Judgment Review

ITLOS Judgement: A Clear Legal victory for Bangladesh

Dr. Abdullah Al Faruque

|

Photo: burma.irrawaddy |

In the last month, the Hamburg based the Law of the Sea Tribunal delivered a historical judgment on delimitation of maritime boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar. A case first of its kind before the tribunal marked a distinctive and definitive legal achievement for Bangladesh. The dispute involved the delimitation of the territorial waters, exclusive economic zones and continental shelves of Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal. The judgment also marks an important precedent that will be pertinent for resolving future maritime boundary disputes. However, recent newspaper write up on the judgment in the newspaper have generated a considerable debate as some commentators have took the position that both countries have gained from the judgment and cast doubt on actual legal achievement of Bangladesh. This write up is a response to skeptics and asserts that Bangladesh has clearly won the case on the most substantial issues of the dispute. First, judgment is a clear legal victory for Bangladesh as its lawful claim on maritime zone has been recognized by the tribunal, which was previously disputed. Second, long-standing dispute between two countries has been resolved peacefully. Bangladesh always tried to settle the problem through bilateral negotiation. But Myanmar was reluctant to settle it by bilateral negotiation or even by international tribunal. Failing to reach an agreement through negotiations, Bangladesh went for judicial means of settlement of dispute by neutral third party. Amicable and peaceful settlement of the dispute is itself a legal victory for Bangladesh. Third, a settled and demarcated maritime zone will definitely pave the way to Bangladesh to gain access to mineral resources in maritime zone peacefully, which will accelerate its economic development. But a long-standing dispute over maritime boundary delimitation with India and Myanmar remained a major stumbling block to exploration of these resources. Bangladesh has been deprived of her legitimate claim over maritime resources for a long time due to the uncertainty created by the absence of an agreed boundary. When there is no agreed boundary, exploration for hydrocarbon reserves can be delayed throughout a considerable area in and around the disputed maritime zones. The overlapping claims of the disputing states necessitated peaceful settlement for exploration of mineral resources in the demarcated maritime zone. The Bay of Bengal has become very important for hydrocarbon reserve, especially after India's discovery of 100 trillion cubic feet (tcf ) of gas in 20052006 and Myanmar's discovery of 7 tcf gas at the same time. It should be mentioned that when Bangladesh declared its 28 offshore blocks in Bay of Bengal in 2008, and invited bidders to explore in the blocks, both Myanmar and India opposed vehemently to Bangladesh initiatives and as a result, most of the international oil companies stayed away from the bidding. Now oil companies can participate in the bidding process for all blocks except four without any controversy after the ITLOS judgment.

Now let me elaborate more on the specific aspects of dispute which involves many complex legal issues for delimitation.

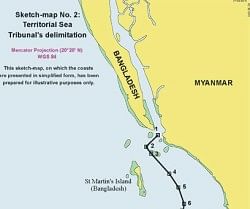

First, the Tribunal applied the equidistance principle in delimitation of territorial waters and recognized that Bangladesh has the right to a 12 nm territorial sea around St. Martin's Island. In this regard, Myanmar has raised the issue of St. Martin's Island as a special circumstance in the context of the delimitation of the territorial sea and argued that the St. Martin's Island should be totally ignored in such maritime formation. But the Tribunal observed that the Island is situated within the 12 nm territorial sea limit from Bangladesh's mainland coast and concluded that the island should be given full effect in drawing the delimitation line of the territorial sea between the Parties.

Second, regarding the issue of relevant coasts in determining delimitation of maritime zones, Bangladesh argued that its entire coast is relevant. Myanmar opposed this argument. The Tribunal rejected the claim of Myanmar and concluded that the whole of the coast of Bangladesh is relevant for delimitation purposes.

Third, Myanmar demanded the application of the equidistance principle for delimitation, while Bangladesh always sought to delimitate its maritime boundary on the basis of the application of the equitable principle. It was anticipated that the delimitation of the maritime boundary on the basis of the equidistance principle would result in the annexation of much of the sea area of Bangladesh by Myanmar. Bangladesh would get only tiny share in Bay of Bengal and it would be virtually cut-off from accessing high sea if it was delimited on equidistance principle. The Tribunal applied the equitable principle instead of equidistance to solve the dispute. The Tribunal recognized that each delimitation problem involves a situation that has its own unique characteristics to be taken into account. Special circumstances of coastal geography have a fundamental role in arriving at an equitable solution of maritime delimitation problems. Bangladesh has a concave coast. Countries with concave coasts require unconventional solutions. Another factor is that a boundary line should not be drawn in such a way that encroaches on or cuts off areas that more naturally belong to one party than the other. Bangladesh's mostly adjacent rather than opposite location of maritime borders, together with the concave, unstable and broken nature of her coastline- all these special circumstances and relevant factors support the basis of the claim of Bangladesh for the delimitation of maritime boundaries on the equitable principle. Bangladesh argued that delimitation of exclusive economic zone, continental shelf and area beyond 200 nm should be based on equitable principle. In particular, Bangladesh states that Myanmar's claimed equidistance line is inequitable because of the cut-off effect it produces. On this point, the Tribunal observed that the goal of achieving an equitable result must be the paramount consideration guiding the delimitation. In this regard, the Tribunal adopted a three-stage approach: at the first stage it constructed a provisional equidistance line, based on the geography of the Parties' coasts and mathematical calculations.

At the second stage, after drawing the provisional equidistance line, it has made an adjustment so that the line produces an equitable result. At the third and final stage in this process the Tribunal has considered that the adjusted line should not result in any significant disproportion between the ratio of the respective coastal lengths and the ratio of the relevant maritime areas allocated to each Party. In adjusting provisional line, the Tribunal has considered relevant circumstances with a view to achieving an equitable solution. At this point, Bangladesh highlighted three main geographical and geological features as relevant circumstances such the “concave shape of Bangladesh's coastline”, location of St. Martin's Island and the Bengal depositional system as a proof of natural prolongation of the landmass of Bangladesh. Myanmar contended that there does not exist any relevant circumstance that may lead to an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. But the Tribunal observed that the coast of Bangladesh is manifestly concave.

The Tribunal further noted that, on account of the concavity of the coast in question, the provisional equidistance line it constructed produces a cut-off effect on the maritime projection of Bangladesh. Therefore, the Tribunal adjusted the line to achieve an equitable solution. However, the Tribunal did not consider St. Martin's Island and the Bengal depositional system as relevant circumstances.

Fourth, Bangladesh claimed that the Tribunal has jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 nm. But Myanmar objected that the Tribunal has no such jurisdiction to do so. But the Tribunal found that it has jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 nm.

Fifth, Myanmar's argument that Bangladesh's continental shelf cannot extend beyond 200 nm was rejected by the Tribunal. The tribunal also rejected similar claim of Bangladesh that Myanmar's continental shelf can not extend beyond 200 nm.

Finally, the Tribunal recognized that Bangladesh has maritime zone up to 200 nm from baseline and has also an entitlement to the continental shelf beyond 200 nm. On the other hand, it also rejected Bangladesh's claim that Myanmar enjoys no such entitlement beyond 200 nm. The Tribunal has recognized that both Bangladesh and Myanmar have entitlements to a continental shelf extending beyond 200 nm. The Tribunal observed that the concavity of the Bangladesh coast will also be a relevant circumstance for the purpose of delimiting the continental shelf even beyond 200 nm.

Thus, in terms of more specific points of judgment, it can be gleaned that although the ITLOS has rejected some of the arguments of Bangladesh, such rejection did not affect substantially what Bangladesh wanted from the judgment. In fact, Bangladesh has got a greater share in Bay of Bengal through the judgment, which was not otherwise possible through bilateral negotiation. This judgement will undoubtedly have great persuasive value in the resolution of dispute between Bangladesh and India on maritime delimitation, which is currently pending before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague of Netherlands.

The author is Professor, Department of Law, University of Chittagong.