| Tribute

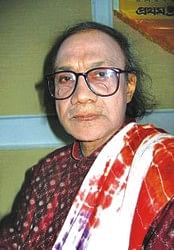

My friend Mannan

Abdus Selim

With total indifference when I took up my first government assignment in Sylhet Murari Chand College as Lecturer back in 1969, after I had resigned (with much tactics though) from the then Ayub Cadet College, Sardah because of its demanding regimentation, I was very apprehensive if I would be able to stick to the job landing in a completely unknown and friendless place. It was then I met Mannan -- Abdul Manna Syed who was teaching at the same college. But Mannan was reserved and taciturn, and did not open up so easily -- the quality perhaps he bore deep within him until his last days.

|

| Abdul Mannan Syed |

I knew his name through the collection of his short stories Shattyer Moto Badmash, which was banned by the then Pakistan government under the Obscenity Act. Though I had not read any of his short stories before I met him, I was aware of the banning of the book through newspapers. The incident reminded me of DH Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover.

My first meeting with Mannan was brief yet meaningful because we had common grounds of literary values and principles, and that led us to meet frequently. During one such meeting, the proposal came from Mannan to jointly edit a little magazine by the name Shilpokala. At that time the only little magazine that was tremendously admired by the would-be young writers and poets was Kanthaswar edited by Abdullah Abu Sayeed. It had profound impact on the young literati of the time and Mannan was a regular contributor to the magazine.

Mannan's format plan for Shilpokala was different from Kanthaswar. He proposed to publish articles on all the branches of art including cinema in the little magazine. But we departed from this principle by publishing a poetry supplement in the fifth issue. Deep within, Mannan was essentially a poet and I told him so when he composed his “Raatri” and with an eerie excitement he read out the poem to me the next day in a restaurant near his Green Road residence in 1984.

Frankly, I was flabbergasted at his proposal, for the only credential that I had as a writer until then was publication of a few stray essays and short stories in the literary sections of some English and Bangla dailies. But he was insistent, and it was planned that the first issue would be published during the summer vacation when we both would be in Dhaka arranging publication cost from personal contributions.

Shilpokala came out in 1970. I wrote an essay inspired by Mannan on literature and obscenity questioning the legitimacy of banning a literary work on the ground of indecency, sex, homosexuality, lesbianism, masochism, etc., for there was no such thing like obscene literature. Obviously it was written keeping Mannan's banned book in mind.

A total of eight issues of Shilpokala came out between 1970 and 1973 covering a wide range of topics on literature, painting, cinema, drama, music, sculpture, and architecture. Two major incidents during the period -- liberation war and death of one of our financial sponsors killed by the Pakistan army -- resulted irregularity in the publication of the magazine and our editorial meetings. Like all conscious patriotic Bengalis we also in our own ways got involved in the liberation struggle being separated from our friends and near ones. But Mannan and I got to know each other better than before, especially when we both were transferred from Sylhet MC College to Dhaka Jagannath College at that time.

Mannan was my mentor in the Bangladesh literary as well as art and cultural world. I came to know all the poets of the 60s personally through him. He introduced me to Mohammad Khasru, a pioneer in the film society movement in Bangladesh which later led me to the world of cinema and drama. Jagannath College at that time was the hub of literary personalities. I got acquainted with Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Shawkat Ali, Shahidur Rahman, Selim Sarwar and many others who were teaching there. Meanwhile I also met legendary Abdullah Abu Sayeed and started writing essays and short stories in Kanthaswar. Immediately I stepped into a new world and fell in love with it.

|

| Kazi Nazrul Islam |

Mannan taught me proof reading, Bangla spelling, Bangla rhyming and metrical patterns and editing. Two of his ideal editors were Sikandar Abu Zafar and Abdullah Abu Sayeed. We had endless discussions on Surrealism, Dadaism, Impressionism, Cubism, Fobism, modernism, postmodernism, stream of consciousness, deconstruction including Communism and Capitalism on different occasions. He loved to be called a surrealist writer and in fact he was one. Among all my acquaintances I found him a tremendously well-read person possessing wonderful ability to assimilate and internalise all the aesthetic constituents of world literature, art and culture. His Matal Manchitro (1970) bears the evidence of that understanding. He for the first time told me to try my hand at translation, which made me render many of his poems including poems of some other poets of the 60s into English and publish an anthology called Selected Poems from Bangladesh in 1985. Only last year I translated one of his short stories selected by him -- his second by me -- into English.

