| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 47| November 30, 2012 | |

|

|

Health STOP Impostor! Katie Lambert

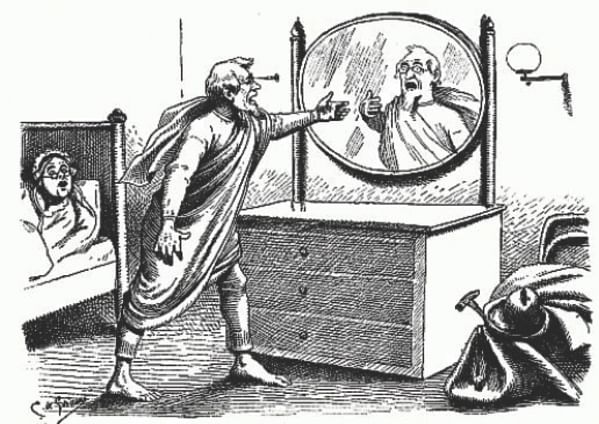

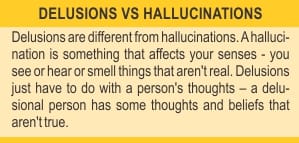

Your father comes in the door and you go to greet him. Suddenly, you stop. Why, this man isn't your father at all. He looks like your father, but no, you decide, that definitely isn't him. He's been replaced by an impostor! Capgras syndrome is what's known as a delusional misidentification. It's the opposite of déjà vu. People with Capgras syndrome think that their spouse, family members or even their pets have been replaced with doubles. Imagine how disconcerting it would be to have someone who looks like a loved one sit down with you and know intimate details about your life, even though you're sure that this person is a trickster. Capgras syndrome used to be considered very rare, but medical professionals are beginning to think that perhaps it isn't so rare after all. The more doctors that know about it, the more people they find who have it. Capgras was first described by two French doctors, Joseph Capgras, for whom the syndrome is named, and Jean Reboul-Lachaux. Their patient, Madame M, was convinced that her family and neighbors had all been replaced by look-alikes. She said she'd had 80 husbands – one impostor would simply leave to make room for a new one. Capgras syndrome isn't the same thing as face blindness, or prosopagnosia. People with prosopagnosia can see a face for the hundredth time and still not know who it is. You can walk right by your best friend and not recognise her even when she says hello. People with prosopagnosia, however, show changes in their skin conductance when shown a picture of someone they know. Part of their brain recognises this person emotionally, even if consciously they don't know who it is. People with Capgras syndrome can perceive faces, and recognise that they look familiar, but they don't connect that face with the actual feeling of familiarity. That woman looks like your wife, but you don't feel that she really is your wife. You don't have the feelings you should have when you look at this person with your wife's face. Their skin conductance stays the same as it would if they were looking at a total stranger. It's a problem of disconnection. So what's going on? There are a few theories as to how Capgras syndrome works, some of them likelier than others. The psychoanalytical view is that perhaps the syndrome is a result of an Oedipus or Electra complex – sexual desire for one parent, sexual jealousy for the other. People with the syndrome must be trying to resolve their guilt about these circumstances by identifying their parent as a parental look-alike. Some psychodynamic theories propose that Capgras syndrome has to do with repressed feelings. The psychodynamic approach, however, has been mostly discredited.

Many researchers think that Capgras syndrome is actually the result of something wrong with the brain, an organic cause. They look for lesions on the brain, signs of atrophy and other cerebral dysfunction. Although Capgras syndrome is usually seen in people who have psychotic disorders, more than a third of Capgras patients have signs of head trauma. Many Capgras patients also have other organic conditions, like epilepsy or Alzheimer's.

Somewhere, the brain isn't communicating when it should be. This breakdown of communication might be happening between the part of the brain that processes the visual information for faces and the part that controls the limbic system's emotional response. The argument seems to come down to whether Capgras syndrome is a problem of perception or of some other process, like memory. Hirstein and Ramachandran proposed that Capgras syndrome is a problem of "memory management." They give this example: Think of a computer. You make a new file and save it. When you want that information, you open the old file, add to it, save and close it again. Perhaps people with Capgras keep creating new files instead of accessing the old one, so that when you leave the room and re-enter, you are a new person, a person who looks like the one who left, but slightly different – maybe your ears look bigger, or your hair a different hue. There's still a lot that science doesn't know about the human memory.

Some studies have also shown blind people with Capgras syndrome – their delusion extends to the voice of a person, thinking that the voice is a voice of an impostor, instead of the face, so perhaps it isn't a face-processing problem at all. Other studies have shown people who were convinced by looking at a person that that person was an impostor, but they recognised the person's voice on the phone. Other Delusional Misidentification Syndromes Frégoli syndrome or Frégoli delusion Cotard's syndrome or Cotard's delusion

Déjà vu Source: http://science.howstuffworks.com

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |

Still more doctors and researchers combine the idea of both a physical and a cognitive cause. There's something wrong with the brain, but why and how is Capgras syndrome occurring because of it? Maybe the organic cause leads to feelings of disconnectedness that lead to Capgras syndrome. Maybe it's too tough for people with a brain lesion to update memories when they see a person and the person looks slightly different. Your body is having a strange experience and your brain scrambles for a way to explain it.

Still more doctors and researchers combine the idea of both a physical and a cognitive cause. There's something wrong with the brain, but why and how is Capgras syndrome occurring because of it? Maybe the organic cause leads to feelings of disconnectedness that lead to Capgras syndrome. Maybe it's too tough for people with a brain lesion to update memories when they see a person and the person looks slightly different. Your body is having a strange experience and your brain scrambles for a way to explain it.

Intermetamorphosis

Intermetamorphosis