Human Rights advocacy

Domestic violence cases

State obligation to act with due diligence

Shafiqur Rahman Khan

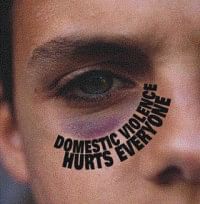

Domestic violence is one of the biggest human rights violations that affect women all over the world regardless of their color, nationality, or age. This problem has reached such a degree that women appear to be more at risk of facing violence inside of the home by a husband or partner, than outside by strangers. However, the traditional view that the State cannot be held responsible for acts of violence inflicted by private actors has been the major impediment to the implementation of legislation that seeks to protect women from such violence. This writing aims to challenge this view and examines the legal reasoning which demonstrates that the responsibility to protect women from domestic violence lies with the State itself.

Domestic violence is one of the biggest human rights violations that affect women all over the world regardless of their color, nationality, or age. This problem has reached such a degree that women appear to be more at risk of facing violence inside of the home by a husband or partner, than outside by strangers. However, the traditional view that the State cannot be held responsible for acts of violence inflicted by private actors has been the major impediment to the implementation of legislation that seeks to protect women from such violence. This writing aims to challenge this view and examines the legal reasoning which demonstrates that the responsibility to protect women from domestic violence lies with the State itself.

Legal nature of domestic violence against women

- When? Every day

- Who? Women throughout the world

- What? Face violence

- Where? In the home

- Why? Generally, because governments and the community ignore their responsibility to prevent this violence.

This briefly gives a simple description of the worldwide problem of domestic violence faced by women from all nationalities, cultures and races. Violence against women is not only restricted to violence inflicted by strangers. Indeed, women are more often at risk of facing violence perpetrated by those with whom they live. In fact, women are frequently battered, sexually abused and psychologically injured by persons with whom they should enjoy the closest trust.

Domestic violence is a pattern of behavior that may include physical, emotional, economic and sexual violence; its purpose is to establish power and control over an intimate partner, such as the wife or girlfriend, through fear and intimidation. Unfortunately, as it has been noted in the article of Andrew Byrnes, “this maltreatment has gone largely unpunished, unremarked and has even been tacitly, if not explicitly, condoned.” The failure to investigate and expose the true extent of violence allows governments and the community more generally to ignore their responsibilities.

Domestic violence poses a dilemma not only in law but in the human psyche as well: inherent in domestic violence is the dichotomy between love and hate. It is within the boundaries of an ostensibly loving relationship that violence manifests itself. Moreover, home is often associated to security, comfort, protection and love. It is the belief that home is automatically a safe place that is invoked as a common justification to deny the huge domestic violence problem that women are facing. The 'cynical' side of domestic violence is the fact that it usually takes place in secret and the sufferings of the victims happen in silence. The psychological consequences of domestic violence can even be more harmful than the physical pain itself: it can really destroy a woman's self-esteem, confidence and the capacity for resistance, because domestic violence is degrading and humiliating. It can push the battered woman to live under the black cloud of constant terror and shame. It can obliterate the personality in such a way that it becomes a serious assault on human dignity which is a core concept of human rights law. Domestic violence dehumanises women, it can reduce them to passivity and submission. In this context, it is at home that the application of human rights should begin.

General Recommendation No. 12 of the CEDAW Committee requires States to give statistical information on violence against women. Not all acts of violence against women are reported, and this makes it hard to get clear statistics regarding the number of women subject to violence. However, statistical work reveals that the number of gender-based violence victims exceeds victims of war. It is only very recently that few NGOs of Bangladesh had statistics regarding domestic violence against women but, still no official statistics has been produced or made in public. The lack of data at the national level has been a big obstacle for the development of policies, strategies and programs in this field. The numbers (published by NGOs) are shocking and reveal the grim reality of violence against women happening behind closed doors.

On the general basis, it can be noticed that violence by husbands is the most common form of violence in the lives of married women, much more than assault by strangers and acquaintances. The research also reveals that women who have been exposed to physical violence often have experienced this violence in severe levels. Furthermore, it shows that violence against women is mostly a hidden problem, because half of the women experiencing violence had not talked about it with anybody before being interviewed in the context of the statistical research. This shows that domestic violence is one of the most common crimes, but it is also one of the most hidden ones. Besides, women very rarely seek help from health institutions, police or other support services. Education is also not a concrete indicator. Three out of ten women who have a high school or higher education have been exposed to physical violence by their husbands or partners. This shows that domestic violence is a problem for women regardless of their level of education.

Regardless of location or women's education, violence against women remains a worldwide problem, but it is difficult to assess a global statistical data. The WHO website indicates that between 15 percent and 71 percent of women reported physical or sexual abuse. This number does not seem to be very meaningful, because the margin between the percentage numbers is quite wide. However, the universality of the problem of domestic violence can be proved by the fact that it is also a problem in developed countries, such as Sweden, which is one of the human rights champions. The National Survey conducted by the Swedish Government (published in 2001) reveals a shockingly high prevalence of violence against women.

State obligation

- Who? States

- Where? Throughout the world

- What? Should remedy to domestic violence

- Why? Because it is urgent

- When? Now!

This simplistic way of questioning emphasises that the responsibility to ensure accountability and to guard against impunity lies with the State, not with the victim. For Bangladesh, as for many other countries, women's rights are not given priority. It is with the pressure of different human rights instruments, the CEDAW monitoring process and women's rights organisations that national legislative changes have been realised.

The advocacy against domestic violence can be based on numerous human rights treaties, both general and specific to women's rights. However, the lack of a special convention on violence against women remains a problem. In the Inter-American system, the Convention 'Belem do Para' on the eradication of violence against women specifically details state obligations in respect of domestic violence. The Council of Europe has not yet adopted any human rights instrument affirming and elaborating on the human rights of women.

The issue of domestic violence needs to be taken seriously and treated in its context rather than as an isolated problem detached from its causes and consequences for human rights of women. It should be analysed and evaluated in the context of gender inequality and also torture or inhuman and degrading treatment in order to underscore its gravity.

Furthermore, domestic violence is a time consuming issue and it cannot be solved in one day due to the various deeply rooted challenges that impede the development of women's rights. The economic and social disparities between men and women constitute a major obstacle that should be overcome in the light of the understanding that without the full implementation of economic and social rights, the civil and political rights will keep being an illusion.

At the national level, cultural myths have a negative impact regarding the eradication of the problem. In that regard, the CEDAW process does important cultural work since it encourages States to adopt the international women rights standards and to undertake effective measures aiming the effective implementation of the norms.

Also, there is no question that the crimes of domestic violence are often more complex and more difficult than other crimes, because they happen in silence behind closed doors. This should demand greater diligence by the authorities, rather than less. The traditional dichotomisation between the private and public spheres should be eradicated both regarding the legislation and the attitudes of the police and judges.

Reflecting thoughts

It should finally be accepted that the state inaction regarding domestic violence, its refusal to deal with the problem seriously and its reluctance to prosecute and punish male perpetrators fosters the victimisation of women. States like Bangladesh should therefore act with exemplary due diligence with respect to the prevention, protection, punishment and reparation of such acts. For the case of Bangladesh, the recent legislative changes and the different campaigns that have been initiated prove that the State is willing to make efforts with the purpose of eliminating domestic violence from the quotidian life of women in general. But the major difficulty comes from the fact that domestic violence is one of the numerous human rights violations that Bangladesh has to solve.

The writer is a Faculty Member of the Department of Law, Jagannath University, Dhaka. Dhaka.