|

Musings

Quetta... as memory, as metaphor

Syed Badrul Ahsan

In a very big way, Quetta has always been home for me. It matters little that I left it in July 1971. It is of small consequence that the last time I walked its streets was in January 1996. There is Quetta in the memory, the little garrison town I grew up in, the mountain-circumscribed spaces where my most cherished ideas of life took shape. Quetta has never been a city, though in my adolescence it appeared to be a hulk of an urban symbol. Its streets and its lanes were to me some of the biggest in the world. Its summers were blistering, with flies coming from nowhere to settle on the food, on the furniture, indeed on everything that you had at home. And then came winter, the most forbiddingly beautiful in terms of the cold it sent through your very being. In the stoves, the coal burned, showing you patterns in the fiery brilliance. The snow was plainly ethereal and the howling winds that accompanied it gave Quetta a special place in your soul. Something of a fairy tale quality was always there about it. The crimson fall of sunlight against the silent, so distant and yet so near Koh-i-Murdar (or dead mountains) spoke to the boy in me of long ago legends and tales of heroism. In winter, the freezing clouds, almost menacing in appearance, concealed the peaks of those mountains in their terrible grip. I watched from my rooftop, fascinated.

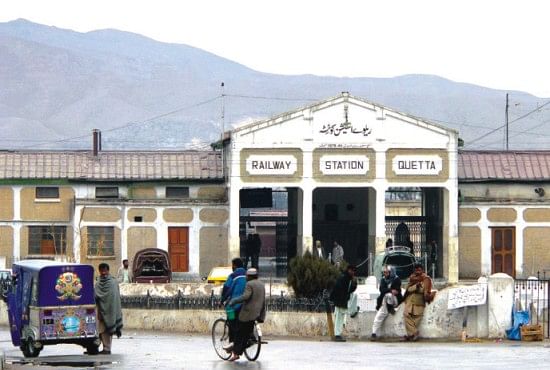

Quetta remains a symbolism for fairy tales and legends for me. In my fifties, it is yet the charming little town where apples weighed down the orchards on Sariab Road. My siblings and I wandered through those orchards, wondering how so many apples could shine so brilliantly, one outshining another. Those orchards were our world. They were too pure to be touched by human hands, until the hands of the Pathan who took care of them reached up and plucked a whole bagful of apples for us to carry home. There are the streets I remember, the little library on Prince Road where I biked down every morning during my winter vacations to borrow comics to read at home. There were all sorts of comics there, classics illustrated and classics illustrated junior and all those Archie-Veronica-Betty-Jughead stories. Goofy and Mickey Mouse and The Beagle Boys are characters I have associated with Quetta. These comics I borrowed from that library. There were others my father bought for me, at the shop called Gosha-e-Adab on Jinnah Road and at the railway station every time we said farewell to him as he boarded the Bolan Mail for Karachi, from where he would travel to Dhaka on tour.

In Quetta, it was an enlightening world of movies that I was brought in touch with. We began with Summer Holiday, proceeding to the comedy “How To Get Married” and on to the Fantomas series and Peter O' Toole's “Night of the Generals”. We watched them all, per courtesy of our school programme to link us to good movies as a way of understanding what aesthetics was all about, at the Regal cinema hall. I searched for that hall when I went revisiting all my old haunts twenty five years after I had left them. Everything was in place. Regal Cinema was the exception. It had been demolished to make way for a shopping complex. Nothing can be more wrenching than the disappearance of things that shaped your sense of understanding in your state of innocence. Regal Cinema remains in the memory. In broad measure, Quetta has always taken up a very large swathe of my memory. It was at Quetta radio station, aged fifteen, that I turned up for an audition in singing. I sang a popular number of the time. The men in the studio asked me to come again. Somehow I did not. Did I miss out on being an artiste?

That question will always hang in the air. And so will another. What if I had stayed on in Quetta and wooed Nighat Farzana in all earnestness? My earliest poetry extolled the dreamy eyes in her and the long tresses whose perfume wafted all the way across the street to me. She smiled prettily. In the dark twilights of winter, she stood at her window, in a state of shy expectation, waiting for me to cycle up and down her street for a glimpse of her beauty. Quetta, then, gave me my earliest lessons on the beauty of women. There were the Pathan women, the Punjabi women, the Parsi women. And there was Gulnar Kapadia, forever pitted against me in inter-school debate. There is the image of Arifa, the light from the overhead bulb falling on her on an autumn evening as she asked me if she could borrow some water from our tap. I mumbled a yes, thrilled to the core of my bones.

Quetta taught me how to appreciate the ageless beauty of mountains and the gleaming timelessness of the streams that flow through them. In Quetta my teachers spoke to me of Julius Caesar and David Copperfield and Barchester Towers, opening up the wide expanses of English literature that I have continued to explore. In Quetta, I came to know of Mirza Ghalib and Kishan Chander. And I devoured the Urdu novels of Razia Butt through the quiet summer nights. On a soft summer evening in Quetta, Bangabandhu pinched my cheeks, a memory that I have kept safe in the treasure box of nostalgia. My respect for him shot up to a state of reverence. It has stayed that way.

When Quetta is humiliated by men out to kill other men, when bombs explode on the streets that once were mine, the soul in me goes into exile. It wanders among the cacti beside the mountains, there where a small stream flows, has flowed since the beginning of time. In the gurgle of that stream it is the journey of men to the moon that I remember. When the moon shines on my ageing world today, it is the light it casts on the Koh-i-Murdar that I think of. It is my baby brother crawling happily toward a grasshopper on a moon-cast field of flowers I recall.

Quetta is a metaphor for what has been, for what will not be again.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |