| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 12 |Issue 03| January 18, 2013 | |

|

|

Profile MEMOIRS OF A FRIEND Zahir Hassan Nabil

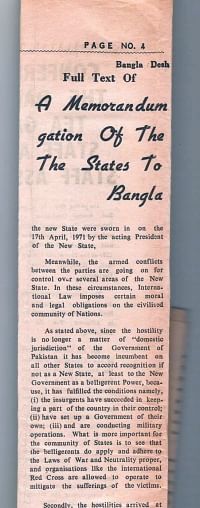

Sometime in 1971 US President Richard Nixon had a memorandum in his hand that narrated how the Bangalees were systematically being killed by the Pakistani occupation forces from March 25 onwards. The invaluable document argued in the light of International Law that the killing must be considered genocide and thus called for immediate international intervention to stop the bloodshed in what the world at that time knew as the East Pakistan. The historic memorandum was penned by Barrister Abdus Salam in Calcutta. An Indian citizen in his eighties, Barrister Salam has recently been honoured with the accolade of Friends of Liberation War Honour [Muktijuddho Moitri Samman-ana] along with 61 other friends of Bangladesh in December last year in the capital. On a winter morning Barrister Salam took the trouble to recollect his memories of the Liberation War as he was recuperating from a heart attack just after arriving in Bangladesh, to receive the award, “My friend Barrister Robindra Nath Das had once studied with one of the staffers of President Nixon. He helped the memorandum to reach the president. Barrister Das later wrote to me that the president had said that it was not possible to take any action against the atrocities.”

“Later, I assumed, Nixon said as such because he was in favour of West Pakistan. At the same time, the then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was going incognito to China to negotiate peace through Pakistan to end the Vietnam War,” he ponders. Interestingly, Barrister Salam's assumption proved to be true word-for-word four decades after the Liberation War. In March 2012, an India Today report quoted Kissinger admitting that the war broke when the US was negotiating with China through Pakistan and it was the national interest of the US to preserve West Pakistan. So how did it all begin? “Originally from Jinjira in Old Dhaka, I had been living in Dhaka and Calcutta throughout my college years,” says Barrister Salam, sitting in a cosy couch corner in his brother's living room. He had known Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman since his days as an intermediate student at Islamia College (now Maulana Azad College) in Calcutta, after passing matriculation exams from Dhaka College in 1946. “I used to live on the upper floor of Baker Hostel of the college, Mujib bhai was on the ground floor, then preparing for his BA finals. He had a soft corner for me as I used to pray five times a day and was from a very religious family. In the college, the comparatively 'naïve' Bangalees were bullied by the 'smarter' Urdu-speaking students of Calcutta. The first time I heard Mujib bhai speaking was on the hostel's courtyard in a meeting to settle the bullying.” Barrister Salam's paternal grandfather Khan Bahadur Hazi Hafez Muhammad Hussain (1855 -1939) was a prominent educationist of his time who set up the Hussainia Ashraful Uloom madrassa in Bara Katra and pioneered girls' education in Jinjira by setting up a girls' school. He was mentored by scholars like Dr Muhammad Shahidullah and Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanwi. Hafez Hussain gave out many of his properties as Waqf estate, a trust for charitable purposes under Islamic Law. Salam came to Dhaka to do his graduation after the partition of the Indian subcontinent and looked after the portion of Waqf estates in Dhaka (the rest in India) that gave scholarships for students and contributed to other charitable purposes. It was by then he again met Bangabandhu in Dhaka. Barrister Salam reminisces, “In the early 50s, Mujib bhai was involved in student politics. Whenever he used to come to Jinjira for campaigning, he used to take me with him. He had a very sharp memory and could resume conversation years after meeting someone. I was in Dhaka around 1954 when the East Pakistan Legislative Assembly general election was held. The Bengalis won defeating Pakistan Muslim League.” Salam then went back to Calcutta in 1956 and got admitted for an MA and subsequently went to study law at Lincoln's Inn in London. “I had taken a bit of time than usual because I used to take long breaks and visit Europe every year. Then I returned to Calcutta and took Indian citizenship,” he recalls. Barrister Salam narrates his experiences at the time of the War, “The chaos was just brewing when I went to Dhaka in 1969 before the Liberation War. Then in Calcutta we heard Mujib bhai's racecourse speech on the radio. After March 25, hearing the news of Pakistani atrocities in the city, I got very worried about my family in Dhaka; Jinjira was under attack on April 3. I had known only one contact in Calcutta, Mustafa Monwar, the son of poet Golam Mustafa, who used to keep me updated of the news from Dhaka and that my family was alright.”

Just after the war broke, Barrister Salam sheltered hundreds including intellectuals and now eminent personalities in Bangladesh at his Palm Avenue residence in Calcutta. Journalist Sadek Khan, Barrister Moudud Ahmed, Bangla Academy director late Syed Ali Ashraf, the then lawmaker Subid Ali Tipu were among the ones who stayed at his place throughout the war, acknowledges HT Imam, the public administration affairs adviser to Sheikh Hasina, in his book Bangladesh Sarkar 1971. A footnote in the book reads, “Mr Salam greatly contributed to the Liberation War. His Palm Avenue House was a refugee camp. Hailing from Dhaka [Salam was] empathetic to the Liberation War; whoever arrived was given shelter [by him]. Moreover excellent accommodation and food were provided in his spacious apartment, people rested on the floor or couches when beds ran out.” The Barrister adds, “Every day a few arrived in my house. I also used to go out whenever I heard someone came to Calcutta. Until the Indian government had set up an ad hoc headquarters after the arrival of Tajuddin Ahmed, many meetings were held in my house. Salam shares in a trembling voice, “I wanted them to go out and let the world know what was happening in Bangladesh.” It was the time he wrote the memorandum, “I didn't dare to publish the document from Calcutta because I feared if it became known, it might have a repercussion on my family and relatives in Jinjira. So I had it published from Nepal,” recounts the Barrister. He sent it out with whoever was going out to different countries including the US, UK, Sweden, France and Holland – to name a few. Salam's eyes glow and voice shudders as he stresses, “We were determined to have the Pakistanis out of the country and we had it accomplished. People must have such determination against any injustice”. It was fortunate to have the barrister for a conversation as he now visits Bangladesh less frequently after his mother passed away in 1988. Despite hearing from Bangladesh after four long decades of silence, this humble friend of Bangladesh wholeheartedly thanked everyone. “I am particularly grateful to the Awami League government for remembering me and sending the invitation,” he says.

|

||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2013 |