In 1976 I left for England for higher studies on a British Council scholarship and our friendship and activities suffered a gap. When I returned in 1977 we once again planned to publish another little magazine by the name Charitrya. In fact, it was innate in Mannan's character to shift from one idea to another within a short span of time.

We published only four issues of Charitrya and in this little magazine Mannan's most significant research work Shudhatama Kabi germinated. It did not take complete shape until we went to Kolkata in 1978 when we both did a lot of research work on Jibonananda Das. We met a number of poets, writers, intellectuals and academicians of different universities, especially of Jadavpur University. We had several long sessions with Jibonanand's brother Ashokananda and the poet's daughter. Together we also spent hours in the Anandabazar and The Statesman offices, and National Library reading and compiling information on the poet from a pile of old stained papers. We both were welcomed warmly by two renowned teachers of Jadavpur University Comparative Literature department: Dr Noresh Guha and Dr Devipada Bhattacharya who arranged a seminar on Jibonananda Das in the department. Mannan was the keynote speaker, though I was also asked to say a few words on my translation works. In the seminar, Mannan, for the first time spoke about Jibonananda's masochistic tendency. He drew a parallel between Jibonananda's personal life and the protagonist of his novel Mallyaban. But young lecturers doubted his hypothesis and he had to answer many difficult questions. After all these years we know Jibonananda did have a masochistic psychology. No doubt Mannan established himself as a tireless researcher. The other mentionable, if not remarkable, literary work that resulted from our Kolkata visit was his novel Kolkata -- the two protagonists of the fiction being Mannan and myself.

Mannan, in his early life was a loner. This can be easily understood from his first two anthologies of poems Janmandho Kobita Guchcha (1967) and Jotchna-Rouddrer Chikitsha (1969). His thought, similes, symbols, parallelism, and most of all his language were terribly alienated. Though with time he changed, he was never a crowd pleaser. He maintained, “In this ever-changing life, understanding, feelings and experience, inquisitiveness, investigation and realisation constantly shape, reshape, expand, and move forward.” This ever-moving forward was Mannan's inherent character.

Many people misunderstand Mannan as an introvert and a fundamentalist. Mannan was perhaps the only poet, researcher and writer of his age who wrote profusely about his contemporaries. How could an introvert comprehend the minds of his contemporaries unless his own mind was open inwardly? As for religion, Mannan consciously said, “I am a Bengali and a Muslim. It is not possible for me to replace one with the other. As a Bengali Muslim I inherit within me a complex tradition.” In spite of this mindset he always thought Tagore to be the Kabi Guru and many a times mentioned to me Jibonananda should have been the right choice for being our national poet. But he was also an avid worshipper of Kazi Nazrul Islam. Perhaps that is why he once engaged in practising painting like Tagore did, did remarkable research works on Jibonananda Das and Kazi Nazrul Islam, and once even acted in a teleplay as Nazrul did in movies. In fact, I found in Mannan a more profound literary and cultural mind than I do in many so-called progressive intellectuals. Many people misunderstand Mannan as an introvert and a fundamentalist. Mannan was perhaps the only poet, researcher and writer of his age who wrote profusely about his contemporaries. How could an introvert comprehend the minds of his contemporaries unless his own mind was open inwardly? As for religion, Mannan consciously said, “I am a Bengali and a Muslim. It is not possible for me to replace one with the other. As a Bengali Muslim I inherit within me a complex tradition.” In spite of this mindset he always thought Tagore to be the Kabi Guru and many a times mentioned to me Jibonananda should have been the right choice for being our national poet. But he was also an avid worshipper of Kazi Nazrul Islam. Perhaps that is why he once engaged in practising painting like Tagore did, did remarkable research works on Jibonananda Das and Kazi Nazrul Islam, and once even acted in a teleplay as Nazrul did in movies. In fact, I found in Mannan a more profound literary and cultural mind than I do in many so-called progressive intellectuals.

