| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 09| March 04, 2011 | |

|

|

Musings

Sights and Sounds of History Syed Badrul Ahsan

You tend to think, at times, that Bengalis are fast turning into a nation with a declining sense of history. And that is pretty amazing, considering that history has always been the foundation of societal existence, that through making history at the crossroads of our nationhood we have gone ahead to meet the future. Think of all the disturbing things now being done at Mahasthangarh. Ancient walls dating from Mauryan times are being pulled down in what has been given out as a joint Bangladesh-France excavation project. Perhaps things will turn out all right in the end, but for now we are rather worried. You see, when a wall is pulled down, it is a significant segment of history that is pulled down. You cannot live without history. Which is when you recall all the important spots which once played a critical role in the making of our modern history. The old Ganobhavan, once known as President's House, beside Ramna Park in the nation's capital, ought to have been preserved in the way it was used till 1973, when Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman made use of it as his office. Until he moved to the new Ganobhavan (which was originally meant to serve as a hostel for members of Pakistan's national assembly) in Sher-e-Banglanagar, the Father of the Nation operated as prime minister from the old Ganobhavan. Since 1973, this Ganobhavan has been utilised for multifarious purposes, with no one even suggesting that it be kept as it used to be for reasons of history.

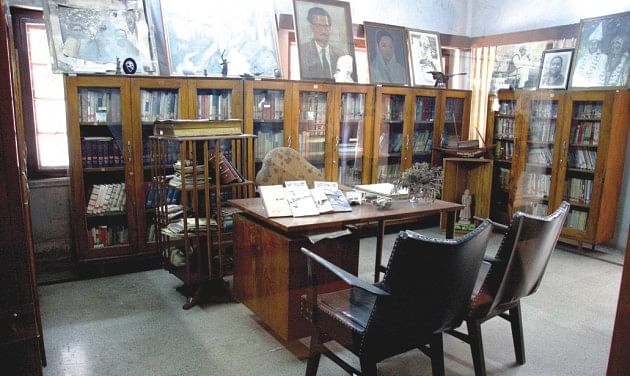

The Ganobhavan was the residence of Vice President Syed Nazrul Islam until the bloody coup d'etat of August 1975. At one point, it was turned into the Foreign Affairs Training Academy. The story of Ganobhavan holds poignance in another way: during the critical political negotiations involving Bangabandhu, Z A Bhutto and Yahya Khan in March 1971, it was the Ganobhavan which served as the focus of attention. General Yahya Khan stayed here and then fled from there on the evening of March 25. Back in 1961, it was this house where Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip stayed, per courtesy of President Ayub Khan, during their visit to East Pakistan. Of course, there are structures and places which remain part of our history. A fundamental one is the Central Shaheed Minar in commemoration of the tragedy of February 1952. Burdwan House, home of the East Bengal chief minister in the 1950s, today houses the Bangla Academy. Bangabandhu's residence on Road 32 Dhanmondi is a museum which speaks of the tragically glorious life of Bangladesh's founder. But there are other sites that ought to have been preserved as well. Tajuddin Ahmed's home in Dhanmondi, symbol of Bengali nationalism in so many ways, does not exist any more. Reports speak of the residence having been given over to real estate developers for reasons we are all too familiar with. Tajuddin Ahmed was one of the greatest men in our history. Should his home have then disappeared in such silence? The good news is that the cell at the Dhaka cantonment where Bangabandhu was imprisoned during the course of the Agartala case has been preserved. And the government has done a most commendable job by transforming the cell in Dhaka Central Jail where the four national leaders – Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, M Mansoor Ali and AHM Quamruzzaman – were murdered by soldiers in November 1975 into a museum. It could have done something similar with the Darbar Hall of erstwhile Bangladesh Rifles, where the beginning of a mutiny in February 2009 ended up taking the lives of 74 people, including 57 army officers. The hall should have been preserved for posterity, as a symbol of the bestiality that all too often has led to the making of unmitigated tragedy in this country. Another hall could have been built to serve the purposes of the renamed force (it is now Border Guard Bangladesh), with the old one, seething with sad memories, being kept intact. The cannon dating back to the period of Mir Jumla, now at Osmany Udyan, ought not to have been removed from where it used to be in Gulistan. Much that is of import in history loses much of its meaning when it is trifled with, in any form. The university residences where Jyotirmoy Guha Thakurta and Gobindra Chandra Dev were shot by the Pakistanis deserve preservation in the interest of national history. The Kali Mandir at the Race Course (Suhrawardy Udyan today) destroyed by the Pakistan occupation army in March 1971 ought to have been rebuilt. It is a pity that it was not. History is always a slow, ponderous march of moving images. It is, at the same time, a series of moments encapsulated in the past, to be remembered in the present, to be commemorated in increasing degrees of intensity in the future. It is a little hut on whose door is a sign telling us that a poet once lived there. It is a narrow alley where young men destined for middle-aged greatness once walked, unaware that each step they took was a new brick laid on the pathway leading to a newer making of history. That hut and this alley must not be lost to time. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |