Cover Story

On the Threshold of Learning

The library culture emerged as a movement in the undivided Bengal in the 19th century. With the historical course changing from a colony to an independent country, the necessity of rich libraries was felt more and more since the advancement of a culture is intertwined with the preservation as well as dissemination of its cultural heritage through its libraries. But how far can the existing government libraries especially those in the city, fulfil the readers' need?

Rifat Munim

Photos: zahedul i khan

The quest for light in human society has mythological precedence. When Zeus deprived the human race from the gift of light, it was the dauntless Prometheus, another god in the Greek myths, who stole fire from the gods and saved the human race from eternal darkness. From there began the audacity of breaking free from the shackles of retrogressive ideas for the sake of truth and progress, even though it has always involved a bumpy ride, requiring the rider to go against the grain. In Banghladesh Aroj Ali Matubbar, who came from a farmer's family in a remote village in Barisal, bore the legacy of Prometheus. He started his journey by sailing a boat everyday for several miles only to get to a library in Barisal and then return home after collecting books. The self-taught iconoclast then became the true renaissance thinker of the country and much like an eighteenth century humanist philosopher he dealt with fundamental philosophical issues with his uncompromising quest for truth. But the price was high, he had to endure brutal diatribes to the point of being ostracised yet did not give up spreading the light in rural Bangladesh. Finally, he ended his journey by establishing a library in his village because he believed that not institutions, whether religious or educational, but a rich library alone could arouse in an individual the quest for light or truth, and the love for humanity from deep within, eradicating superstitions of the dark ages. Although darkness still persists in every corner of the villages and even among the city folk, this torchbearer showed us all how to initiate the fight.

|

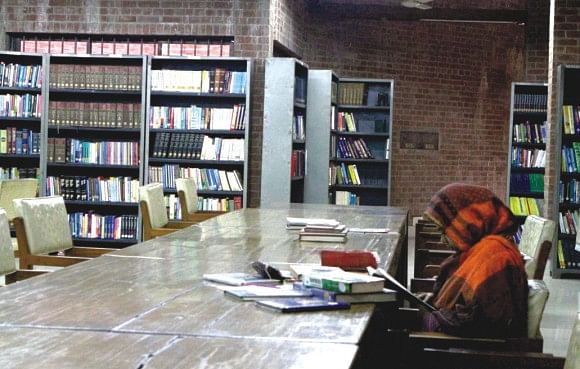

The reading room offering English books

on the second floor at the National Library,

which is rich with old and new titles but

does not see many readers |

The role of libraries in the modern world, needless to say, is pivotal. Not only do they provide readers with the treasure trove of a nation's achievement in literature, science and history, but also ensures people's free access to the world of information, be it politics or science. Hence in order to keep abreast of development and progress in a world dominated by information technology, libraries can be turned into a catalyst to incite people's thirst for knowledge for all the latest developments in science and technology, politics and literature. Obviously for that to happen, libraries have to be modernised as well as digitised. Although enlightened personalities such as Aroj Ali in a small scale and Abdullah Abu Sayeed in a large scale have privately facilitated people's access to libraries, the role of the government in ensuring people's access to libraries and thus their right to information can hardly be overemphasised.

Curiously enough, when one steps into the reading room of the National Library of Bangladesh at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, one is faced with a different picture altogether. Although the three reading rooms see just a handful of readers in the morning, they are almost empty during noontime and afternoon. The sheer dearth of readers begs the question if the library goers have diverted their attention to theatre, films or internet browsing as a result of some invisible social or historical change. However, the somewhat odd location of the library, which is far away from downtown and most of the educational institutes, accounts for why the huge collection of the library remains unknown to most people and unreachable to those who know but cannot make it there for its odd location.

|

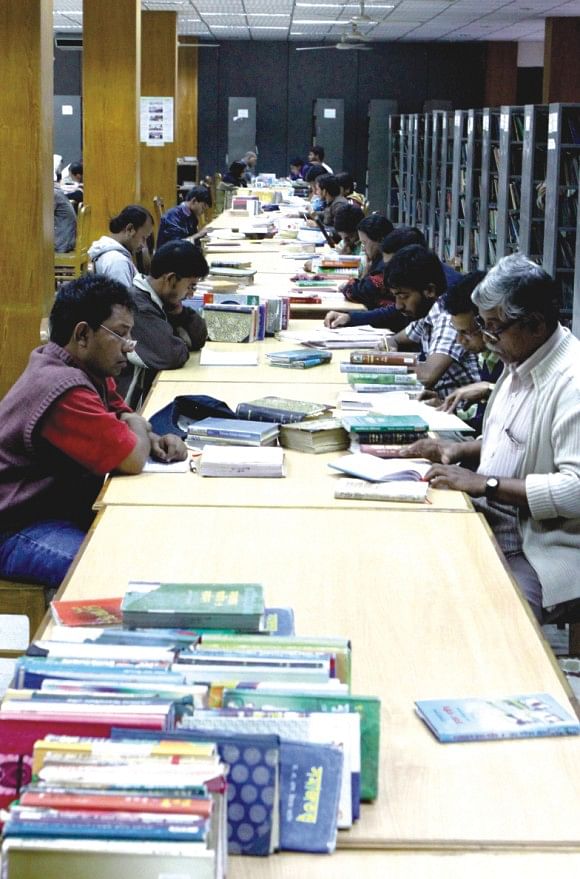

The reading room offering Bengali books on the second floor at the

Central Public Library. |

Farhana Mahfuz, a student of BBA at Bangladesh University, is one of the few readers who visits the library regularly. She says, “The collection of this library is so rich that I cannot help coming here whenever I get a chance. I think readers should know about it.” Shabnur Mahmud Jyoti, a class ten student of the nearby Sher-e-Bangla Nagar Government Boys' High School, also believes that this is the richest library of the country. However, talking about the dearth of readers she refers to an essay 'Boi Pora' (Reading Books) by the litterateur Pramatha Chowdhury and says, “I think that the education system is responsible for this because most students are used to memorising their lessons. But if the education system was creative to make the students rely on proper understanding, then, besides text books, they would consult as many books as possible.”

The National Library of Bangladesh, which operates under the Directorate of the Archives and Libraries under the ministry of cultural affairs, is the legal depository of all new books and other printed materials published in the country under the Copyright Law (modified in 2000 and amended in 2005) of Bangladesh. In addition, it has a large collection of important foreign publications. More importantly, it is also responsible for providing ISBN distribution service to the concerned publishers and individual authors. It also publishes a national bibliography of all the books and indexes all the newspaper articles published every year under the copyright law.

