| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 34 | September 09, 2011 | |

|

|

Art Passion, Penchant and Imagination Fayza Haq

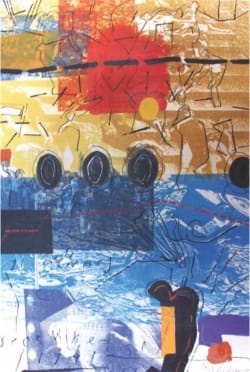

As evening envelopes Dhaka, bright-eyed Rafie Haque – a pet of senior professors of the Arts Institute, like Rokeya Sultana – with his black, curly hair, sparkling eyes and a smiling, buoyant front, speaks to The Star. “My collages, on the World War II, Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, which I exhibited, earlier on at “Jojon”, “Alliance Françoise” and at “Shilpakala Academy” were based on a fellowship of the Japanese government trip to Japan. Here, at a museum, in 1998, in Hiroshima, I witnessed the cruelty and bestiality of mankind. I felt this was similar to the genocide by the Pak army in Bangladesh. What the US bombings did in Japan, Pak armies did in my country, when I was six. Both the attacks were meaningless and cruel. There was no basis for the US forces to drop the bombs in Japan, just as matters were in the attack on the defenceless people of Bangladesh. What the US policy was in Vietnam. Afghanistan etc. were pretty questionable too. Later on, in my visit in 2000, to Fuko Oka Asian Art Museum, during my reside ship, I worked on the same concept. Since my major subject was printmaking, I combined lithograph with painting. I transferred the image on the stone to the paper through a Xerox copy which soaked in gum and then made wet. I did not use acid. This was similar to the “viscosity method” taugh. at France to artists like Kalidas Karmakar, years back. I had learnt this method from a visiting US artist, Karen Kuntz.” When Rafi Haque came back to Dhaka, he played with space in the Piet Mondrian inspired work, for which he won acclaim in Paris. These forms radiate happiness and contentment. These, says Rafie Haque, hark back to his childhood. Kites, at that time, played an important part of his childhood in the countryside, like so many Bangladeshi artists. Asked to speak about his background, which led him to be an artist and not the conventional choice of being banker, lawyer or doctor, Rafie Haque says, his family wanted him to be a doctor, as he had good results in his school life. With good marks in his Matriculation exams, he could finally enter the Dhaka Fine Arts Faculty, on which he had set his heart on. His father ran a publication house, where he came across many illustrated books and magazines, which led him to draw and carve on walls and barks of trees in Kushtia. At times he used pieces of charcoal and bits of broken brick to do his illustrations. He also wrote in his youth, and he even won in nation-wide competitions, as a poem in 1982. He also took part in literary organisations. Asked if he felt that that overseas education was a must for a complete artist; and he was satistisfied by the fairly tight control of the art market by the galleries and art buffs. Rafie says that for a small country like Bangladesh, artists have done fairly well both at home and overseas in a relatively limited period of time. The soul pitch of an artist, in expressing his mind and soul, should be appreciated. Why must truly creative persons sing his canvas for a song? An artist's philosophy and ideals should be given credit. If one' has to cater to the buyers, the artist has philosophy or soul, that he can call his own..

Talking about the contemporary Bangladeshi artists, who live overseas, and come home to share their knowledge, and see their family and friends, Rafie Haque says, taking Monirul Islam in Spain, Shahid Kabir, who also chooses to reside in the sunny home of castanets and flamenco dances, Salim who lives in Manhattan, US, Shahabuddin in France, that they have done a lot to present the country before the eyes of the world. They have participated in various exhibitions overseas. When Monirul Islam came from Spain, says Rafie Haque, he realised that Monirul Islam had strong links with the contemporary artists of his time. Picasso, Tapis, Miro etc. all originated in Spain. “He opened up many new windows on art for every artist from overseas, whoever he may be, brought some thing new for us” says Rafie. Bangladesh not being a highly developed country, students do not get the opportunity to go overseas to widen their outlook easily. To meet and exchange news and views with maestros from overseas is a boon for them. At times it is difficult to get the visa; at others, there are too strong family ties that bind them down and hold them back. The senior artists, based overseas, bring the beauty or culture that they see in Europe and the US. “They bring the rhythm and colours from overseas and they build our drive to improve ourselves, when we are not quite mature, as we are today – with our own experiences in outward. These visiting senior artists inspired us, to work with more passion and imagination. Doing workshops together changed the style and outlook of the younger artists. We were all affected by our visiting teachers,” says Rafie Haque.

Zainul Abedin, SM Sultan, M Kibria are the giants of Bangladeshi art why are the artists who follow their footsteps in the twenty-first century, not that dynamic or remarkable? Have our sense of values and our world changed? We are now all in a big hurry. But exactly where are we heading? To these questions Rafie Haque says, “The world of Zainul Abedin, S.M Sultan, Shaifuddin Ahmed, Shafiuddin and others who were our fathers, was bigger than that of ours. They had enormous commitments. They struggled and made a base for artists that followed them. They could easily have passed their lives in Kolkata, India, where they were established. They were all Kolkata Art College teachers. They came to a new world after 1947 and it took a lot of courage for them to take the chance that they did. “Today there is so much of political unrest around us, and each artist tends to keep himself within himself– rather than disseminating the knowledge to young painters around him” says Rafie. “One notices that after Zainul Abedin, no one really bothered to set up an art college that is respected and trusted by one and all. We are surrounded by a state of unrest and confusion. Peace and tranquillity have apparently abandoned us for good. Socio-economic conditions do not favour the flowering of anything “nouvaue” or remarkable. The existing firebrands can be counted on the fingertips. Hopefully, however, matters will take a different turn.”

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |