|

Neighbours

Pakistan on the Brink

Sajid Huq

Islamabad, according to many Pakistani friends, is a rather boring city. The city is modern, but built as an administrative capital, lags behind Lahore and Karachi in cultural activities, entertainment options and general urban hustle.

However, on July 1st, scenes from Islamabad hogged TV channels both national and international, as the world watched Islamic militants take hostage hundreds of women and children in the center of the city. Lal Masjid, one of Pakistan's largest seminaries had become a fortress in which were holed the hostages, masterminded by two brothers, Maulana Abdul Aziz and Abdul Rashid Ghazi, reportedly with the blessings and direction of one Ayman Al Zawahiri, of Al Qaeda fame.

The Islamist firebrands had decided to break with the Pakistani military government - their former allies - and called for an immediate establishment of an Islamic State, increasingly incensed by Musharraf's pandering to America's War on Terror.

Ten days into the hostage crisis, after negotiations had failed, commandos from the Pak Army's Special Services Group, along with hundreds of troops, stormed the complex. Abdul Rashid Ghazi was killed, along with 76 militants and 11 soldiers. However, this is according to official reports. Pakistani TV stations, newspapers, and blogs give estimates that are almost double.

Curiously, Abdul Rashid, titled “Ghazi” for his valiance in the Afghan war against the Soviets, foresaw this bloody end. The Lal Masjid crisis seems akin to a suicide mission. Intended to provoke the Pak Army into retaliation and set the ball rolling towards a larger catastrophe. “We have a firm belief in God that our blood will lead to a revolution…God willing, Islamic revolution will be the destiny of this nation,” Ghazi predicted. Meanwhile, General Musharraf urged the nation to stand up against the “terrorists out to destroy the country.”

Since then, what has ensued is utter mayhem.

Series of bomb attacks targeting mostly security forces has claimed a staggering 285 lives this month, at least 180 between July 14 and the time of this article's writing. The deadliest was on Thursday, July 19, in Hub, 50 Kms from Karachi, when a car bomber, apparently targeting a vehicle carrying Chinese workers rammed into a police vehicle, killing 30 people, 23 of them innocent bystanders.

But a possible civil war between the militants and Musharraf's army is not the only impediment to (the latter's?)his designs for a “true” democracy in Pakistan, promised in 1999, still undelivered. But a possible civil war between the militants and Musharraf's army is not the only impediment to (the latter's?)his designs for a “true” democracy in Pakistan, promised in 1999, still undelivered.

On July 20, the Pakistani Supreme Court stepped all over Musharraf's efforts to oust Chief Justice, Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. On May 9, the General had summoned the Chief Justice to Army headquarters and asked him to resign. He accused Chaudhry of using his position for personal gain. Enraged by Musharraf''s authoritarianism, hundreds of lawyers demonstrated against his assault on the judiciary's independence. A week later, riot police attacked protestors and news channels broadcast tragic images of barristers being beaten up.

By June, the demonstrations had united large sections of Pakistan's civil society, snow balled into a country-wide anti-Musharraf movement, demanding fair elections, a civilian government and respect for the Constitution. Not since the end of dictator Ayub Khan's regime in 1960 did a military government so thoroughly antagonise both the Pakistani Left and the Right.

Ayub Khan had declared martial law in 1958, paving the way for a series of military interventions following his. Army Chief Yahya Khan took over reigns in 1969. Zia-Ul Haq in 1977, and finally President Pervez Musharraf in 1999. An understanding of Pakistan's political-military history is essential to gauging the present developments and future possibilities. In fact, the story starts somewhere during the British Empire in India.

Roots of Many Lal Masjids

Legacies of the British Raj did much to configure the civil-military relations in Pakistan, created in its wake in 1947. After the Rebellion of 1857, much of the British Indian Army had come from the Punjab, now divided between India and Pakistan. Punjab representation in the British Indian Army were often as high as 25%, although its population was around 7%, especially during the World Wars when South Asian recruits fought many of Britain's wars.

A “martial caste” evolved in Punjab, where joining the British Indian Army became a direct route to prestige, financial success, and great post-retirement benefits. This legacy continued after the Empire's demise in 1947, and a newly independent Pakistan inherited a disproportionate amount of the British Indian Army.

The Pak Army became the guarantors of the state's security and freedom from India, and relatively successful campaigns in the Indo-Pak wars of 1948 and 1965 confirmed the army's sense of purpose and superiority. Army officers were often better educated than their civilian counterparts while the high ranking officers were thoroughly Westernised, professing a love for alcohol, polo, and British military journals. A distrust of and scorn for civilian leaders and politicians became commonplace in the barracks. According to Pakistani journalists, “bloody civilians” became a cherished phrase in army officers' vocabulary as they stepped outside the gates of the Military Academy in Kakool.

In this environment of strained civil-military relations, stepped in one Zia-Ul Huq. The Cold War was already underway. Pakistan had become an American ally because of its friendly relations with China, a potentially useful friend, or a dangerous foe. Meanwhile the Nixon-Kissinger administration in the United States had no time for either Indira Gandhi or India.

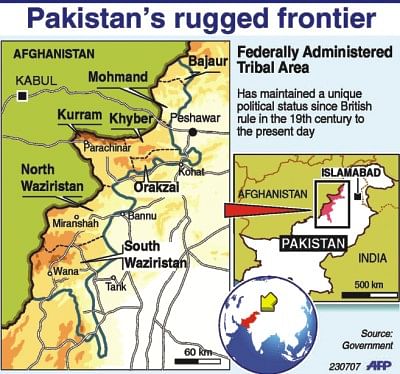

A landmark event was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. In ten years, the invading Red Army was summarily defeated by an alliance of the Afghan Mujahideen, thousands of jihadi recruits from Pakistan, others from the Arab Middle East, intelligence and military resources from General Zia's military government, with the blessings of the CIA.

Around this time, numbers of madrasas loyal to the cause of the Afghan mujahideen proliferated under the army's patronage. From 200-odd seminaries in 1947, there were 3000 by 1988. Much material support also went to firebrands like Maulana Abdullah, the man in charge of the Lal Masjid then. The Masjid received substantial land grants and attracted a large member of the military brass to its prayers. In 1984, it relocated to the posh E-7 sector of Islamabad.

Throughout the Afghan War, Lal Masjid operated as a factory that churned out fighters, a school, and a fund-manager for the mujahideen. Meanwhile, the Masjid and its leader, Maulana Abdullah stepped up their anti-Shi'a rhetoric - perhaps, an outcome of the increasing nexus between its clerics and Saudi Wahhabism. In 1998, Abdullah was shot dead by Shi'a assailants. But by this time, the Lal Masjid came to occupy an important niche in Pakistan's religio-political landscape. A seminary for young men, Jami'a Faridia had been a part of the mosque compound since its inception. Jami'a Hafsa was established for young women. The mosque establishment had also grown increasingly warm to the Taleban and allegedly, Al Qaeda in Afghanistan.

It was Abdullah's death that brought to power, his sons, Abdul Aziz and Abdul Rashid. The brothers continued where the father left off. Not unlike their Taleban allies, the brothers instituted a religious police that even included burqa-clad young women who went around threatening video-store owners, burning pornographic material, kidnapping prostitutes, and calling for an establishment of the Shariah. English-language dailies labeled them “Chicks with sticks.” Increasingly enraged by Musharraf's support for America's adventures in Afghanistan, Lal Masjid's students stepped up their anti-government activities.

The straw that broke the army's patience was the kidnapping of 22 Chinese masseuses in an upscale massage parlor in Islamabad by the burqa brigade. China and the US wrapped on Musharraf's shoulder. The government shut down the website of Lal Masjid and canceled their radio broadcast license. In retaliation, the brothers created the hostage situation.

A Foreboding Future

The Lal Masjid crisis is by no means a break from a recent history of religious militantism and extremism in Pakistan. It is important to understand these current problems in light of Cold War developments, and a nurturing of violent elements within the religious establishment that is at least as old as Zia's regime.

The outcome of these policies is manifest. Not only is the Army having to break its alliance with institutions such as the Lal Masjid, but last Saturday, July 21, the US government declared its intention to attack jihadi bases inside Pakistan, greatly worrying the Pak military government.

Meanwhile, there are scores of other reasons why Pakistani civil society is impatient to see the back of Musharraf. Since 2002, according to estimates, almost 600 Pakistani citizens have gone missing, picked up by law enforcement agencies, and ones that have been released have come forth with stories of great torture.

Opponents of the General also claim that Iftikhar Chaudhry, the reinstated Chief Justice, was suspended because he refused to do the General's bidding by blocking the sale of a state-owned steel mill, which would have contributedd to many officials' coffers. In general, reports of the Army's profiteering abound. In a recently published book on the Pak Army and its economic empire, political scientist Ayesha Siddiqa estimates that the military controls assets worth at least twenty billion dollars, a third of all heavy manufacturing in the country, and twelve million acres of land. As famous activist Asma Jahangir put it, “The Army is into every business in this country. Except hairdressing.”

It is clear that General Musharraf's days are numbered. How he will go is anyone's speculation. There are reports that the General is trying to strike a deal with Benazir Bhutto's Pakistan People's Party (PPP). Bhutto's government was not far from corruption and extortion itself, lest we forget. Pakistan was ranked three on Transparency Index's list of corrupt nations during her government, and her husband- widely known as “Mr 10%.”

But what worries Pakistani citizens and commentators more than extortion is that Musharraf handing over the reigns to Benazir hardly bodes well for religious extremism and violence in Pakistan. Whoever succeeds Musharraf will have no choice but to continue his recently adopted heavy-handed tactics in dealing with militants. PPP is of course, the largest socialist party, and as a political entity, greatly disliked by the religious right.

After 9/11, Bhutto had said to Fox News, “If I was prime minister, 9/11 wouldn't have happened.” She went on to argue that the Taleban would not have been strengthened if she were at the helm. Actions speak louder than words, and many fear that in Benazir's case, they won't. Jugnu Mohsin, publisher of the Friday Times, forbodes, “the fall of Musharraf could well lead to the rise of violent political Islam.”

Sajid Huq teaches at the New School and is a PhD candidate at Columbia University.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2007 |