| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 40| October 12, 2012 | |

|

|

Cover Story

Terrible Tourism To save the forest that protects us from the wrath of nature, we need to respect its secrets and behave responsibly. It is also time we develop guidelines and restrict mass tourism that threatens the vegetation and wildlife of the world's largest mangrove, the Sundarbans. Tamanna Khan

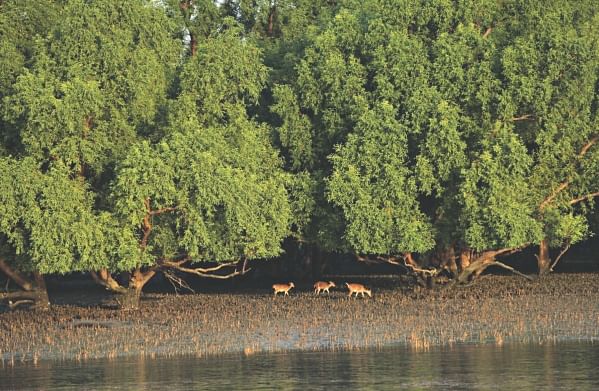

This was my fourth trip to the Sundarbans and yes, not having seen the Royal Bengal Tiger even once in its real home is a disappointment. But I must say, inside the Sundari forest of Herbaria, stuck knee-deep in mud and submerged to the waist in murky water, surrounded by the mesh-like branches of Sundari, Gewa and Passur, a tiger would not have been a welcome sight. In fact, Md Masud Hossain, Executive Director, Bengal Tours, chaffs, “If you want to see tigers go to the zoo.” To my consolation, he adds that he never comes to the forest to see the tigers. Hossain is right. The Sundarbans has much more to offer than just the sighting of wildlife. It is the single largest chunk of productive mangrove forest in the world, with an area of one million hectares, of which 60 percent falls under Bangladesh and the rest in India. Mangroves are plants growing on sheltered coastlines throughout the tropics and the subtropics. Besides the Sundarbans area of India and Bangladesh, mangroves can be found in Indonesia, Brazil, Australia and Nigeria. However, the mangrove forest is scattered in most of these countries and not as nice as the Sundarbans, says Professor Haroun er Rashid, Director, School of Environmental Science and Management, Independent University. “Trees, beaches, creeks and animals all are found here together. It's unique in the way that big animals are in there which is not found in other mangrove areas,” he explains, “The big animals are both predators and prey. You don't see much of the action but then you are not supposed to see the action. People are often curious with wildlife but they must remember that wildlife on its own generally does not reckon with human interference. So most of their action takes place outside of the human gaze.”

That is one reason why you need to be silent and stealthy during your expedition into the forest. One thing is for sure: the birds and animals of the Sundarbans do not belong to the noisy lot. At dawn or dusk, if you take a boat ride through one of the numerous khals (tidal canals) that criss-cross the entire forest, you find that even the birds getting ready for the day or night, communicate in a much milder tone than the city's disappearing bird population.

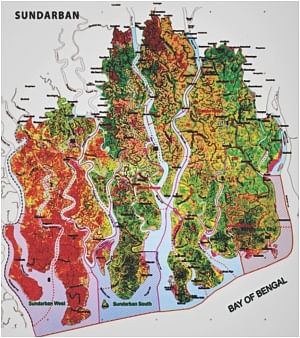

Giving a first-hand example of what happens when mechanical noise intervenes in the jungle, Zahir Uddin Ahmed, Deputy Conservator of Forests, says, “When we toured the jungle today in a boat, the engine was making loud noise and none of us liked it. Because of this noise, we could not see any wildlife. Loud sounds frighten wildlife away. Some species of wildlife migrate to another area leaving its own territory. Due to this, an imbalance may take place as the behaviour of the animal changes as it shifts to a new territory. This is applicable to birds, mammals as well as reptiles.” But how do we keep the noise down when on average two-three hundred tourists visit the forest a day between October and March, which is considered the tourist season for the region? Doing the math, one may doubt the harm that a few hundred tourists can do to a forest spread over a million hectares. The problem, however, arises as tour operators mostly conduct tours, ironically, in world heritage sites. In 1997, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) declared the Sundarbans as its 798th heritage site to protect the unique features of three wildlife sanctuaries. They are located in the east (Katka-Kochikhali), south (Hironpoint) and west (Manderbaria) of the forest covering a total area of 137,900 hectares.

Although all human induced operations such as fishing, crab harvesting, collecting shrimp fry or any non-timber forest produce is prohibited in the wildlife sanctuaries, these three world heritage sites remain major tourist attractions for their rich wildlife. “Last year, the forest department earned Tk 11 million from the two hundred thousand tourists who visited the forest”, says Ahmed. “This is higher than the revenue earned in any past year. But we are worried and concerned about the development of mass tourism in the Sundarbans. We instead want a low impact tourism that will not harm the biodiversity of our forest.” While noise is just one by-product of mass tourism, controlling the behaviour of tourists becomes another challenge. You should not be surprised if one of your fellow travellers shows interest in devouring deer meat, though any kind of hunting is illegal in the Sundarbans. Professor Rashid says, “I believe that certain people go there and catch deer in quite large numbers, which is totally prohibited.” He insists that such activities are not only unconscionable but also disturb the natural equilibrium. He explains that a reduced deer population means a shortage of food for the Royal Bengal Tigers which then has little option left but to turn on man.

Even if poaching can be prevented, sheer physical movement of humans as a result of mass tourism also frightens away the animals, says Rashid. “We are interfering with the growth of trees by pulling shoots, pulling off leaves, etc.” In fact, except for the beaches and the grasslands of the forest, if you opt for trekking in other parts, you may just happen to trample over the breathing roots of the mangroves. Some over-enthusiastic tourists also try to collect fruits and leaves, which is not advisable as the sap of leaves like that of the Goran tree may burn the skin and cause blindness.

Though only guided tours are allowed in the Sundarbans, only a handful of tour operators carry out responsible tourism. At present there is no guideline for conducting tours within the Sundarbans, though all visitors and boats require permission for entering the forest by paying a fee to the Forest Department. Two forest guards must accompany each tour to the forest. But it is not humanly possible for them to monitor every single activity of a tour group which sometimes exceeds 100 visitors. Masud Hossain, says, “The current practice of tourism is not at all acceptable.” He adds, “We do not want to turn the Sundarbans into another Cox's Bazar or the St Martin's Island where the natural beauty has already been damaged due to unabated littering and pollution.” “During the tourist season about 10-15 vessels come and anchor at Katka- Kochikhali area,” he says, noting that Katka-Kochikhali falls under the eastern sanctuary of the world heritage site. The sound of generators accompanied by loud speakers used in many vessels creates irreparable disturbances in the surrounding forest area. Dumping waste and smoking cigarettes in the forest are some of the other irresponsible activities which become impossible to control when large groups visit the jungle.

Irresponsible tourism not only threatens wildlife and vegetation, but becomes fatal for the tourists themselves. Hossain refers to the Katka beach incident of 2004 when 11 students of Khulna University and Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology drowned. He thus stresses the need for guided tours and educating tourists about the dangers and rules of the forest. Only three or four tour companies that conduct regular tours in the Sundarbans abide by certain quality standards. They brief tourists about the forest prior to the tour, provide trained and experienced guides during jungle expeditions along with the Forest Department's armed security guards, ensure that food, drinking water and medical facilities are on board during the voyage and most importantly manage waste in an environmentally friendly way. However, the same cannot be said about all the touring vessels Tthat enter the Sundarbans. Currently, the 15-20 vessels that regularly cruise the Sundarbans are registered with the Forest Department but unregistered vessels are also allowed to conduct seasonal tours in return for a fee. Many of the seasonal tour operators are not even members of any registered tour operator's association, Hossain points out. As a result, they cannot be held responsible for their activities by a governing body. “There must be a criterion for the vessel as well as minimum qualification for the tour operators to conduct tours in the Sundarbans,” insists Hossain. Zahir Uddin Ahmed says that this year they have drafted a guideline for Sundarbans tourism, which details the duties and responsibilities of tourists and tour operators as well as the management responsibility of the Forest Department. The draft also marks routes that the tour vessels must use for entering and leaving the east, west and south zones of the forest. Ahmed says they have also tried to define the number of tourists who can visit the sanctuary at a time. “We have tried to decide on a carrying capacity for each of these sanctuaries and include it in the tour management,” he says. The draft also dictates the maximum number of people an authorised tour vessel may carry, with updated certification of Bangladesh Inland Water Transportation Authority.

Not all the clauses of the draft guidelines are acceptable to Hossain, a representative tour operator. For instance, in Hossain's opinion the maximum number of people a tour vessel can carry should be 50 and not 75, as suggested by the Forest Department. He also opposes the routes fixed by the Forest Department as he thinks that it will add to the fuel cost of the vessel. Lastly, he criticises the Forest Department's refusal to take responsibility for any accidents or damage that may occur during the tour. However, the Deputy Conservator, Ahmed assures that once the draft is approved, amendments can be suggested by the tour operators if required. “The primary need at the moment is to have at least a guideline for managing tourism in the Sundarbans,” he notes.

Both Ahmed and Hossain are strongly against any permanent establishments such as hotels, motels and rest houses within the Sundarbans. In fact, Hossain opines that if the Forest Department permits tourists to stay in their rest houses, as the one in Nilkomol, Hiron Point in the south sanctuary, then private companies will get an opportunity to argue for building similar establishments inside the forests. Hossain suggests developing tourist spots in the periphery of the forest. “Like Karamjal, two more points where day trips can be conducted should be developed.” Karamjal is a wildlife breeding centre reared by the Forest Department, where tourists can see deer, monkeys and crocodiles. It is a half hour cruise from Mongla. “Tourists can stay in the locality but there should not be any night resting facility in the forest,” he emphasises. In Professor Rashid's opinion all sorts of tourism must be prohibited in the sanctuaries and those which are allowed should only be accessible upon special permission for conservation, education and research work. Hossain agrees, adding that only high-end tourism, where eco-friendly and educated tourists willing to pay a premium price, should be allowed inside the sanctuaries. For the general tourists, Hossain suggests visiting other places deep inside the forest but outside the sanctuaries such as Shekhertek, Dubeki and Tin Kona Island. “Tourists can also anchor their boat at night between Haringdanga and Supoti,” he says. In his opinion, developing these areas as tourist spots will stop the traffic in the middle and restrict entry and over night stays in the sanctuaries, as it happens now. He says that these places will give tourists a flavour of the jungle along with the option of trekking and cruising, simultaneously keeping the uniqueness of the three sanctuaries undisturbed and intact. “These places [the ones outside the sanctuaries] are a nearer locality and easier to reach. From here, day trips to the sanctuaries can also be made if needed,” he advocates.

Given today's reality, tourism cannot be totally stopped in the Sundarbans. In fact, sustainable tourism has helped conserve forest and wildlife in many parts of the world. Hasan Rahman, a free-lance researcher of wildlife biology says “tour operators in Nepal play a great role in conservation of tigers and rhinos by providing shelters to the scientists and conservationists, they also invest money to save wildlife for their own sake.” He further adds, “tourists can play a major role as a watchdog, their regular visits to the Sundarbans can make us alert about many adverse situations, and they have great prospects to become whistleblowers. For example if they do not see tigers or other wildlife, as they used to see before, they can make a big noise, and eventually that would force the authority to take measures.” However, to develop such watchdogs, people should be educated about the Sundarbans. According to Professor Rashid, the forest that constitutes half the natural forest and half the reservoir of wild animals in Bangladesh requires much more space in the textbooks of our primary, secondary, college and university education. Rahman also agrees, “If we could introduce the importance of tigers and the Sundarbans in our primary and secondary education, it would help immensely to make them nature lovers, and when they would become tourists they would not behave irresponsibly.”

In 2007 in the wake of Cyclone Sidr, Bangladesh realised the importance of the Sundarbans in a new light. Those who visited the forest weeks after the devastating cyclone, understood how like a sleepless, tireless sentry the vast mangrove protects the coastal regions of the country. “A large human habitation exists near the Sundarbans in Satkhira, Khulna, Bagerhat districts. These communities are dependent on this forest in the sense that the Sundarbans protects these communities from cyclones, tornadoes and high-tides. If due to mass tourism this forest slowly disappears then we cannot save these human inhabitants. For our future generations, we have to develop such a tourism that will protect this forest of ours,” concludes Zahir Uddin Ahmed. Thus if you plan on a visit to the Sundarbans, do not leave your civic sense of duty at home. Go there only if you enjoy the beauty of silence and appreciate the secrets of the forest that has built up over thousands of years. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |