Terror

in

the Name of God

Ahmede

Hussain

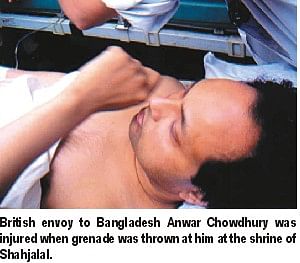

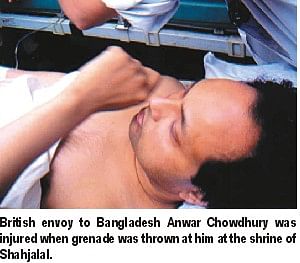

For

the Bangladeshi-born British envoy, Anwar Chowdhury, the

forenoon of May 21 started without any clue of what was

in the offing. It was 1:35 and a huge crowd of people

greeted Anwar, as he was about to leave the Shrine of

Shahjalal after saying Friday prayers. But as the envoy,

only 18 days into his new job, reached the exit door of

the 700-year-old tomb, a bearded man in his early forties

halted the High Commissioner's way. "The man was

telling Anwar to give him some money," recalls Advocate

Abdul Hai Khan, Anwar Chowdhury's grandfather and a witness

to the mayhem that would follow.

Khan

was helping the envoy out of the melee and he smelled

a rat when the man did not get out of their way after

repeated requests. "I grew suspicious. I looked up

at him; the man was well built and was wearing a fashionable

Comillar fatua," he says. This man cannot be a beggar,

Khan thought; so when the High Commissioner told Khan

to give the "beggar" 100 Taka, he said, "Just

look at him Anwar, this person is not at all a beggar."

Don't be so rude nana, Anwar replied. Khan, in turn, obliged

his grandson; the Sylhet-based lawyer reached down for

his purse and handed the beggar a hundred-Taka note.

Khan

was helping the envoy out of the melee and he smelled

a rat when the man did not get out of their way after

repeated requests. "I grew suspicious. I looked up

at him; the man was well built and was wearing a fashionable

Comillar fatua," he says. This man cannot be a beggar,

Khan thought; so when the High Commissioner told Khan

to give the "beggar" 100 Taka, he said, "Just

look at him Anwar, this person is not at all a beggar."

Don't be so rude nana, Anwar replied. Khan, in turn, obliged

his grandson; the Sylhet-based lawyer reached down for

his purse and handed the beggar a hundred-Taka note.

But

within seconds, a grenade was thrown at the British High

Commissioner; the bomb hit the parameter wall of the shrine

as he threw it up after it bumped on his lower abdomen.

"Anwar told me, 'Nana, save me; they have thrown

a bomb at us'," Khan recalls. "Within a few

seconds," he continues, "there was a huge bang;

we both fell on the pavement; and I saw blood rolling

on the ground from the High Commissioner's body."

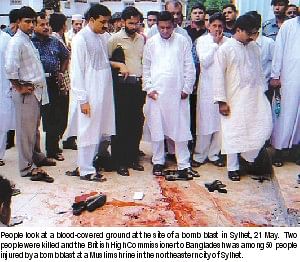

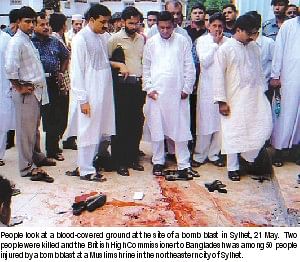

Though

no one has claimed responsibility for the attack; Advocate

Abdul Hai Khan believes it was not at all unexpected.

Only months ago, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) MP Delwar Hossain

Saiedi urged a gathering at the nearby Alyah Madrasah

field to resist what he called bedat (heretical

activities) in the shrine. Four days later, on January

12, a bomb was exploded at the shrine. The police arrested

24 people in connection to the blast; a probe body was

formed headed by the superintendent of the police. But

that committee's report has not yet seen the light of

the day despite repeated extensions of time. No progress

has also been made on nine other blasts that rocked the

north-eastern city since 1997 and have claimed 14 lives.

In

the last five years 140 have been killed and around 1,000

injured in several bomb blasts that ripped through different

public places across the country. Whoever the perpetrators

are, says security expert Brig-gen Shahedul Anam Khan,

the intention was to create panic and reap political dividend

of these blasts. Khan believes the subsequent governments'

failure to nab the culprits means, "either we are

not capable of doing it or the major political parties

do not want to see the culprits on the dock."

In

the last five years 140 have been killed and around 1,000

injured in several bomb blasts that ripped through different

public places across the country. Whoever the perpetrators

are, says security expert Brig-gen Shahedul Anam Khan,

the intention was to create panic and reap political dividend

of these blasts. Khan believes the subsequent governments'

failure to nab the culprits means, "either we are

not capable of doing it or the major political parties

do not want to see the culprits on the dock."

The

first such blast, in fact, took place in Jessore on March

6, 1999; the Awami League (AL), then at the helm, blamed

the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)-backed religious

zealots for the incident. Within two years, terror struck

at the heart of the capital on March 6, 1999; seven Communist

Party members died in simultaneous blasts at the Paltan

Maidan in Dhaka. Two more incidents of blasts jolted the

AL rule that ended in 2001. Though during its five-year-term

the AL government had failed to nab anyone for the blasts,

it could not resist guessing who the culprits were.

The

BNP, on the other hand, after coming to power, has been

religiously following the path of its predecessor; only

the other way around. The party has been denying the presence

of religious extremists from the very first blast by describing

it as a ploy to damage the country's image abroad. "Sometimes

it sounds as if the BNP has made a policy decision to

deny the link of the zealots to the blasts," says

Brig-Gen. Anam.

In

fact, the BNP-led government banned copies of Time magazine

and Far Eastern Economic Review for portraying Bangladesh

as a hotbed of religious extremism. The most publicised

case in this saga happened in 2002 when two British journalists

from Channel Four came to the country to make a documentary

on the presence of religious extremist outfits in the

country. Zaiba Naz Malik and Bruno Sorrentino were later

released after both of them, according to their lawyer

Ajmal Hossain, "Submitted statements expressing regret

for the situation arising since their arrival in Bangladesh."

The government, however, did not release Selim Samad and

Priscila Raj, who had been assisting them as translators.

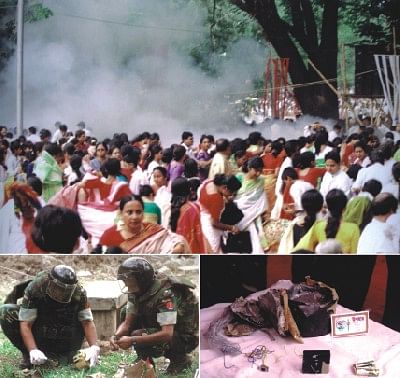

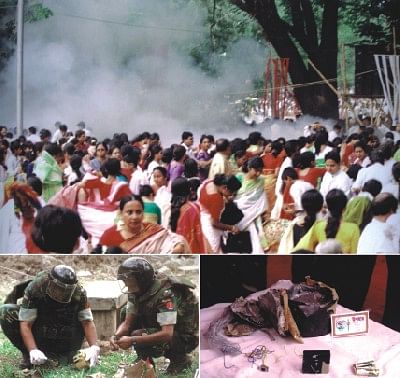

Panic-stricken

men, women and children run for cover (top) after the

huge explosion at the Ramna Batamul during Bangla New

Year celebrations that left nine killed and at least 20

others injured. After the gory incident, while law enforcement

and intelligence agencies collected remainder of the bomb

and other clues to the explosion (left), an army team

had to diffuse another bomb near the Baishakhi gate.

That

unwavering stand got a jolt within months when several

powerful bombs went off in four movie theatres in Mymensingh.

Within hours of the blasts, the prime minister, alluding

to the AL chief Sheikh Hasina, blamed those "Who

are making anti-Bangladesh campaign at home and abroad."

The PM's comment was followed by the arrest of three Bangladesh

Chatra League members; but the police was yet to arrest

anyone for the blasts.

"The

whole situation is really chaotic," says Brig-Gen

Shahedul Anam. "BNP denies the presence of religious

extremists on our soil because it needs the help of JI

and other religious parties to win elections. The AL,

on the other hand, are using the blasts as a pretext to

label the government as an adobe of religious bigotry,"

he continues. The situation can turn from sad to tragic

within months, he warns; "There is not any place

for religious bigotry and intolerance in the country;

but our failure to curb extremism may give birth to a

looming disaster," the retired army-man warns.

Bangladesh's

contribution to religious extremism dates back to the

era of Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. During the mid

and late eighties, hundreds of Bangladeshis went to the

country to fight for the Mujahidins against what they

considered the communist invasion of an Islamic country'.

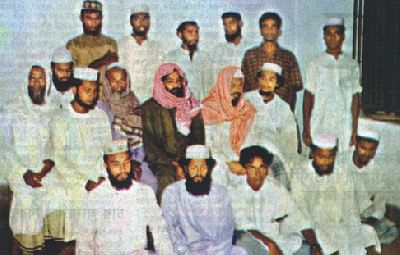

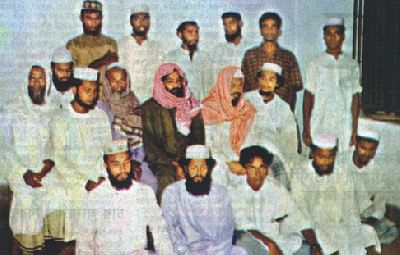

Maulana

Abdur Rauf, leader of Jamiatul Islamia, who was arrested

in Faridpur on September 19 last year with 17 accomplices,

told the police that, like him, about 500 Bangladeshis

went to Afghanistan to fight for the Jihadis, of them

33 died. Many have returned and with them have brought

extremism to a country, which has always prided itself

on its Sufi past.

In

fact, Jane's Intelligence Review (JIR) in its May 2002

issue says, "Osama bin Laden's February 23, 1998,

fatwa urging jihad against the US was co-signed by two

Egyptian clerics, an unidentified Pakistani and one named

Fazlur Rahman, leader of the Jihad Movement in Bangladesh

(JMB)." The JMB is not believed to be a separate

organisation, the JIR report continues, but a common name

for several groups in Bangladesh, of which Harkat ul Jihad

Islami Bangladesh (HJIB) is considered the biggest and

most important.

HJIB

came under spotlight when the group was charged with planting

two bombs at a meeting that was to be attended by the

then prime minister Sheikh Hasina. "The mission of

HJIB is to establish Islamic rule in Bangladesh,"

a US State Department report says. The group has an estimated

cadre strength of more than several thousand members,

and it operates and trains in at least six camps (in Bangladesh),

says the State Department, which has already listed the

HJIB as a terrorist organisation.

Maulana

Abdur Rauf who was arrested on September 19 last year

along with 17 accomplices told the police that about 500

Bangladeshis went to Afghanistan, of them 33 died.

Little

has been known about the group and its commander Shauqat

Osman, who is also known as Sheikh Farid. "Originally

the HJIB consisted of Bangladeshis who had fought as volunteers

in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan," the

JIR report says.

The

government remains conspicuously inactive when different

self-styled vigilante groups have been butchering innocent

people in the name of Islam across the country. The police

have yet to nab any of the members of the so-called Jagrata

Muslim Janata Bangladesh (JMJB), which have unleashed

a reign of terror in the southern districts.

Though

the prime minister has ordered the arrest of Bangla Bhai,

the so-called operations commander of the militant outfit,

newspaper reports suggest otherwise. "Two police

officers tipped off Bangla bhai who holed up in an outlying

village in Raninagar (in Naogaon district) where he set

up a vigilante camp to launch 'anti-outlaw drives',"

a Daily Star report says.

The

government is yet to ban the group even after local dailies

have run stories linking the JMJB with Osama bin Laden's

Al-Qaeda. This indifference, coupled with sheer arrogance

and political myopia, leading the country to an impending

disaster.

Khan

was helping the envoy out of the melee and he smelled

a rat when the man did not get out of their way after

repeated requests. "I grew suspicious. I looked up

at him; the man was well built and was wearing a fashionable

Comillar fatua," he says. This man cannot be a beggar,

Khan thought; so when the High Commissioner told Khan

to give the "beggar" 100 Taka, he said, "Just

look at him Anwar, this person is not at all a beggar."

Don't be so rude nana, Anwar replied. Khan, in turn, obliged

his grandson; the Sylhet-based lawyer reached down for

his purse and handed the beggar a hundred-Taka note.

Khan

was helping the envoy out of the melee and he smelled

a rat when the man did not get out of their way after

repeated requests. "I grew suspicious. I looked up

at him; the man was well built and was wearing a fashionable

Comillar fatua," he says. This man cannot be a beggar,

Khan thought; so when the High Commissioner told Khan

to give the "beggar" 100 Taka, he said, "Just

look at him Anwar, this person is not at all a beggar."

Don't be so rude nana, Anwar replied. Khan, in turn, obliged

his grandson; the Sylhet-based lawyer reached down for

his purse and handed the beggar a hundred-Taka note. In

the last five years 140 have been killed and around 1,000

injured in several bomb blasts that ripped through different

public places across the country. Whoever the perpetrators

are, says security expert Brig-gen Shahedul Anam Khan,

the intention was to create panic and reap political dividend

of these blasts. Khan believes the subsequent governments'

failure to nab the culprits means, "either we are

not capable of doing it or the major political parties

do not want to see the culprits on the dock."

In

the last five years 140 have been killed and around 1,000

injured in several bomb blasts that ripped through different

public places across the country. Whoever the perpetrators

are, says security expert Brig-gen Shahedul Anam Khan,

the intention was to create panic and reap political dividend

of these blasts. Khan believes the subsequent governments'

failure to nab the culprits means, "either we are

not capable of doing it or the major political parties

do not want to see the culprits on the dock."