After being separated for a long time we spent three years together once again when he was working as Scholar in Resident between 2005 and 2008 at North South University. Although we traversed a long way away from each other, the rapport was never missing, for when we sat together for adda we lost our count of time and drifted on and on. My friend Mannan is no more and I cannot say now as we did during the 70s: But [we] have promises to keep,/And miles to go before [we] sleep,/And miles to go before [we] sleep.

Shrugging, Hissing and Feeling Groovy

Andrew Eagle

|

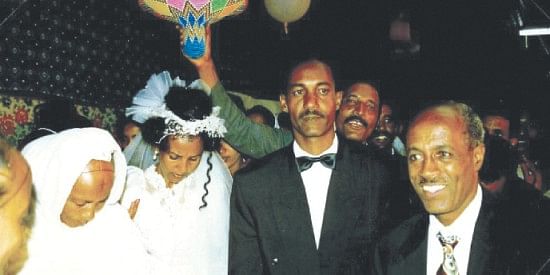

| The bride and groom at the 'Tent' reception. |

There are times travel itself plans a day off: days left open with not much to do between bus journey and plane booking. It was on such a day in January 1998 that I lazed over breakfast in one of those small side street cafés in the small Eritrean capital of Asmara, hoping to prolong the coffee as prelude to a day given to postcard writing and laundry.

Asmara, with a population of 500,000 people, is a pretty place set among small hills atop an escarpment some 2,325 metres above and 60 kilometres inland from the Red Sea. It has fine boulevards and admirable Italian architecture, for Eritrea was an Italian colony until 1941. There's a nifty craft market to explore and both the cathedral and mosque to visit, with the approximately five million Eritreans, speaking nine different languages between them, divided more or less equally between the two religions. Yet having stayed a few days, what else was there?

The Eritrean people were complex. They spoke of hardship, not least the challenges of poverty sadly familiar to many Bangladeshis; not least the legacy of Africa's longest war, thirty years, before successful secession from Ethiopia in 1993. Like Bangladeshis, Eritreans are rightfully proud of their independence. But the tensions they spoke of took place in an atmosphere that was incredibly and strangely laid back. Perhaps that is Africa.

Asmara Skyline

Was it the soft rustle of the Eritrean English accents or the easygoing manner of the people? Was it that old African lady who'd called out 'buon giorno' in Italian or facing that odd situation in small towns where beer was more readily available than water? It could have been watching camel traders pass on their way to market that slowed the rhythm. Whatever it was, despite the ongoing struggle of life, in Eritrea it was possible, even when on holidays, to feel like the least relaxed person in the country.

Casual as things were, it was hardly unusual for the guy at the next table in the café to start conversing. His name was Tewelde and he was pleased to know I was Australian. There was a famous Australian eye surgeon Dr Fred Hollows, renowned for treating cataracts amongst the poor and training local doctors. He was something of a legend in Eritrea and I'd met locals who'd said they could see because of him. It broke the ice.

'I'm going to a wedding this afternoon,' Tewelde said, 'would you like to come?'

In Australia weddings are expensive and exclusive, so despite my enormous curiosity I declined. Tewelde persisted. 'Don't worry,' he said, 'in Eritrea it's allowed to invite friends.' With the weakness of my curiosity and strength of his encouragement, I finally agreed. Goodbye postcards and laundry!

A few hours later we met, Tewelde now donning a sports jacket for the occasion, and set off for the church hall where the first reception was going on. Tewelde explained that in Asmara it was usual for Christian weddings to take place on Sundays in January, since it was the month following the traditional harvest season when people could afford weddings. People were already drinking, dancing and feeling groovy when we arrived. I wasn't allowed just to watch.

Asmara Street Scene.

It must have been quite a sight, my first Eritrean dance steps. I copied those around me, shrugging my shoulders and twisting to the heavy African beat, shuffling and hissing like a steam train in time with the music, the way they express their enjoyment of the music. The only concession was that unlike Latin American dancing for example, there was no need for the coordination of pre-rehearsed steps. In Africa all there was to do was open oneself to the music and let it guide your limbs, freestyle. My arms and legs moved in ways they'd never done before.

After a while we jumped in a car and followed the bridal party out to the plateau's edge, at a place where you could look down on the clouds in the direction of the Red Sea coast: a perfect location for wedding snaps.

Then it was time for the second reception, the one that runs into the deep night. Tewelde said they're normally held in large tents pitched across one of the capital's side alleys, and it being a Sunday in January I noticed several tents on the drive to reach ours.

Inside the floor was covered with straw; not sure why. Firstly we polished off a full dinner of spicy goat meat and salads; washed down with honey beer served in metal pots large enough to have grown flowers in. They called them glasses but they were big.

The local food in Eritrea features holey, rubbery bread called injera, a single flat piece large enough to spill over a dinner plate. Onto it would be put the meat dish; and with whoever was there you would share it, eating with the hand Bangladeshi style. Injera takes some getting used to because of its unique flavour.

During the meal children came crawling under the sides of the tent and tried to steal food. I felt sorry for them. The guys beside me were furious, yelling something in Tigrigna that clearly meant 'go away!' I was just about to stick up for them, to suggest perhaps we could spare a little food for the street kids, when one of the guests noticed my concern. 'Don't worry,' he said smiling, 'it's our tradition. At first they try to steal food and we pretend to be angry about it; later we invite them to eat.'

After dinner with tables cleared, the real dancing began. I can't say my shrugging and hissing improved, but with the abundance of honey beer I was certainly feeling groovy, and lost my shyness for it.

Mostly the men danced, but also some women; and while the bridal party were dressed western style, the other ladies wore exquisite loose white cotton, hooded dresses trimmed with colourful bands of African design. In women's fashion it might be hard to beat the sari, but those Eritrean ladies were elegant.

After several rounds one woman proceeded to give me her outer skirt, a part of her dress! I had no idea what it meant. I confess I held a secret fear if I took it maybe I would have to marry her! So I refused and she was really insulted. I understood soon enough, when all the other men dancing were being handed skirts from various ladies and wrapping them like lungee. It must have been quite an honour to have been offered first.

The Eritreans didn't mind my poor judgement and the shrugging, hissing and feeling groovy continued. A while later an old man, he can't have been a day under seventy, wiggled as best he could onto the dance floor, using his walking stick to help him, and came in my direction. Onto my sweaty forehead he stuck a one Nakfa note, the lowest denomination in local currency. It was another custom, a compliment for nice dancing, and a particular honour: elders are well-respected in Eritrea.

'Do you know what people are saying?' Tewelde asked at the night's end. Well obviously not. It was in Tigrigna. 'He dances just like an Eritrean, they're saying, he's western but he can dance!' I blame the honey beer.

I'd told Tewelde I was to attend another wedding in two weeks, that of my Sikh friend, up the road in Chandigarh. Tewelde shook his head, 'I don't know, you come here and after a week you're dancing like a local, and soon you'll be in India and be just like an Indian!' To be as the local: every traveller's dream! While the truth was nothing of the sort, it did happen that two weeks later there was a bit of wild punching in the air and a different sort of twisting. It's hard on the leg muscles that bhangra.

The following morning I'd decided to take a day trip to Adi Quala, a town on the edge of the plateau where I'd heard there was a grand view down into Ethiopia. The bus station was both the national capital's terminal and a dirt yard surrounded by a brick wall. I was finding the right bus when a guy called across the yard, 'did you like the wedding?'

I sometimes wonder what happened to that couple. I hope they are having a nice life; because from May 1998, just four months after the wedding, a border dispute led to a second war against Ethiopia, until 2000, which claimed 70,000 Eritrean and Ethiopian lives. The groom was an army man.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |