif Nazrul of the law department, University of Dhaka. Referring to the principle of common intention, he says, “There was a common intention behind mass killing or genocide of the 344 people in the Alubdi village. All of them (Mollah and his cronies) have contributed to the execution of the common intention. Therefore, he should have received capital punishment.” He says that in case of paralysed persons or persons above the age of 90 years, the judges can award alternate punishment highlighting his/her ill-health or senility as the reason. Interestingly, in Azad's verdict, the tribunal clarifies why no lesser punishment has been awarded to him. In the 132 page verdict of Mollah's case both a greater (life imprisonment) and a lesser sentence (15 years) has been awarded, without explaining the need for the latter. The prosecution lawyers remain baffled as to on what basis the tribunal judges awarded such a sentence. Prosecutor Mohammad Ali says that the prosecution team was expecting order of death sentence throughout the tribunal. But they have been let down at the last moment. Referring to Charge no- 6 brought against Mollah for killing Hazrat Ali and his family and gang-raping one of his daughters, the agitated prosecutor says, “We have brought the other daughter who escaped the atrocity to the witness stand. She is an eye-witness and a victim. If death sentence is not awarded to such a case, then I do not think there can be any other incidents in the world which even after being proven would not qualify for death sentence.” According to Dr MA Zahir, Barrister-at-law and senior advocate of the Supreme Court, ‘there is no objective standard' of punishment. He explains that the sentence for a crime in general depends at the discretion of the judge. Barrister Tureen Afroz, associate professor of law at Brac University, explains a little further saying that a judgement depends on the strength of the information, evidence and witness presented in the court of law. “It is true that murder charges were brought against both of them,” she says referring to Mollah and Azad's cases, “Perhaps the liability of one of the accused could not be proved to the same extent as it was in the case of the other.” She says that although both of them were convicted of crimes against humanity, the extent of their involvement might have been different, which may lead to a difference in verdict.

Barrister Afroz notes that in Mollah's case the charge of 'superior or command responsibility' has not been brought. “In Bachchu Razakar's case it can be noted that he committed most of the crimes under individual responsibility but if 'superior responsibility' could have been brought in Quader Mollah's case then it would have ensured death sentence,” she says mentioning that Mollah was President of Dhaka University's Shahidullah Hall's Islami Chhatra Shanga (student wing of the then Jamaat-e-Islami) in 1971. Prosecutor of Mollah's case Mohammad Ali explains why Mollah was not charged under this particular liability. Stating the dates of the crimes with which Mollah was charged, Ali clarifies how (except for November 25 related to charge-4 for which Mollah got acquittal) these particular offences were committed before the formal establishment of the auxiliary forces that collaborated with the Pakistan Army. Therefore, Mollah committed these offences in individual capacity and was charged as per Section 4(1) of the Act which states: When any crime as specified in section 3 is committed by several persons, each of such person is liable for that crime in the same manner as if it were done by him alone. As the debate around Mollah's verdict continues, Dr Zahir advises that the government should appeal to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh against the acquittal order passed on Charge no 4 of Mollah's case, as soon as possible. Ali informs that they are getting prepared to appeal against the acquittal. “Regarding enhancement of the inadequate sentences, that is life sentence, we shall appeal for complete justice under Section 104 (of the Constitution),” he says. Referring to the Supreme Court's authority of ensuring complete justice, Dr Zahir says that there is no guarantee that Supreme Court will use this power, which under normal circumstances is very rarely applied. Regarding the proposed amendment to the ICT Act, 1973, wherein the state will get the opportunity to file an appeal with the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court against any sentence that did not meet people's expectations in war crimes cases, Afroz opines, “Does the chance for appeal guarantee death penalty? If the case is weak then who can guarantee you that death sentence will be passed once you appeal?” Under the circumstances, Afroz suggests that while keeping the appeal option open, prosecution should files new charges against Mollah, this time with stronger evidence and paperwork. As a member of Ekatturer Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee, she feels that a stronger prosecution team is needed. “Based on our observation of 2011 and 2012, there is a lack of coordination between prosecution and the investigation team,” she says. However, prosecution member Ali denies allegations of any such inefficiency.

The defence are in a better position considering the limitation of appeal that currently exists in ICT Act 1973. However, Barrister Abdur Razzak, chief defence counsel still insists that the said law is unfair towards the accused. He says that when the international community observed that the law did not meet international standards, the government did not change it. “Now they are apparently in difficulty because of the verdict given by the tribunal. Now they want to change it to their advantage,” he comments, “Who said that the law is not fair for the victims? The minister (law minister) said so. He is a partisan man.” The people of Bangladesh, the families of the martyrs and victims of 1971, the thousands others who survive with scars from the atrocities of '71, of course do not feel the same way as Barrister Razzak does. They feel their expectation of justice has not been met in the verdict of Abdul Quader Mollah's case. So they have taken to the streets and unlike the activists of Jamaat-e-Islami and Islami Chhatra Shibir, they are asking for a change in law peacefully. It is through a legal process that we have to find a way of ensuring justice for all. |

||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2013 |