|

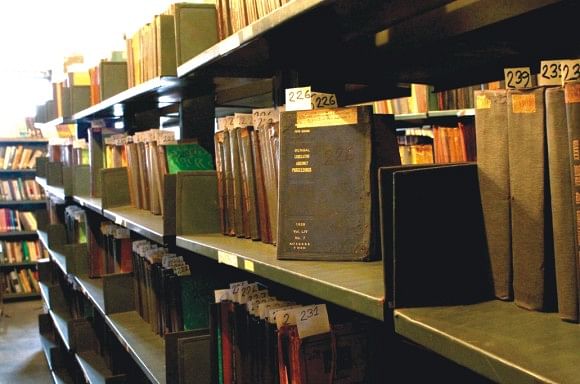

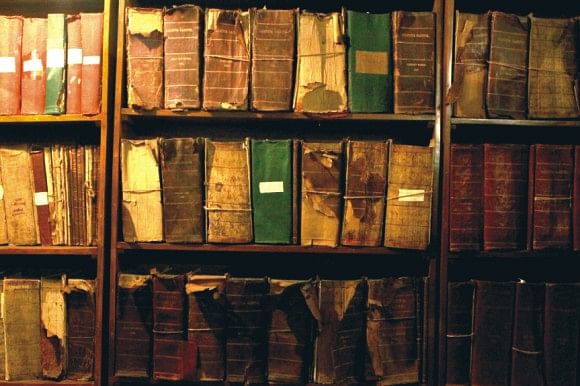

A glimpse at some of the historical documents of the National Library. |

A rough estimate would put the number of books to be no less than five lakhs. Apart from Bengali and English publications in subjects as varied as arts and humanities, physical sciences, social science, life science, medical science and business and commerce, it also has a huge collection of rare manuscripts, books, gazettes, old newspapers and so on. Among its rare collections are the Calcutta Gazettes from the colonial period, the Linguistic Survey of India compiled and edited by GA Grierson, all documents from the East Bengal Secretariat Library and many rare literary and historical manuscripts from the medieval period. Although this huge collection is specially meant for the researchers, general readers also have access to the books and other printed materials.

|

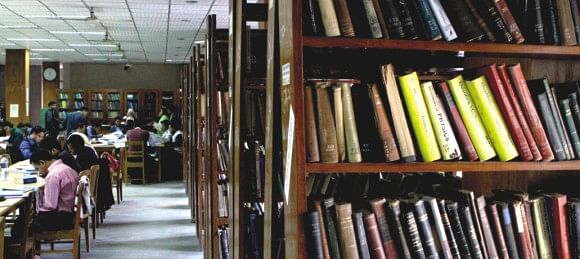

English collections on the third floor at the Central Public Library. |

Md Shahabuddin Khan, deputy director of the National Library, differentiates the role of a national library from a public library. He says, “The National Library is responsible for preserving all printed materials related to national heritage whereas the public library is supposed to attract readers and offer them as many books as possible. So the service we provide mainly lies in long-term preservation of printed materials.”

But long-term preservation especially of rare manuscripts is virtually impossible without digitisation. Tahmina Aktar, the programme officer of the library, says that a project worth ten crore taka is already in the pipeline.

|

Md Nur Alam Talukdar, director, department of public libraries. |

“Digitising the vulnerable manuscripts involves a massive project for which we lack sufficient budget as well as manpower. But we are hopeful as the ministry has promised us a huge budget for this,” she adds. Asked about the microfilm machine which has gone out order for many years and without which records of the vulnerable manuscripts and other materials is impossible, she says, “We have sufficient manpower for the microfilm unit, but the machine is out of order. We have newspapers and journals, which are 150 years old, and we have many valuable maps, which are more than 300-year-old. We feel the necessity as well. As soon as the machine is repaired, we will start working on it.”

Since new books are always replacing the old ones, the readers have to rely on the traditional catalogue system whereby one may have to spend a whole hour or more to find the name of the desired book. Details of an individual book are written on a small paper and kept alphabetically amidst a thousand others. But if the library has a complete database of all the books, readers can just type the name of the book and can get its whereabouts with a press of a button. So without automation quick and proper service seems a far cry.

“We have already completed the database of 56 thousand books. But we need to develop a library management software. Since we have already received a budget of twenty lakh taka for this, we will soon begin to work to that end,” says Farhana Aktar.

Then if the desired book is not on display in the reading room, the librarian is responsible for providing the book upon request in the shortest time possible.

“Some days ago I asked for three travel books. Although I was told not to worry, I was never given the books,” says a despondent Farhana Mahfuz. But Abu Daud, the librarian, says, “We do not get qualified readers, although sometimes we get scholarly researchers. And most often the readers come up with unreasonable requests. However, we try our best to fulfil their needs.”

On conditions of anonymity, one of the staff of the library says that red tape as well as official complications often bar quick implementation of a project.

“When we consider it only as yet another government office, things become complicated. So we should consider it as a people's library and serve the people thereby. And we also need proper patronisation to keep pace with the modern world,” says Shahabuddin.

|

Some of the rare documents at the National Library. |

But the reading rooms at the Central Public Library always see the presence of many readers. Although a good number of the readers come from Dhaka University,which itself has the largest collection of books and journals, the central library attracts many readers everyday. One obvious reason behind this is its convenient location at Shahbagh and its closeness to many educational institutes. The Central Public Library, which has nearly two lakh books and numerous newspapers and journals, attract a variety of readers some of whom are passionate readers, some students while some others use the reading space only to read their own reading material, not anything from the library.

While browsing through the books on the second floor, which is meant only for Bengali publications, it comes out that many of them are not properly arranged. Books, which are supposed to belong to the translation shelf, are wrongly kept in the novel or poetry shelf. Besides this, many books have become so worn out that their titles cannot be read from the cover.

Shuchitra, a Masters student of Sanskrit and Pali at Dhaka University, says that books are poorly arranged, which causes a lot of trouble to the readers.

“Shelf number 83 should provide the translation books. But often I do not get the desired book, which, after searching for a long time, can be found elsewhere. But you cannot be that patient all the time. Then you let the concerned officials know about this, and they will just tell you the shelf number. Then as you tell them the book is not there, they will just show you the catalogues implying that we should look for the book in the catalogue and then find it ourselves,” she says.

Hasina Aktar, a student of Bengali Literature at Eden College, says, “What strikes me most is the scarcity of good books. We do not get as many good books as we need.”

Shuchitra reinforces Aktar's statement when she says, “We always hear that new books are bought. But what we find is books, which were published decades ago. Where do all the books go? What really hurts me is the fact that many of the new books very obviously serve the purpose of the government. For example, if you look at the history shelf, you will find only a few books dealing with facts whereas most others are politically motivated.”

However, Aktar raises another point and says that some of the readers intentionally put a book in the wrong shelf so that others cannot find it. “It mostly happens when there are fewer copies of an important book,” she says.

Md Nur Alam Talukder, the director of the department of public libraries, says that all the library shelves are open which is a major problem.

“After reading, readers are supposed to put the books on the table. But many of them do not pay any heed to that. It creates some mismanagement. That's why we're now thinking of closed shelves.” Asked about strong monitoring of the officials, he says, “We have told them several times to monitor strongly if anybody breaks the rule. But you have to understand that most of the staff consider their work just as a job. They do not love the library. That is another problem. Still, we are trying to make our staff more efficient and responsible to their job. But in many cases, the readers are not co-operative. So they also have to be responsible for certain things.”

According to the director, last year, books worth about one and a half crore taka were bought while this year the budget will increase to about two crore.

“There is a committee comprising pedagogues, eminent writers and government officials. The committee prepares the list taking recommendations from publishers and many other concerned quarters. So the library authorities have little chance to influence the list of the books to be bought.”

Nur Alam Talukdar is against an e-library since copyright materials cannot be digitised. But he is keen on modernising the facilities and services. As part of the modernisation project, database of a huge number of books bought last year has been uploaded in its website.

A single public library is hardly adequate for a city of 13 million. According to Unesco, there should be a library within each square kilometre, informs Md Zillur Rahman, the deputy director of the department of public libraries. Although there are divisional and district public libraries, they can in no way fulfil the readers' need. May be that was why intellectuals like Abdullah Abu Sayeed established the Bishysahitya Kendra. But even the Kendra's libraries are not enough to reach all readers all over the country.

To address this, the central library in association with the DC and UNOs of Sherpur district have taken a project of building up private libraries in the 52 union parishads of the district.

“We are now observing this model. If it succeeds, we will expand our programme. Everyone should come forward and work to build up a library in his village. Many of us do not even know that the National Book Centre, a government organisation, allocates a grant for those interested in private libraries. The grant is first advertised and then distributed among those who apply,” says Nur Alam Talukdar.

Not everyone is as courageous as Aroj Ali Matubbar. But if we really want to make an enlightened Bangladesh may be the first step should be to join hands and build a library in our village or neighbourhood to continue the legacy of Matubbar.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |