| Profile

A Dancing Sensation

Anika Hossain

“I call my language of movement a confusion, not a fusion,” smiles Akram Khan, the British-Bengali maestro, as he talks about his thriving career in contemporary dance, which has created a sensation worldwide.

Akram Khan has taken Bangladeshi dance, which is predominated by classical forms of the subcontinent, along with traits of folk, tribal and Middle-Eastern qualities and Kathak, which originates from India and molded them into something unique that speaks its own language.

Born in London, in1974 to a Bangladeshi couple, Akram Khan was introduced to Bengali folk dance at a very young age. “My mother kind of forced me into it. Both my parents spoke to me in Bengali all the time. They knew I would learn English in school and they didn’t want me to lose touch with my Bangladeshi roots. At the time I was upset but I’m grateful now because had they not done that, I wouldn’t be able to speak Bengali fluently,” says Khan as he recalls his first few years of dancing, “I did a lot of folk dance to Rabindra Sangeet, my main party solo was Amar Shona Horin Chai.”

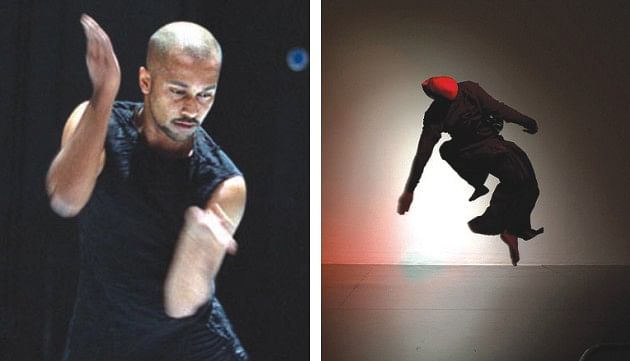

Photo: L-R- theartsdesk.com and allgigs.com

When he was seven years old, Khan’s mother decided to put him under the tutelage of Sri Pratap Pawar, in London, to be trained in Kathak. After a decade of learning this rigid and demanding discipline, Khan’s talent began to emerge and blossom. As a teenager, he performed on stage with celebrated artists like Ravi Shankar in Kipling’s “Jungle Book,” and Peter Brook’s adaptation of the “Mahabharatha.” While the members of his community treated his dancing as a hobby and put pressure on him to study the law, Khan was dealing with a dilemma of a different kind.

“I was a bit frustrated doing Kathak at that time. I was learning a tradition that was somehow mine but didn’t belong to me. I loved it, but I wanted to find what I wanted to do, what I wanted to say,” shares Khan, “there was a time period when I saw the Thriller and fell in love with Micheal Jackson. That was an eye opener for me, that there were bigger things out there than just traditional dance, a whole new world. I began to dream as most children do.”

His inner turmoil finally ended when Khan came across something which helped him make his decision about his future. “I knew I didn’t want to be a lawyer or an accountant like my father. Then one day I came across a quote from Rabindranath Tagore which said ‘In order for art to survive it has to transform with time, and you have to always challenge tradition,’ and I thought if this bearded old man can say this and believe this, it gives me the license to do exactly that. So that’s when I decided to leave and go to university to study contemporary dance.”

In 1994, Khan enrolled in De Montfort University in Leicester to study for BA (Hons) in Performing Arts (Dance). After two years of learning ballet and other modern styles, he transferred to the Northern School of Contemporary Dance in Leeds. “My body became very confused as it tried to adapt to this new way of dancing, that’s why I call my dance confusion. My body decided to combine to two styles by default. Everything happened by default. In Bangladesh, I feel there is a huge gap, between high caliber intellectuals and the majority of Bangladesh, which is really the simple people, the labourers. There seems to be nothing in between. The labourers are people who use their hands, they are very creative and very powerful people and they are the workforce. This extremity is interesting for me. The people who are labourers trust their bodies more and trust the seasons more and nature more and the intellectuals manipulate seasons more or imagine seasons more and don’t really feel the seasons. So in a way I would belong more with the work force, in terms of how I work and feel.”

|

Akram Khan |

Khan graduated with the highest marks ever received for a performance arts degree and he added ballet, release-based techniques, contact improvisation, physical theatre and other contemporary styles to his knowledge and experience of dance. As Khan merged traditional styles with modern techniques, word spread about the creation of a new form of dance and it was named “contemporary Kathak.” William Forsythe and Pina Bausch, the glory of the dance world, named him the future of modern dance. Soon after, in 2000, Khan formed his own company and christened it the Akram Khan Dance Company. A year later, he was given the title of the “Best Young British Dancer.” In the years that followed, his career reached new heights with every remarkable, spine tingling performance.

After several years of working with internationally famous personalities, Khan decided to reconnect with his cultural roots by choreographing a solo theatre performance based on life in Bangladesh. “I’m doing a piece by default about Bangladesh but its not really about Bangladesh its about me and about my experience of wanting to root myself somewhere. I’ve always tried to avoid Bangladesh in my work, because I feel angry at Bangladesh because I think Bangladesh has a lot of problems and I have a lot of problems with Bangladesh. If a talent like Tagore’s was not recognised by the west, he would never be recognised in Bangladesh. I’m not saying I’m Tagore, but in a small way, however small I am, I was never really recognised by the Bangladeshi community I grew up in. I haven’t been to Bangladesh enough to know how they feel about me here, but my community never appreciated what I do. They thought dance was my day job and it wasn’t until I was representing Britian on an international level as a British dancer that they started to look at what I do differently and that’s why I’m angry,” shares Khan.

“There’s a lot of pressure on boys who dance. Dance is a part of our culture but not our religion and that raised some issues about my choice of career. Also male dancers are stereotyped as gay or feminine and there are a lot of gay male dancers so I see where this notion comes from but I’m not. What I find really beautiful is that male dancers can be masculine and feminine just like female dancers can be feminine and masculine. It doesn’t mean they are lesbians or gays. Anyway the issue is they didn’t take me seriously and that’s why I have so much anger towards my childhood,” he shares.

Khan also believes that dancers in Bangladesh don’t have much of a scope to succeed. “There’s no support for dance and to be honest with you the only people I know in the dancing profession here are Shibli and Nipa who are dictators here. I haven’t seen anybody good in the last ten years which is frightening for the health of Bangladesh in terms of dance. I know them I think they’re very nice people what I have a problem with is where are all the rest of the dancers? And for dance that’s a big problem. It’s a shame.”

|

Photo: Amirul Rajiv |

For his current project, which is still under construction, Khan has chosen to work with Chinese visual designer, the Oscar winning Tim Yip who worked in the film ‘Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon,’ the award winning lighting designer Michael Hulls, composer Jocelyn Pook and Kathika Nair, who will be his co-writer.

“I’m not sure what the piece will be about. What triggered it off is, I wanted to do something with water. I thought of the river, as it transforms from the Ganges to the Brahmaputra to the Jamuna. I find it fascinating that it starts off as a female river and at one point becomes male and then becomes female again. I like the concept that rivers can speak to fishermen. I also like that the river originates from India and then it gradually change as it flows into Bangladesh. I feel like when the river is in India it’s speaking in Hindi and when it comes to Bangladesh its still speaking Hindi but its slowly transforming to eventually speak in Bengali. The writer I’m working with Kathika Nair came up with the idea of working with rivers as one of the characters,” explains Khan.

“There will be five or six characters in this piece, and one them will be Noor Hossain. What I like about his character is that he was a nobody, he was just out there with a group and he was the first to be shot, again by default and he became a martyr. I like when things happen by accident or by chance. Another character I want to involve is a fisherman who talks to the river. I will also be playing myself. It will be a solo dance theatre piece and a lot of the texts will be in Bengali, some will be in Urdu and some will be in Hindi, there will be six or seven voices speaking with me and to me,” says the enthusiastic artist, as he explores his different ideas.

“The idea of the languages was inspired by the three identities my parents held in their lifetime. They were Indian and then Pakistani and eventually Bangladeshi and I find that fascinating. There are many things I am exploring with the team that I have invited to Bangladesh.”

Khan and his team have done some research on their visit to Bangladesh this time. They have explored and tried to understand the way of life here. “We have done too much and at the same time not enough,” he states. They watched a play about Lalon, they visited fishing villages in Jessore and Khulna and spent time with the inhabitants, they also went to Shodorghat and were very moved by what they saw there. “We spent hours with the kids there and I felt all these rhythms and beats around me, the sound of hammering as they hit the boats. I’m sure it’s torture for them to hear the same sounds over and over again but for me it was magical,” says Khan. The team also went to a lecture about Bangladesh by Shahidul Alam, a press conference about the Tagore Festival at the British Council and several weaving markets during their stay here, they also watched the movie ‘Runway’ by Tareq Masud as a part of their research.

”When I came here this time I didn’t get Bangladesh for the first time in my life. I didn’t understand Bangladesh. I was trying to understand the country but I approached it wrong I should try to understand the people. If you understand the people you understand the country and that’s what I am trying to do,” shares Khan.

Akram Khan’s new project, which he has named ‘Desh’ will premier in London in October 2011. The project will tour Rome, Dresden, Amsterdam, Luxembourg, Lyon, Paris, Hong Kong, Singapore, New York as well as many other major cities. Khan thinks it will be a shame if he does not bring the production to Bangladesh. For a country that does not have too many international celebrities to boast about, Akram Khan is truly a source of inspiration and pride, and deserves our recognition and appreciation for his tremendous talent.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

|