| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 44 | November 25, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story The Melody of Chhayanaut Tumi je surer agun lagiye dile more praney Ei agun chhoriye gelo shobkhane (a song by Rabindranath Tagore) The fiery melody that Chhayanaut had kindled in 1961, flared up in 1971, helping to give birth to an independent nation: Bangladesh. Fifty years later, Chhayanaut, a non-partisan cultural organisation, has held on to its spirit of trying to spread the essence of Bengali nationalism through its refined and modest endeavours. Tamanna Khan The rays of sunlight streaming through the large wooden windows of the simple red-brick building that stands without a high-wall boundary is an unsual sight in Dhaka. Like the sun, the Chhayanaut building, designed by architect Bashirul Haque, welcomes all by keeping its door ajar for all who seek the taste of the purity and simplicity of the Bengali identity.

“The objective was to awaken the Bengali cultural identity among Bangladeshis,” says the veteran Dr Sanjida Khatun, President of Chhayanaut and renowned Tagore exponent. “During the Pakistani regime, we felt that, they were trying hard to impose a Pakistani Muslim identity on us. They attempted to erase our Bengali identity. So we thought of forming Chhayanaut,” Dr Khatun relates the history of Chhayanaut's inception.

The realisation came, when the forbearers of Chhayanaut— a small group of progressive minded people of the country comprising of artistes, intellectuals, writers, activists—tried to celebrate Rabindranath Tagore's birth centennial. In their futile attempt of artificial Islamisation, the Pakistan government had at that time tried to shelve Tagore, by terming him as a Hindu poet. But Chhayanaut's warriors armed with musical instruments and love for their Bengali culture successfully staged a month-long celebration all across the country, defying military intimidation. Born initially as an association of artistes and cultural activists, who rendered Bengali songs of refined taste in their original forms, Chhayanaut soon felt the need for more trained artistes. Prominent journalist-activist Waheedul Haque then took the helm. With his and his wife Sanjida Khatun's salary as the initial capital, he visited homes of cultural minded people to collect students. Thus started the journey of Chayanaut music school, on the verandah of Bangla Academy, Dr Khatun's workplace.

The classical ragas that were sung on the first-floor of the Burdwan House still rings in Iffat Ara Dewan's ear, Chhayanaut music school's first-batch student and now a prominent singer of the country. Dewan, known for her immaculate presentation of Rabindrasangeet (Tagore's song), says, “When I started taking singing lessons in 1963, at that pre-Liberation era hardly anyone went to Shantiniketan for training. Most people, I know, went after Liberation — Bannya, Sadi, Papiya. I also had that opportunity but I felt that whatever education and training I received from Chhayanaut was enough. I never felt the need to go anywhere else.”

Forty-eight years later, students still have the same confidence on the lessons imparted by Chhayanaut. Shahnaz Parvin Lovely, student of the folk song department of Chhayanaut opines that not only Tagore's song, any other genre be it Nazrulgeeti (Nazrul's songs) or folk music, this institution teaches student the correct and original tune and the proper way of presenting the song combining melody with rhythm and tempo. Lovely however has one complaint. She has often experienced variation in the tune or words of folk songs, when it is taught by different teachers. However, Anindya Rahman, executive officer of Chhayanaut, explains, “Folk songs have evolved orally. Unlike Rabindrasangeet, no written notes of these songs can be found. There is no way to prove what constitutes the correct music.” Chhayanaut however does not restrict itself to mere teaching of the music. Noted folk singer Nadira Begum, department head of folk song, always briefs her students on the history, origin and background of the song and its composer. “Chhayanaut has given me the opportunity to share the knowledge that I have acquired,” says Begum, daughter of musician composer A K Abdul Aziz. “One can feel the purity, beauty and creativity of music here and delve into it,” she adds citing her reason for joining Chhayanaut. The music school, which was officially inaugurated on the Pahela Baishakh of 1963, now teaches song, dance and instrument playing. The departments for song — Rabindrasangeet, Nazrulgeeti and Folk Song— offer three programmes: music introduction, music initiation, and music entry. Music introduction is a one-year appreciation course open to all. Students have to take an admission test for music initiation, a four-year course for children and two-year course for adults. “We offer the Music Entry course (four-year) only to students who show further interest in learning during the Music initiation course,” says leading Nazrulgeeti singer Khairul Anam Shakil, General Secretary of the executive committee of Chhayanaut. The recent re-structuring of the curriculum has been done to create quality artistes across the country while at the same time offering a taste of music to anyone who wishes so, he adds.

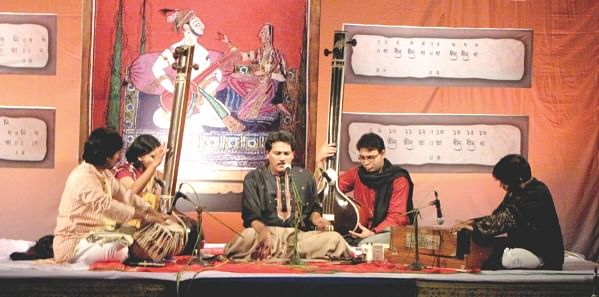

He also dismisses the perception that Nazrulgeeti receives less priority at Chhayanaut. Shakil, also the head of Nazrulgeeti department says that the misconception has risen since Chhayanaut's beginning is associated with Tagore's centennial. Referring to some of the other leading Nazrulgeeti artistes of the country, he says that about 70 percent of them are from Chhayanaut. With regard to the use of the correct tunes for Nazrul's songs, Khairul says that teachers at Chhayanaut are asked to follow the notes published by Nazrul Institute which are based on original records of Kazi Nazrul Islam. "Where documentation is not available, we follow the notes recorded by Jagat Ghatak," he adds. The classical music department of the institution, unlike the other departments, does not offer any time-bound course as students are admitted as apprentices under a music-master. Anup Barua, head of the classical music department, explains, “There is no time limit for us. A student may need ten to twenty years to learn the craft.” Regarding the importance assigned to classical music by the institution, Barua says, “The name Chhayanaut, which is a raga, itself shows how much importance classical music receives. Chhayanaut has always considered classical music as its basis.”

Parag, Tanvir and Sajid, while sipping tea during the break of their rehearsal class, explain why they have chosen to learn classical music at Chhayanaut. "If you practice classical regularly," says Parag, "you will be able to continue to deliver the delicate vocal styling even at an advanced age. People will listen to their songs for a long time. Classical builds up the voice." Unlike many of their generation, the three young classmates, not only appreciate classical music but also approve of Chhayanaut's discipline. They respect the rules regarding the specific type of attire students of Chhayanaut are required to wear. Parag says, “It is said that when you wear white, your heart turns white and when you wear something glittery it feels that way. So attire matters.” The simple cotton sari and panjabi not only upholds the Bengali culture but also eliminates class difference, opines folk song student Lovely. Student of dance classes are however not required to wear sarees. They can choose between white kameez with red or black pajamas and dopatta. Taskin Anha, student of Bharat Nattyam, says, “They teach student very systematically here and I shall receive a certificate after course completion. Exams are held at the end of every year, so that my learning can be assessed.” The dance section, which was started in the 80s, now has three departments — basics for children, Monipuri and Bharat Nattyam. Farhana Ahmed, a Chhayanaut graduate and now a Munipuri dance teacher at the institution, says, “Chhayanaut is not involved in commercial dancing. In many other places, the dancing lesson is aimed at a particular cultural programme. The objective there is mainly to promote oneself or gain popularity. It is not so in Chhayanaut.” She asserts that students are taught to respect and dedicate themselves to the art and its practice in Chhayanaut.

Anha reflects Farhana's claims when she says, “Our dance teacher Sharmila Bandypadhyay had once told us that at Chhayanaut: 'We impart knowledge and education to students in such a way that you will automatically become an artiste'. We will receive exposure through our work; we do not have to seek it.” Although Chhayanaut's half a decade of endeavour has cultivated good Bengali values in the minds of its 50-60,000 students over the years, the 2001 bomb blast at the Pahela Boishakh function at Ramna Batamul, Dhaka, questioned the effect of their effort. Dr Khatun says, “When the bombs went off at Batamul in 2001, we realised that we are not being able to reach the masses. We have not been able to mentor all the people of the country. Only those who come to learn music are getting nurtured. If we want to spread these values to the people of the country then we have to build them up from a young age. As a result we started Nalanda.”

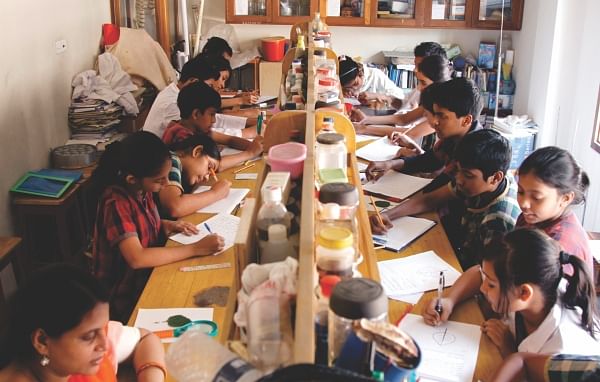

Inaugurated on November 15, 2001, the school started its classes on January 2003 with 16 students and three education-facilitators in Kalabagan, at Nalanda's principal Momena Begum's residence. Nalanda derived its name from a university of the third century CE near the capital of the Magadha kingdom, Pataliputra. “Nalanda is like an extension of their (students) homes. They can come here and open up, follow their heart. We do not teach them anything, in the sense that we work with them, we encourage them, motivate them; we observe and take into consideration their likes and dislikes, so that they can do pursue they like best. We infuse the curiosity of knowledge; indulge them to ask questions without fear.” Giving instances of how students actually get wet in the rain and experience the feeling before writing or reading a poem or a story about rain, Momena Begum explains their teaching method. Interestingly, most parents appreciate these unconventional approaches of Nalanda rather than be concerned. Tajmeri Selina, whose son and daughter studies at Nalanda at class-five and Manjuri (Pre class-1), asserts that her son has overcome his shyness and does not exhibit sibling-rivalry after taking admission at Nalanda from a different school. Since the student teacher ratio is 1:10 for Ankur, Kisholoy and Manjuri (Play, Nursery and Pre-1) and 1:20 for senior classes, the teachers can give more attention to the student's needs. Nalanda's affordable tuition fee which includes tiffin provided by the school, has made the school accessible to many. Yet, in every class one or two students from underprivileged families get the opportunity of learning with joy, without paying tuition. Nalanda tries to maintain the economic class representation in its classes based on government statistics.

Last year, Nalanda's children have appeared at their first public examination with 18 of them obtaining first division marks and one second division. Selina is satisfied with the school's performance and has not sent her son to coaching centres like many parents do. “I have kept a house tutor this year only because my son is a little slow in writing. Nalanda do have extra classes for children who lag behind, but even then giving one-to-one attention is not always possible,” she says. Noor-e-Jannat, another student who will appear at the upcoming public exam, does not receive any extra tuition. “They do not pressurise you to learn anything rather everything is fun to learn at Nalanda. The way they teach math is totally different from the way they teach at other schools. The problems become very easy to comprehend.” One of Nalanda's problems is the shortage of space. Even if the school wants it cannot expand without compromising the quality. As a result they have decided to keep their education endeavour limited to school level. The other problem is training education-facilitators in Nalanda's values because it takes time. “The new education facilitators have to attend and observe the classes of experienced facilitators. They also must be physically active and willing to sing and dance with children. The first part of the interview includes attending the classes for twenty days. After that they take a test which is followed by a 3-6 months probationary period before they are made permanent,” briefs Momena. Since Nalanda alone cannot serve the purpose of spreading Bengali values and cultures among the young minds of Bangladesh, Chhayanaut has started another programme called Shikor in 2009. Aimed at children who are being constantly bombarded with the tackiness of a commercialised and consumerist society, Shikor offers an opportunity to know and explore their cultural roots. Children aged six to thirteen spend Saturday mornings at Chhayanaut building singing, playing, dancing, painting, sculpting — engaging in whichever activities they like, facilitated by Chhayanaut's dedicated volunteers. Shikor children are also taken out on nature walks. One important objective of Shikor is to familiarise the children with Bengali food and culture. Food and fruits from remote corners of Bangladesh are cooked or brought in for the children to enjoy. Chhayanaut in its endeavour has not forgotten the needs of special children. Launched in 2009, 'Surer Jadoo, Ronger Jadoo', provides music and painting lessons on every Thursday to autistic children. Another recent project is 'Bhashar Alap' — a Bengali language training course, where adults are taught the history, sounds, rules of pronunciation and spelling, language delivery and rhythm. The course also includes reading Bengali literature, its context and familiarisation to Sanskrit. Dr Sanjida who sometimes conducts a class says, “There is nothing to make adults aware of the language. Even government officials have told me, 'There are so many courses for English training but none for Bengali. We want to learn these.'”

Along with its educational programmes, Chhayanaut's original venture of presenting refined and tasteful cultural presentations akin to the Bengali tradition goes on through its monthly programmes, classical song and dance festivals and celebration of Rabindranath and Nazrul's anniversary and the national days. It was Chhayanaut that presented Bengalis with the culture of starting their New Year out in the sun with music of hope ringing through their hearts. Chhayanaut proved that the music of the Bengali soul cannot be suppressed beneath military boots or religious fanatic's threats. Chhayanaut continues to play the melody that makes us proud of our Bengali identity.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||||||||||||||||