| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 18 | May 04, 2012 | |

|

|

Art

Painting the Streets

Finding art in public places is not a recent phenomenon considering cave men are well known for having painted hunting scenes for others to find. Finding organised street art in Bangladesh, however, is a recent and evolving development. Soraya Auer

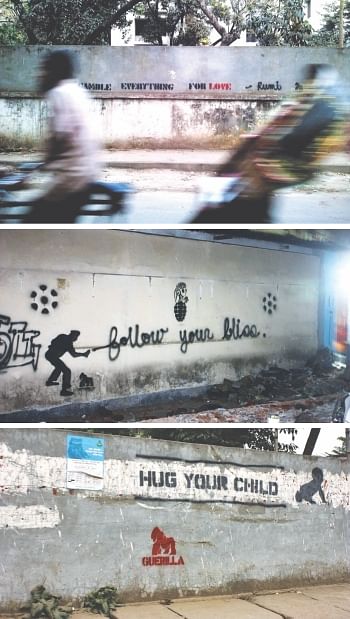

"It's a tiktiki (gecko),” says a puzzled Shazia, a university student, as she drives down a road in Gulshan, Dhaka. She is, however, not referring to a live lizard, but in fact a stencil drawing, spray painted onto a street sign. “What does it mean?” she asks. The meaning is subjective but the small graffiti Shazia points out is actually one of the first attempts of an underground street artist to leave his mark on Bangladesh's capital. “I would smile every time I would pass one of my geckos because it was like a private joke to myself,” says Guerilla, a pseudonymous graffiti artist. “In the beginning, I didn't think anyone actually noticed them,” adds the street artist, who believes in spreading positive and interesting messages to inspire onlookers.

It has been more than a year since Guerilla started his late night work and it is not just pedestrians noticing but a wide online community, as many Bangladeshi street artists are sharing their work through social networks like Facebook. In the past couple of years, individual artists and groups, like Studio Bangi and School of Everything Else (SEE), an open platform for people to share ideas, have been bringing attention to the modern art form known as street art, through chalk drawings, wall paintings and stencil graffiti work. “We see underground artists becoming more active and some are doing a good job,” writes street artist Ehtesham Newaz on Facebook. “But wall art is not something new to Bangladesh. It has been used before to send out messages. During '71, if you see any clippings, you'll notice the writings on the wall. Weren't we trying to mark our territory through wall art?” Newaz also points out that in previous decades many people would ask who Aijuddin was, as a graffiti saying Koshte ache Aijuddin (Aijuddin is unhappy) was written on many Dhaka University walls. The use of Chika (wall art) may not be new to Bangladesh but the nature and purpose of street art has recently evolved thanks to new methods, styles and foreign influences. Twin brothers, Manik and Ratan, and their friend Tabassum Salma, began making stencil graffiti together in 2011. They were motivated by a documentary film, Exit Through the Gift Shop, by Banksy, one of the world's most famous pseudonymous graffiti artists.

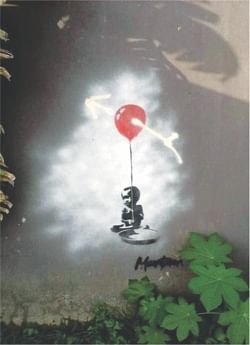

“The way [street artists] visualise social contradictions and their artistic and creative way to protest serious social issues really inspired us,” say Manik and Ratan, who believe the best graffiti work has a concept and message. “Through our stencil work, we want to give a message on some burning issues, like politics, poverty and the Liberation War.” The 26-year-old brothers, who now study animation in Malaysia, continue to make political street art in both Dhaka and Kuala Lumpur. One of Manik and Ratan's pieces near Banani Bridge in Dhaka features the poster child for George Harrison's 1971 Concert for Bangladesh, with an empty plate and a red balloon embodying a piece of happiness. “We tried to say that kids don't need that happiness, they need food on that plate,” explains one of the brothers. Since the picture was stencilled, as often happens with public art, another street artist has come and added his or her mark to the picture. “Someone else added a white arrow trying to burst the balloon,” say the brothers with a smile.

If an artist changed or added to another's piece of art in a gallery, without permission, it would be considered damage and destruction. However, the beauty of street art is that any addition can enhance an image or message – like the white arrow, symbolising how fast and sharply hope and happiness can be ruptured, leaving the child with nothing again. “Street art is organic and not meant to last forever,” believes street artist Guerilla, who works anonymously to separate his art from his personal life. “It's meant to evolve, so people can come up with new ideas and paint over other things. What's great about it is that you don't have to go through the formal channels to have art seen. Street art by definition should be on the streets and not on a canvas in a gallery.” Another aspect of street art's definition, however, is that once art is on the street, it belongs to everyone and no one. Guerilla has experienced firsthand the pain of seeing work painted over a few days after creating it. “It comes with the territory; I'm getting used to it. I'm also learning which walls not to choose, as clean walls are obviously maintained.” However, he adds, “There's never been any reason for street art to be culturally unacceptable.”

There is truth to this belief, as unlike abroad, where officials in cities like London consider street art to be 'crime art', there are no enforced laws for keeping public walls clear of artwork, advertisements or political propaganda. While Dhaka does have a growing network of anonymous and known underground street artists, street art is also making an appearance in Khulna and Sylhet. Many Bangladeshi graffiti artists have also found the public more curious than outraged in recent years. “Street art is easy in this country – even the cops help out,” says Salzar Rahman, a member of the Studio Bangi collective and SEE. “People are surprisingly helpful when they see we're not vandalising. They join in all the time with the painting and even help us out financially to get materials.” “Some places where we've created street art, the owners have since protected the walls from being postered,” says Tamzin Farhan Mogno, also of Studio Bangi and SEE. He explains, “We make street art that we hope people will appreciate and not think of as vandalism. Personally, I started on the streets two years ago because I really hated seeing all those advertisements on the walls, like for cockroaches, and I wanted to change that.”

One of Studio Bangi's treasured efforts is a wall painting at Beauty Boarding House in Old Dhaka. “We had some local boys help us clean up the wall before painting,” recalls Salzar, who, with others at Studio Bangi, co-created the rock band Nemisis's 'Kobe' music video and other animation work. “We took their pictures during the day, and came back at night without them, to add their faces to the wall. When the boys came to see it in the morning, they were really surprised.” SEE has now hosted two street art festivals in Dhaka, and with a growing number of people trying their hand at the modern art form, there is hope that Bangladesh's underground street art scene will surface soon as valued and popular by the whole country. “People are slowly realising they don't have to do street art just at a festival. They are going out day and night as individuals and creating some interesting stuff,” says Salzar. Art was on the streets of Bangladesh well before graffiti found its way onto public walls. Colourful rickshaws, alponas and ornate celebrations have been bringing colour to the streets for decades. Foreign graffiti artists like British Banksy, Italian Blu, and New York-based Faile are influencing young Bangladeshis to stencil more in English, but it is only the early years in this country's street art scene. Street artists are starting to use Bengali to convey messages to the masses and also pushing their creative minds by producing 3D road art and following other inspirations. It is a just a matter of time before the role of street art among Bangladesh's other artistic arenas is consolidated. All the world's a stage, so why shouldn't all the streets be a canvas? To see some more street art, check out Guerilla's website www.guerillabd.co.nr and search for School of Everything Else (SEE) and Studio Bangi on Facebook.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||