| Book Review

The Dutiful Diplomat's Wife

RODRIC BRAITHWAITE

|

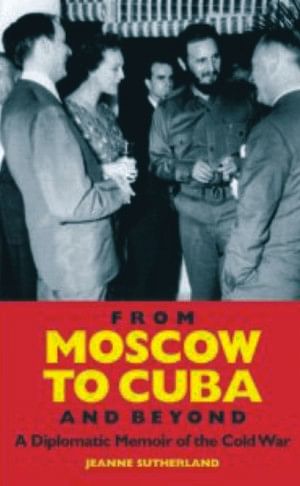

From Moscow to Cuba and Beyond: A Diplomatic Memoir of the Cold War

by Jeanne Sutherland Radcliffe Press; pp336; $44 |

Jeanne Nutt and Iain Sutherland began their careers as professional diplomats in Moscow when Stalin was still alive. Although both had studied the language, literature and history they arrived in Moscow separately. Three decades later they would leave the city together, after three gerontocrats had died in a row and just as things were about to change forever with Gorbachev's perestroika.

By then, Jeanne's career was long over. When she and Iain had married in 1955, she had been obliged, under rules not finally abolished until 1972, to resign. From then on her fate had been to pack and follow her husband wherever his career took him. Luckily for him, for her, and for us, she continued to take a lively and intelligent interest in the people and the politics of the places where she and her husband lived, and where they witnessed some of the turning points of the cold war.

In this book she also gives the flavour of the sometimes bizarre life diplomats led in those distant days. She tells the story through letters she and Iain wrote home, stitched together on a thread of political and personal commentary, and interspersed with the odd letter from a third party.

The Sutherlands served in Cuba, Washington, Yugoslavia, Indonesia and Athens, where Iain was ambassador, but the burden of the book is their three tours of duty in Russia which they were so well placed by training and inclination to understand. The highlight of their first stint in Moscow was the death of Stalin in March 1953. That morning Iain's maid arrived in his apartment shattered by grief. She made him an inedible breakfast, broke down in tears, and fled. The old woman who guarded his front door was sobbing into her shawl. The following day the ambassador, the splendidly named Sir Alvary Gascoigne, went with his staff to pay their respects to Stalin as he lay in state in Moscow's Hall of Columns. The ambassador insisted that all should wear top hats, wholly unsuitable headgear when the thermometer stood at -20C, and the diplomats were ushered past the coffin so fast that one of them missed Stalin altogether.

In those days, diplomats were prevented from any real human contact with ordinary Russians by the Soviet security services and by their own regulations. Most of the Soviet Union was closed to foreigners; some parts were closed even to Soviet citizens. But if you travelled in the bits that remained open you could see many things whose significance escaped the secret policemen. Even better, though people in Moscow were unwilling to talk to you, in the provinces they sometimes felt they could safely open up to a passing traveller whom they knew they would not meet again.

Travel in the Soviet Union was an arduous business of surly and uncooperative officials, inadequate or nonexistent hotels, and missed aeroplanes and trains. Jeanne travelled from Moscow to the Caucasus in 1953 with four colleagues in a cramped car with an inadequate heater, along barely passable roads almost entirely lacking in petrol stations. But travel was a welcome change from the incestuous and largely futile round of entertainment with which the diplomats in Moscow whiled away their time. Even under Stalin, Russia was less mysterious and less impenetrable than it seemed.

So foreigners who travelled and spoke the language gained insights denied to the armchair Kremlinologists who pontificated in their ministries, agencies and thinktanks, 1,000 miles away and more. They could see, as the Kremlinologists usually did not, that the Soviet Union was a superpower with feet of clay.

Tragically Iain did not live to enjoy the freedom from official restraint which retirement brings with it: he died in 1986, only a year after he had left Moscow. Jeanne's book is, among other things, a tribute to his memory.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |